Bionic pig penises offer a "promising" new erectile dysfunction treatment

Can we get some morning hydrogel?

We can rebuild the human penis. We have the technology. Whether we can make the organ of many an insult, joke, or admiration better, stronger, or faster is another thing entirely, one may argue. But modern science is coming up with yet more ways to fix the ol’ pecker when it can’t… well, peck.

In a study published Wednesday in the journal Matter, researchers in China developed an artificial material that mimics a connective tissue, the tunica albuginea, responsible for keeping the penis erect during sexual arousal. When placed into pig penises with tunica albuginea injuries, the innovative material was able to restore erectile function. It could eventually do the same in humans with an injured or impaired tunica albuginea due to conditions like Peyronie’s disease. It could also one day help repair other organs, like the heart and bladder.

“The study shows that the artificial biomaterial created can adequately repair these defects, with good outcomes short term,” Anthony Atala, a pediatric urologist and director of the Wake Forest Institute For Regenerative Medicine, tells Inverse. “The technology is promising and warrants further investigation so that it can someday be safely transitioned to human patients who can benefit from this advance.”

Atala was not involved in the new study.

“The greatest advantage of the [artificial tunica albuginea] we report is that it achieves tissue-like functions by mimicking the microstructure of natural tissues.”

Here’s the background – Here’s a rundown of penis anatomy (in case you missed out on it in sex ed).

Contrary to what it feels like when excited, the human penis does not have a bone, although penis bones do exist within the animal kingdom. Rather, the male sexual organ is comprised of three spongy cylinders — a paired corpora cavernosa, which runs side-by-side down the length of the shaft, and a single corpus spongiosum that runs from base to tip. All three spongy structures fill with blood when aroused, but by themselves, aren’t capable of erection. That’s where the tunica albuginea comes in.

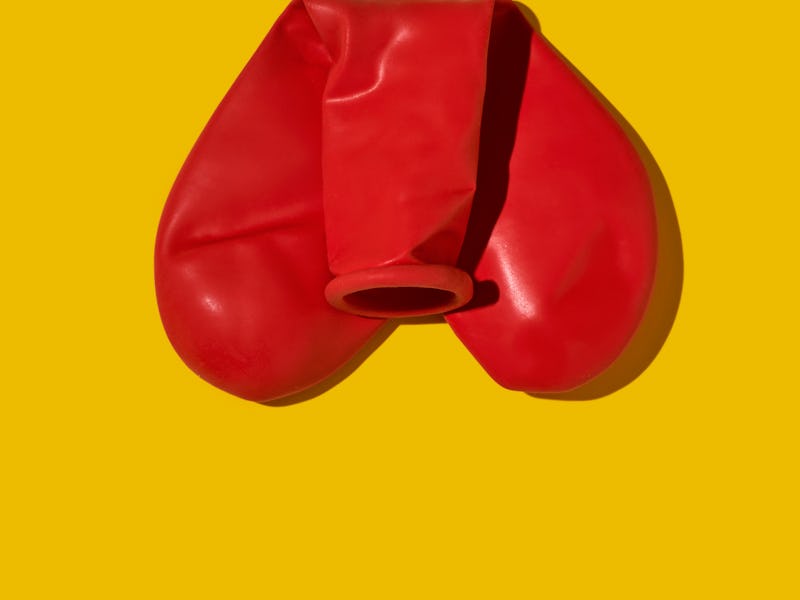

Wrapping all the way around, the tunica albuginea forms a thick sheath made of densely packed, highly organized collagen and elastin fibers. Its role is to keep the blood in the penis’ other spongy structures from escaping back into the main circulation much like pinching the neck of a balloon to keep the air in. Now, the tunica albuginea has some incredible tensile strength estimated at a maximum of 1500 millimeters mercury or 29 pounds per square inch (PSI), just at the lower end of the ballpark recommended for a car tire. But above this limit, the tunica albuginea can tear, resulting in what’s called a penile fracture.

Aside from trauma, the tunica albuginea can also weaken with age or harden, as seen in Peyronie’s disease, an inflammatory condition affecting up to 23 percent of middle-aged and older males where plaques of scar tissue curve the penis abnormally and make sex often very painful.

Urologist Atala says defects with the tunica albuginea are challenging to repair, both in terms of physical deformities and sexual function. In the case of Peyronie’s disease, there’s only one FDA-approved drug called Xiaflex, an injection that chemically breaks up the plaques. Other options include cutting out the scar tissue from the tunica albuginea and replacing it with a tissue graft as well as penile implants.

Some 23 percent of middle-aged and older males experience Peyronie’s disease, which causes the tunica albuginea to weaken.

How they did it — Motivated to create a material that could somehow replicate the biomechanical properties of the tunica albuginea and better restore erectile function, Xuetao Shi, a professor of tissue engineering at the South China University of Technology, developed a hydrogel-based artificial tunica albuginea.

“The greatest advantage of the [artificial tunica albuginea] we report is that it achieves tissue-like functions by mimicking the microstructure of natural tissues,” he says in a press release.

Shi and his fellow researchers accomplished this feat of bioengineering using a material called polyvinyl alcohol that’s found in a variety of commercial products (and also in dry eye-relieving eye drops). When fabricated into small patches, it boasts a curled fiber structure on par to how collagen and elastin fibers in the penile connective tissue straighten and stretch all the while absorbing strain.

After determining the hydrogel wasn’t toxic or harmful to living cells or blood (since it’s meant to be long-term in the body), Shi and his colleagues tested it out in healthy male miniature pigs, albeit with damaged tunica albugineas. Twelve mini-pigs known as Bama pigs (yes, it’s a real breed, and they’re pretty darn cute) were divided into three groups — one control with no treatment, one that got the hydrogel, and another that got a suture surgery. The small artificial tunica albuginea patches were inserted into the porcine penises, swapping out the damaged bits.

Much to the researchers’ surprise, these Bama pigs “regained normal erection immediately after the use of [the artificial tunica albuginea],” says Shi, which was comparable to a typical pig penis.

But the success came with a caveat. One month after grafting the bionic tissue, the researchers sacrificed the pigs to see if the hydrogel was able to restore the normal structure of the connective tissue’s collagen and elastin fibers. That didn’t appear to be the case — scarring had developed, which isn’t unexpected. But the scarring was no different from scarring seen in typical penile tissue, and the treated pig penises still managed to become erect when injected with saline.

“The results one month after the procedure showed that the [artificial tunica albuginea] group achieved good, though not perfect, repair results,” said Shi.

“The next stage will be to consider... the construction of an artificial penis from a holistic perspective.”

What’s next — There are tons more experimenting to be done before crossing over to humans, and there’s the potential of repairing more than just penises but load-bearing soft tissues such as blood vessels, intestines, tendons, the bladder, and the heart.

Shi and his colleagues believe this technology could inspire electronic skins, wearable devices, implantable sensors, and even soft, flesh-like robots.

“Our work at this stage focuses on the repair of a single tissue in the penis, and the next stage will be to consider the repair of the overall penile defect or the construction of an artificial penis from a holistic perspective,” explained Shi in the statement.