In a first, astronomers catch the Solar System moving through space

Our Sun has a new address.

The Gaia spacecraft hovers in space, 1.5 million kilometers from Earth. In its lonely spot, it spins on itself to scan the cosmos and map the surrounding stars.

On Thursday, an international team of astronomers released Gaia's most precise data on nearly 2 billion of these fiery orbs, offering unprecedented insight into how stars, including our Sun, move through the Milky Way over time.

Their findings mark the first time scientists have seen this kind of transition in action — and make a major update to the map of the Milky Way.

The European Space Agency (ESA) launched the Gaia space observatory in 2013 to survey the Milky Way's stars. Since then, the spacecraft has measured the position and motion of stars in our galaxy and some stars in small neighboring galaxies multiple times. It has enough fuel to continue on its mission until 2025.

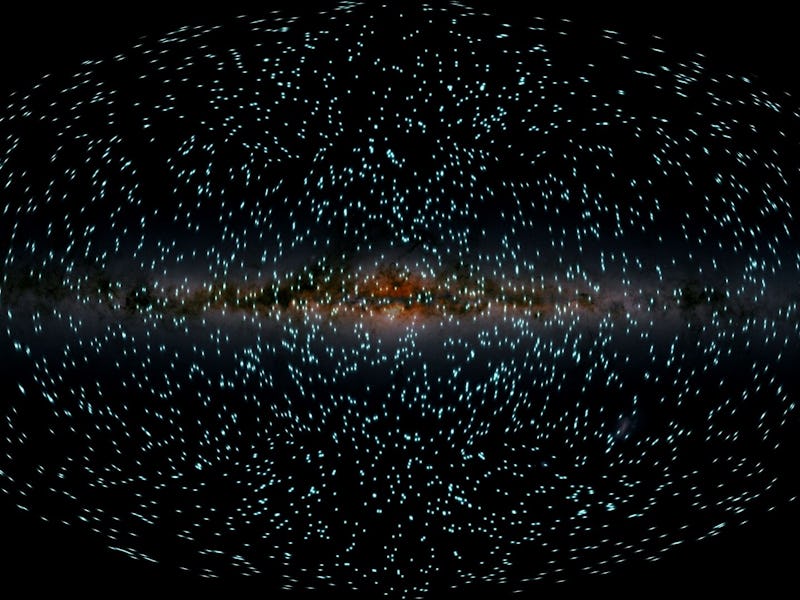

This illustration shows how 40,000 stars in the Milky Way will move across the sky in the next 400,000 years

"The stars are one of those things that have fascinated people from the very beginning of human intelligence," Gerry Gilmore, a professor at the Institute of Astronomy at Cambridge University and a member of the team of scientists behind the new work, tells Inverse.

"People have wondered: 'What are those bright lights that come out at night, where are they in the universe, and where did they come from.'"

This is Gaia's third dataset release; the two previous releases were issued in the years 2016 and 2018. This is the most precise one thus far, compiled over three years and consisting of 1.3 terabytes of data — some 2.4 times the size of the last dataset.

The data were presented Thursday at a special meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The new dataset includes the most-accurate measurements of 300,000 stars located within 326 light years of the Sun ever made, as well as the stars in the Milky Way's two closest neighbors — the Small and Large Magellanic Clouds.

Gaia's view of the Milky Way's neighboring galaxies.

Gaia’s measurement of the distances between stars are 50 percent more accurate than in previous datasets, and measurements of each star's velocity is 100 percent better, according to the researchers.

Stellar motion — One of the things Gaia reveals, however, is not contained in any single dataset. Rather, across this new release and previous datasets, scientists can track the motion of stars across the Milky Way.

Stars and other objects in the universe are constantly in motion due to gravity, which pushes them around the center of their galaxy.

Our own Solar System has been moving around the Milky Way for billions of years, changing its position in the galaxy. As a result of the Milky Way's gravitational pull, the Solar System accelerates by 7 millimeters per second each year in its orbit around the galaxy.

But this is the first time scientists have ever seen the Solar System's motion in action.

"We've known that it is moving, but we didn't expect to see it already," Gilmore says.

"We drifted out from the inner regions to the suburbs of the galaxy," he says.

Our changing skies — Gaia also measures the changing brightness and positions of the stars over time — and how fast they are moving towards or away from the Sun.

From these data, researchers can start to predict what Earth’s night sky will look like over the next 1.6 million years.

As stars continue to move around the galaxy, all the constellations we have grown familiar with in the night sky will eventually disappear and our view of the cosmos will change. Further research is needed to work out when and how each constellation will shift, however.

More information to this end could come in the next Gaia release. The team behind the observatory plans to put out a more updated dataset in the year 2022. The new data could reveal exoplanets orbiting around stars in the Milky Way.

For this dataset, scientists will measure the gravitational effect caused by planets on their host stars, such as the one imposed by our Solar System's giants Jupiter and Neptune which causes the Sun to slightly wobble.

These small effects can reveal others stars with planetary bodies orbiting around them. Ultimately, the scientists want to discover why some stars have planets, and others do not.

This article was originally published on