Look! Astrophysicists Spotted A Supermassive Black Hole Slowly Starving a Galaxy to Death

The snapshot is a celestial crime scene photo.

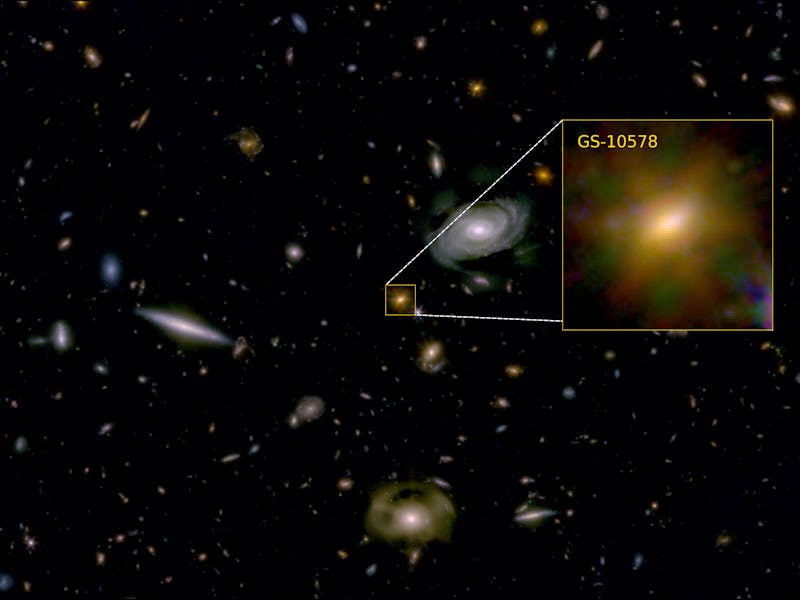

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) recently helped solve a cosmic “murder,” the untimely demise of Pablo’s Galaxy, more formally known as GS-10578: a disc-shaped galaxy about the size of our Milky Way. Its time of death? Just 2 billion years after the Big Bang.

Light from this distant galaxy had to begin its trip across the cosmos about 2 billion years after the Big Bang in order to reach Earth, giving us a snapshot of the early universe. But the snapshot that reached us is basically a celestial crime scene photo, because in galactic terms, Pablo’s Galaxy is dead, meaning that it’s stopped forming new stars. Using JWST’s instruments, Cambridge University astrophysicist Francesco d’Eugenio and his colleagues caught a supermassive black hole red-handed, slowly starving the galaxy to death.

“We found the culprit: the black hole is killing this galaxy,” says d’Eugenio, who led the recent study, in a statement. He and his colleagues published their work in the journal Nature Astronomy.

This deep-field view from JWST includes GS-10578, nicknamed Pablo’s Galaxy.

An Astrophysical Whodunit

D’Eugenio and his colleagues used JWST’s sensitive infrared instruments to spot something other investigators missed: dense streams of cold gas rushing away from the galaxy. The supermassive black hole lurking at the heart of Pablo’s Galaxy is flinging the gas — which would otherwise be the raw material for billions of new stars — out into space at more than 2 million miles per hour. Without dense clouds of interstellar gas, the galaxy can’t form new stars, which means that once the stars now lighting up Pablo’s Galaxy eventually burn out in a few billion years, it’ll be good night forever.

Based on d’Eugenio and his colleagues’ calculations, the black hole is hurling more material into space than the galaxy needs in order to survive. Previous studies noticed that Pablo’s Galaxy was dying, but they spotted only faint wisps of warm gas flowing away from the galaxy’s center. Those much smaller streams of gas weren’t enough of a loss to explain why the galaxy had stopped forming new stars. But when d’Eugenio and his colleagues looked at Pablo’s Galaxy with JWST’s instruments, they realized that the galaxy is basically hemorrhaging interstellar gas. It’s bleeding out, and it’s happening fast.

“If it had enough time to get to this massive size [by the time the universe was just 2 billion years old]. Whatever process that stopped star formation likely happened relatively quickly,” says Cambridge University astrophysicist Roberto Maiolino, a coauthor of the recent study, in a statement. “In the early universe, most galaxies are forming lots of stars, so it’s interesting to see such a massive dead galaxy at this period in time.”

It turns out that most of the gas streaming away from Pablo’s Galaxy is so cold that it doesn’t emit light, or even much heat. Astronomers needed JWST’s very sensitive instruments to detect the very faint infrared radiation coming from the gas streams — and to notice that those streams were blocking some of the light from the stars behind them.

The gas is being accelerated to more than 2 million miles per hour, fast enough to escape the strong pull of the galaxy’s gravity, by the supermassive black hole at the center of Pablo’s Galaxy.

Black holes are notoriously messy eaters; another recent study found that a supermassive black hole in the center of the Circinus Galaxy (just a million light years away from Earth) only “eats” about 3 percent of the gas that gets pulled into the disc of material spiraling inward around the black hole. The rest gets shoved away violently at a fraction of the speed of light. Particles falling into the black hole are moving so fast that they release tremendous energy when they finally tip past the event horizon, and the pressure from that radiation can push gas in its path hard enough to accelerate it to ridiculous speeds.

Other studies have shown that messily-feeding supermassive black holes can disrupt star formation in their host galaxies. But while models have predicted that a sufficiently sloppy black hole could, in theory, totally shut down its galaxy’s ability to make new stars for good, this is the first time astronomers have seen it happen.

D’Eugenio and his colleagues plan to take another look at Pablo’s Galaxy with the Atacama Large Millimeter/ submillimeter Array, a flock of microwave antenna high in the Atacama Desert of Chile. ALMA can peer into distant galaxies in even longer wavelengths of light than JWST. That means it will enable astronomers to see out the darkest, coldest patches of gas in Pablo’s galaxy, to see where fuel for star formation might still be tucked away, out of the supermassive black hole’s murderous reach.