“Rubble pile” asteroids may be surprisingly hard to destroy — study

When Japan's Hayabusa mission traveled to asteroid Itokawa, it collected samples. These successfully reached Earth in 2010.

Asteroids come in a broad range of sizes and sorts. Some, like Psyche, are rich in metal and likely cores from bygone planetesimals. Others are like Vesta, hefty round bodies covered with craters and troughs. But then, there are space rocks like Itokawa.

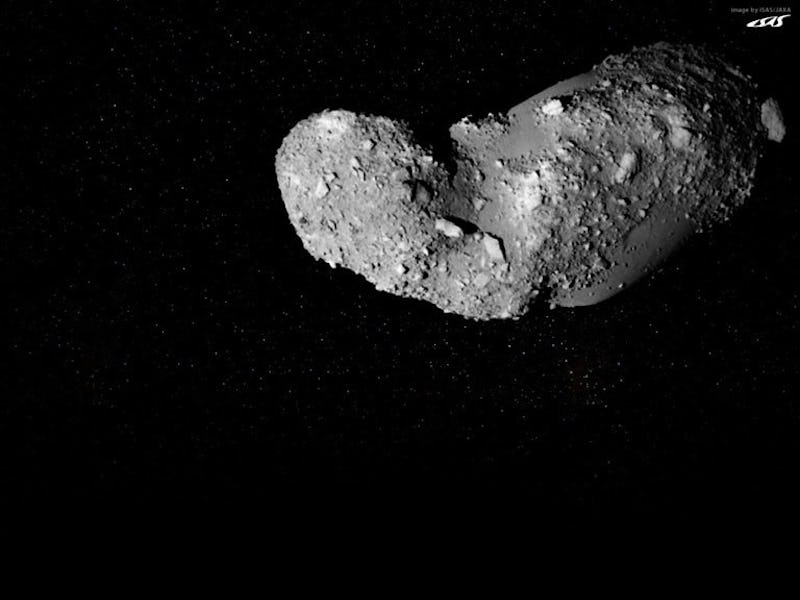

Some say it looks like a sea otter. It’s a unique class of odd-shaped asteroid, called a rubble pile, that formed when an ancient rock was destroyed by some unseen force and its individual pieces came back together. To learn more about Itokawa, Japan sent Hayabusa — which translates to “peregrine falcon” — to visit in 2005 and scoop up samples. It became the first asteroid sample retrieval mission in the world. Hayabusa’s successor delivered samples from another rock in 2020, and for that reason, geochemist Fred Jourdan thinks Itokawa is a bit forgotten.

Now that Hayabusa2’s samples from another asteroid are on Earth, Itokawa is a bit of “an old story” for some people, Jourdan tells Inverse. But Jourdan, a professor at Curtin University in Australia, finds them “fantastically useful.” A paper published Monday in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences details how Jourdan and his team uncovered new information from the tiny pieces of Itokawa.

They discovered Itokawa is older, and therefore more resilient, than once thought. Jourdan says this matters if we one day need to defend Earth from this sort of asteroid.

Asteroid Itokawa is shaped like a sea otter. Science communicator Emily Lakdawalla drew a face and hands onto the image of the asteroid from Hayabusa, to highlight its resemblance.

Here’s the background — “Itokawa is a rubble pile asteroid. That means it’s made of tons of different rocks and boulders. It’s not like a giant rock,” Jourdan says. “The analogy I want to use when I explain to people or my students is, if you go in a river near mountains, you’re going to have pebbles. And all the pebbles, they come from different mountains. But they all group together in the river. So they all have a different story to tell.”

Some rocks experienced different phenomena than others, so in an effort to gain a comprehensive look at Itokawa, Jourdan has studied samples of this oblong rubble pile more than once. In his first study on Itokawa, published in 2017, he studied two samples.

“When, in 2010, JAXA (the Japanese space agency) brought back some samples from an asteroid for the very first time, I was really excited,” Jourdan relays with enthusiasm. He said working on these tiny parcels was the opportunity of a lifetime.

What they did — The new study looked at three samples of Itokawa. One of their two main techniques was electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD), to see when the crystal in the samples was shocked by an impact (deformed look) or not (uniform). The second was argon-argon dating, to see over how much time its potassium — like that found in bananas, our bodies, and rocks — has decayed. The work revealed a surprising new timeline for when Itokawa’s parent body got destroyed.

“The first study suggests that Itokawa was formed 2 billion years ago. Which was already really old! But the new one, the data that we got shows that it formed before 4.2 billion years ago,” Jourdan says.

“So it’s super, super old. Almost as old as the Solar System, much older than what we think it would be.”

This age is the last time that the rocks got thermally reset, so to speak. The pieces of Itokawa once belonged to a solid asteroid, and what Jourdan is looking for is when that ancient rock “completely shattered” into rubble, some of which reassembled to create Itokawa.

Estimates reveal the parent asteroid was at least 20 kilometers wide. Today, Itokawa’s length is just half a kilometer.

Why it matters — Remember Vesta? It’s a celestial body large enough to have volcanism, where rocks go through metamorphosis a bit like on Earth. But those on Itokawa have not gone through those transformations, leaving them rather pristine since the Solar System’s dawn.

Not only does Itokawa help paint a portrait of what’s out there, and how our cosmic neighborhood originated and came to look as it does today, but it can reveal how to keep Earth safe.

Rubble pile asteroids like Itokawa might respond differently to a nudge from a spacecraft, a technology demonstrated just a few months ago by NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART).

A television at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida, captures the final images from the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) moments before it smashed into asteroid Dimorphos on September 26, 2022.

“You can test that in your own backyard. You hammer a solid rock, you can break it into two. You hammer a pile of sand, not much is going to happen.”

What’s next — Jourdan wants to continue studying Itokawa samples. Japan approved his request for more, and his team is in the midst of studying four new samples.

Jourdan also looks forward to the delivery of another asteroid sample return mission, NASA’s OSIRIS-REx, from the rock Bennu later this year.

This article was originally published on