30 years after its discovery, astronomers realize first confirmed exoplanet is truly rare

Worlds circling pulsars are a cosmic rarity, according to a new study.

In 1992, astronomers discovered the first exoplanets in an unexpected part of the universe: around a pulsar, a rapidly spinning stellar corpse.

Not many other pulsar planets have been found since then, and with potentially good reason: In new research detailed July 12 at the National Astronomy Meeting in England, astronomers now find that such pulsar worlds may prove incredibly rare.

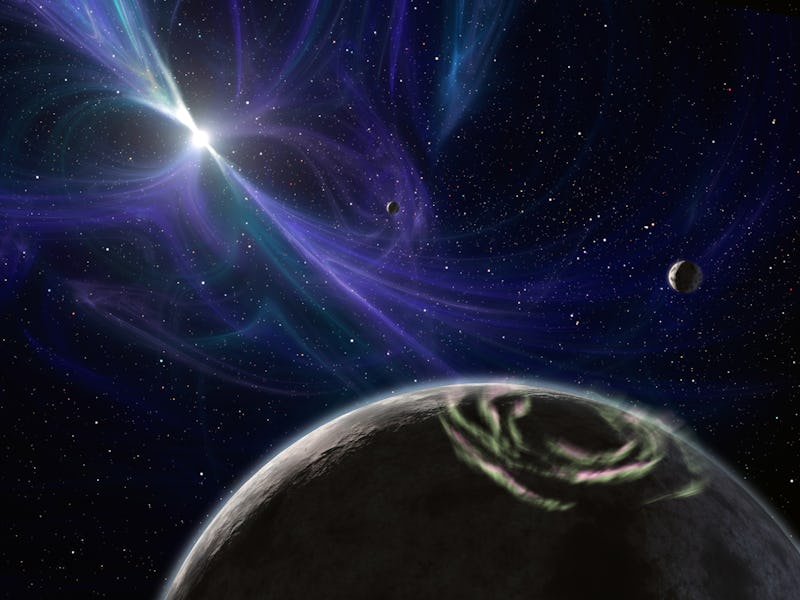

Here’s the background — Astronomers discovered the first known exoplanets around the pulsar PSR B1257+12 in 1992, located roughly 2,300 light-years away from Earth in the constellation Virgo. A pulsar is a kind of neutron star, the corpse of a star that died in a catastrophic explosion known as a supernova, whose gravity is strong enough to crush protons together with electrons to form neutrons — but not massive enough to become a black hole.

The violent nature of a supernova often send the remains of its progenitor star whirling. A rotating neutron star can spin up to 700 times per second, emitting narrow beams of radio waves from its magnetic poles that flash like lighthouse beacons, earning it the name "pulsar," which is short for "pulsating star."

If a pulsar is orbited by a planet, the pulsar will wobble slightly due to the gravitational pull from this world. "We can detect the pulses from the pulsar arriving earlier or later than expected because of this tiny motion," study senior author Michael Keith, an astrophysicist at the University of Manchester in England, tells Inverse. "This technique of pulsar timing is extremely sensitive, as we can track every rotation of the pulsar over many years."

PSR B1257+12 is now known to host at least three planets similar in mass to our Solar System's rocky planets. Although scientists have detected nearly 5,000 exoplanets in the 30 years since then, only five other pulsars are known to host anything resembling a planet. These likely did not form around these pulsars like regular worlds. The companions of four of those five pulsars are cold dead stars known as white dwarfs that have cooled off and becomes stripped of enough material to become "diamond planets." The fifth pulsar's companion, a super-Jupiter planet, was likely captured from the partner star of the pulsar.

All in all, PSR B1257+12 is currently the only known example of a neutron star with Earth-mass planets. Much remains unknown about how such worlds might form and survive around pulsars.

WHAT DID THE SCIENTISTS DO? — Astronomers performed the largest search for planets orbiting pulsars to date. Discovering how common pulsar planets may or may not be is a key first step in finding out how they might form in the first place, says study lead author Iuliana Nițu at the University of Manchester.

"Since the first pulsar planet was discovered, it has generally been thought that these are very rare," Keith says. "However, this is the first time we have made a very thorough search for any other planets."

The researchers analyzed data from roughly 800 pulsars the Jodrell Bank Observatory in Cheshire, England, has followed over the past 50 years. They looked for worlds ranging from one-hundredth the mass of the moon to 100 times the mass of Earth. The hunt involved orbits that would take planets anywhere from 20 days to 17 years to complete, ones with both circular and more "eccentric" oval shapes. A supernova may almost entirely disrupt its progenitor star's planetary system, "and any remnants of the planets might find themselves on highly eccentric orbits, barely clinging on to the pulsar," Keith says.

Planets like those around PSR 1257+12 may be very rare.

WHAT DID THEY FIND? — The scientists discovered the first known exoplanet may be extraordinarily rare — fewer than 0.5 percent of all known pulsars can host Earth-mass planets. "It is surprising that one pulsar is known to have three planets, and we see none elsewhere," Keith says.

Two-thirds of the roughly 800 pulsars also appear highly unlikely to host any companions more than two to eight times Earth's mass. One pulsar, PSR J2007+3120, may potentially host at least two exoplanets, with masses a few times that of Earth's and orbits that would take about 1.9 and 3.6 years to complete. Long-term observations using highly sensitive instruments such as the upcoming Square Kilometer Array may help confirm if it may or may not possess worlds, the researchers say.

"Earth-mass planets around pulsars would be nothing like the Earth — likely barren rocks blasted by high-energy radiation from the pulsar," Keith says.

One scenario in which a pulsar most come to host a planet suggests that matter blown off a star after a supernova could collapse to form a world.

"The material that is blown off the star is not so different to the material that originally formed the star, and so it is not impossible that a similar disk of gas and dust may form around the pulsar that is similar to that which formed our own solar system," Keith says. "This scenario seems very plausible, but it is a mystery as to why this only seems to have happened for one pulsar."

WHAT'S NEXT? — The new data on these pulsars will help scientists learn more about these dead stars, "which are exotic objects at the extremes of physics," Keith notes. The astronomers will also make their planet-hunting algorithms publicly available so that other scientists can analyze their own databases for pulsar worlds, he adds.