'Anti-gravity' experiment defies physics using one simple trick

Is physics broken?

There are certain physical phenomena we take for granted, like gravity tugging us to down to the Earth, or the refraction of light coloring the sky blue.

But in research published in September in the journal Nature, a team of physicists broke one of these seemingly 'natural' principles: buoyancy.

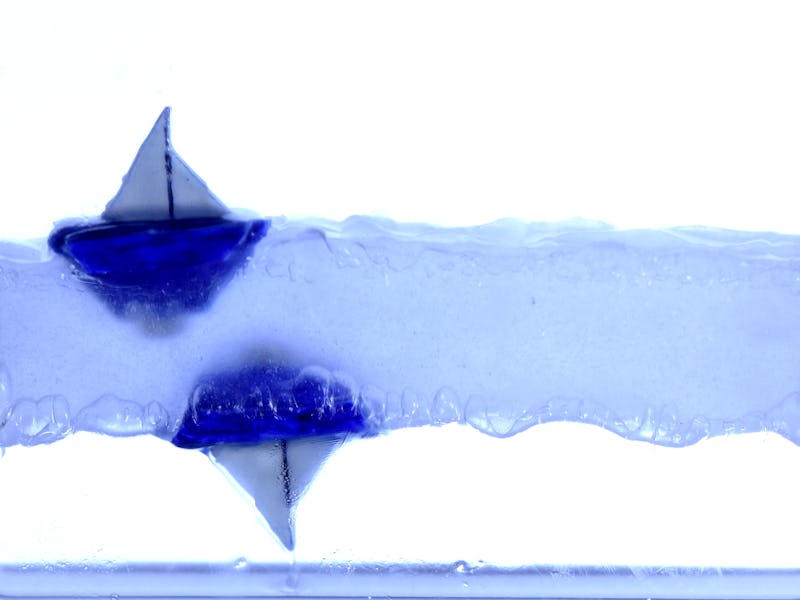

Using an experimental protocol involving dense liquids, vibrating plates, and toy sailboats, these scientists demonstrated a kind of "anti-gravity" allowing boats to sail upside down with ease. This discovery could have huge implications for other fields, including chemical engineering.

INVERSE IS COUNTING DOWN THE 20 STORIES THAT MADE US SAY 'WTF' IN 2020. THIS IS NUMBER 1. SEE THE FULL LIST HERE.

Here's the background — Under normal conditions, buoyancy works by balancing the upward force of a surface (like water) against the downward force of gravity. This delicate balance, as well as objects' varying densities and weights, is what allows ships to sail on top of the ocean instead of sinking beneath it.

This idea, which was famously discovered by Greek physicist and mathematician, Archimedes, is known as Archimedes Principle.

What's new — The Archimedes Principle holds true in everyday life, but this team of physicists wanted to find out just how far they could take it — and break it. For example, what if the buoyant surface were set to vibrate at just the right frequency?

By carefully vibrating these glass chambers, scientists were able to levitate the liquid inside.

The question may seem trivial, but Russian Nobel laureate and physicist, Pyotr Kapitza, discovered in 1951 that applying vibrations to a pendulum could cause strange physical properties to arise, such as a second point of equilibrium that allowed the pendulum to oscillate as if against gravity.

In this new experiment, the physicists decided to vibrate an enclosed glass chamber of glycerol and silicon oil to see if they could find a similar sweet spot.

What they discovered — In a normal, non-vibrating environment, scientists would expect a highly viscous fluid like glycerol to ooze down the sides of the glass chamber and settle at the bottom, displacing the air that had previously been there. But the team found that vibrating the chamber drastically changed this behavior.

Instead of leaking to the bottom, they observed that the glycerol solution instead levitated in the middle of the chamber on top of the air cushion it would've otherwise displaced.

Using a magnet to guide small boats in the chamber, the researchers were able to stably float the ships on both the top and bottom of the liquid. This upside-down ship was held in place by both the downward forces of gravity and upward forces of the air cushion beneath.

Far from breaking physics, this experiment demonstrates that there's still so much more left to discover about the quirks and nuances of our physical world.

INVERSE IS COUNTING DOWN THE 20 STORIES THAT MADE US SAY 'WTF' IN 2020. THIS IS NUMBER 1. READ THE ORIGINAL STORY HERE.

This article was originally published on