Ancient stone tools found in India tell an inspiring story about early humans

We were not meant to survive this.

A new discovery challenges a truly metal theory of early human history that weaves together a super-eruption, a “volcanic winter,” and the near extinction of human beings.

It also pushes back the timeline for the colonization of Earth by Homo sapiens, suggesting modern humans took over the planet far earlier than previously thought.

Here is what we do know:

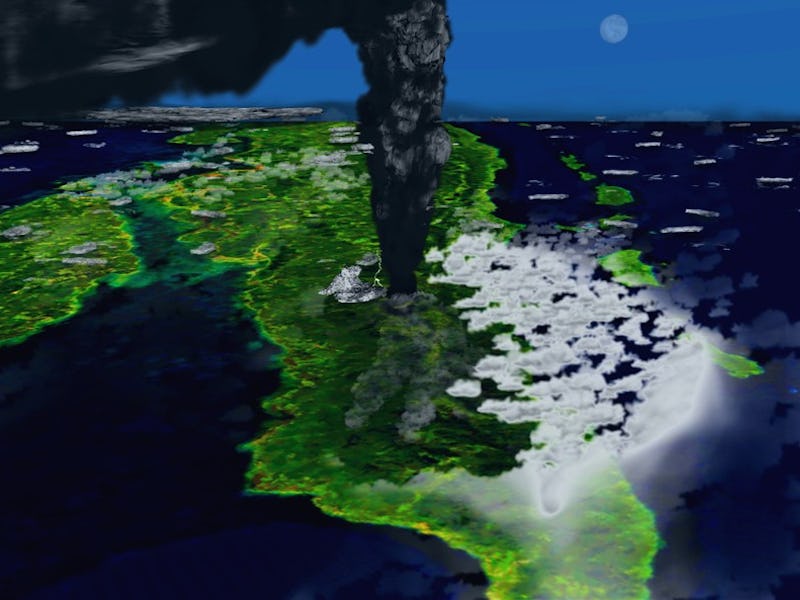

Some 74,000 years ago, a supervolcano at the site of present-day Lake Toba in Sumatra, Indonesia exploded. That event is considered the largest volcanic eruption of the last two million years — about 5,000 times larger than the eruption of Mount St. Helens in 1980.

What happened after that, however, is a matter of some debate.

According to the widely-accepted “Toba catastrophe theory,” the eruption was so world-altering that it blanketed Earth in ash, caused temperatures to plummet across the planet, and rapidly (and almost permanently) killed off people.

But that might not be the case. A study published Tuesday in Nature Communications suggests that, while the super-eruption happened and was definitely hardcore, the consequences as per the Toba catastrophe theory are exaggerated.

Senior author Michael Petraglia, professor at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, tells Inverse that this new study argues that “the effects of the Toba super-eruption were not as catastrophic as previously believed.”

Instead, the super-eruption is really a story about survival. It is also proof that in the face of sudden ecological change, humans were able to adapt — and live.

Disproving the idea of a "genetic bottleneck"

The catastrophe theory was first mooted in 1998, by University of Illinois anthropologist Stanley Ambrose. It argues that, after Toba’s incredible eruption, a resulting volcanic winter disrupted human dispersal out of Africa. The few humans who did not perish in the aftermath worked together to survive, so the theory goes, and eventually left Africa around 60,000 years ago.

Stone tools found at a site corresponding with the Toba volcanic super-eruption.

But a number of recent studies dispute this timeline and suggest Homo sapiens left Africa far earlier. This new study adds the evidence against the theory. It effectively demonstrates that “human populations were in South Asia earlier than the genetic bottleneck age of 60,000 years ago," Petraglia says.

His certainty rests on one key discovery: A collection of stone tools, found at a site in the Middle Son Valley, a region in northern India. The tools ranging in age from about 48,000 years ago to 80,000 years ago. These dates suggest that, in this part of the world, local human populations survived the Toba super-eruption

When Homo sapiens arrived in India is a focus of “intense debate,” the researchers say. So far, no human fossils from the time of the Toba super-eruption have been found in India. But this rich collection of tools suggests that humans were already living in northern India before the eruption occurred — and continued to do so afterward, too.

In turn, human dispersal out of Africa, and “most importantly east of Arabia,” must have taken place prior to 60,000 years ago. Future cultural and fossil evidence from sites dating to this period will be important for testing this hypothesis, the researchers say.

The excavation in the Dhaba site, located in the Middle Son Valley, India.

The tools that date to 80,000 years ago are of a designed known as “Levallois core assemblage.” These are stone tools created by flint knapping. Similar tools have also been found in southern Arabia, dating to between 100,000 and 47,000 years old, and in northern Australia, dating to about 65,000 years old. Together, they suggest that tool-using humans moved through the world on an earlier timeline than scientists once thought.

“Our model is one of multiple dispersals of modern humans out of Africa, using terrestrial routes,” Petraglia says.

“This is opposed to the idea that modern humans only dispersed once 60,000 years ago, utilizing the coastlines to get to Australia.”

Now, the team has to hunt for more evidence to prove their re-telling of history is true. They are in the midst of interdisciplinary archeological excavations in Sri Lanka. These could reveal if the populations living there experienced a similar fate post-Toba.

In 2018, scientists discovered that Homo sapiens living in South Africa appeared to not only survive but thrive, after the Toba event. At the time, Petraglia commented that researchers were “not seeing all the drama” predicted by the catastrophe theory — now, it is evident that they can’t find the drama elsewhere.

Abstract: India is located at a critical geographic crossroads for understanding the dispersal of Homo sapiens out of Africa and into Asia and Oceania. Here we report evidence for long-term human occupation, spanning the last ~80 thousand years, at the site of Dhaba in the Middle Son River Valley of Central India. An unchanging stone tool industry is found at Dhaba spanning the Toba eruption of ~74 ka (i.e., the Youngest Toba Tuff, YTT) bracketed between ages of 79.6 ± 3.2 and 65.2 ± 3.1 ka, with the introduction of microlithic technology ~48 ka. The lithic industry from Dhaba strongly resembles stone tool assemblages from the African Middle Stone Age (MSA) and Arabia, and the earliest artifacts from Australia, suggesting that it is likely the product of Homo sapiens as they dispersed eastward out of Africa.