An Ancient Magma Ocean Once Covered the Moon, India’s Pragyan Lunar Rover Reveals

The Moon was probably once a gooey ball.

A year ago, India’s Pragyan rover began a nine Earth-day-long trek across a mysterious region of the Moon.

The robotic explorer encountered both smooth terrain as well as places filled with boulders likely flung out from craters. Despite this variety, the lunar dirt it observed at 23 different stops along its path was actually uniform in composition. When Pragyan probed the ingredients of this surface material, called regolith, it wound up boosting the idea that the Moon once harbored a subterranean magma ocean.

The findings appear in a new study published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

The idea is that when an ancient object careened into Earth, material sloshed off into space. Eventually it came together into a gooey ball, and cooled down in an uneven manner. The Moon was somewhat like a chocolate-covered cherry. The magma slush was filled with different elements. As the proto-Moon cooled down, light material started to crystallize. It floated to the surface. Once in place, it formed a lid. Now, with the frigid environment of space cut off from the hotter material underneath the surface, the Moon’s magma ocean couldn’t cool down as fast.

The rover found that the terrain in the 23 places it stopped, all within 50 meters of the mission’s Shiv Shakti Point landing site, was uniform and mostly made up of ferroan anorthosite.

It’s a fresh check-mark for the LMO hypothesis: If the lunar magma ocean existed in the distant past, the anorthosite would have formed as the crystals during the early cooling process rose to the surface, and made the Moon’s crust. And billions of years later, India’s Pragyan rover would roll its tires over a stretch of this land and study it up close.

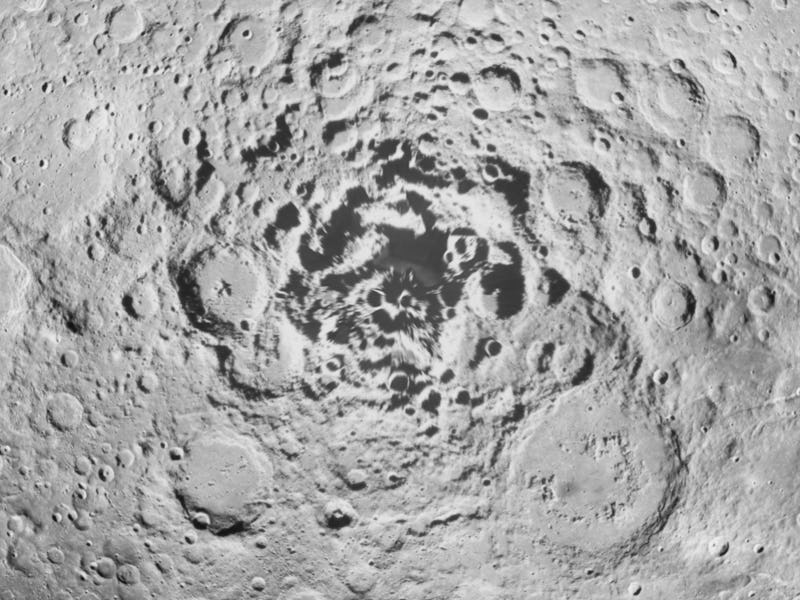

Pragyan rover is part of the country’s Chandrayaan-3 mission. Its Shiv Shakti Point landing site is located about 350 kilometers from one of the Moon’s most exciting places: the South Pole Aitken (SPA) basin.

It’s the largest impact basin in the Solar System, and the oldest on the Moon. It’s packed with clues about the Moon’s history.

NASA also wants to place astronauts there someday. According to a space agency white paper, the south pole of the Moon has good lighting conditions, including places where sunlight is continuous throughout the year. Plus, ice may be trapped here. This could be a valuable resource for astronauts, and could sustain their missions by offering a local source of water and potentially fuel.

Pragyan was exploring a prime place, for more reasons than one.

In a little more than a week, Pragyan had gained a precise analysis backed up by data from instruments delivered to the Moon via India’s two lunar missions, Chandrayaan-1 and Chandrayaan-2.

Pragyan reinforces findings from American and former Soviet Union missions half a century ago. While Pragyan regolith data wasn’t a perfect match with the findings from the 1972 missions — NASA’s Apollo 16 and the Soviet Union’s Luna 20 — it was very close. Since the three missions had landing sites that were geographically well separated, the study authors said, the similarities in regolith data across them all reinforces the hypothesis that the Moon did have a magma ocean. And that the natural satellite’s first stage of development did involve a differentiation, or split, between the light stuff that floated to the top, the heavier elements that sunk below, and the hardening of the crust that made the subterranean lunar magma ocean cool down slower.

The lunar south pole is undeniably a portal to probing the Moon’s past and the lofty ambitions of space exploration’s future.