Amphibians may share a bizarre trait that lets them see in the dark — study

Shine on.

The ability to glow in the dark, known as biofluorescence, may be far more common throughout the animal kingdom than we ever realized.

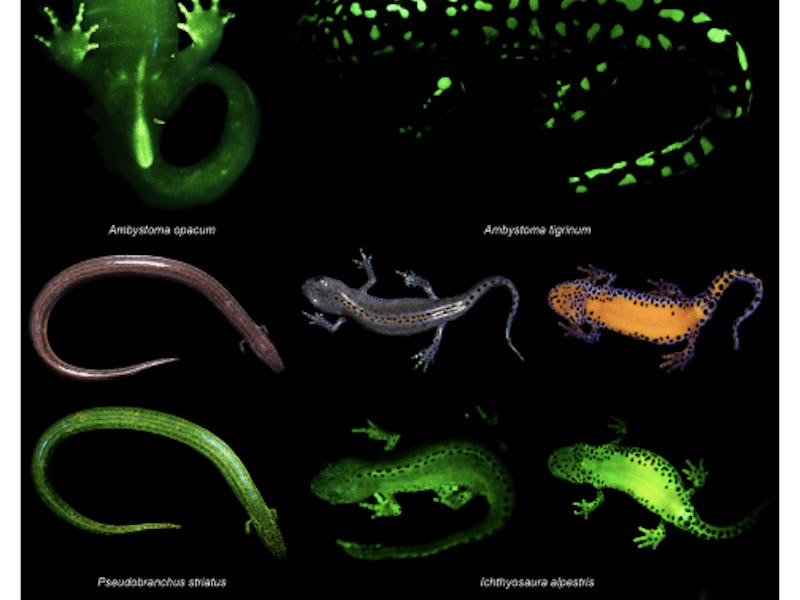

In a new study, biologists reveal that dozens of species of amphibians are able to glow in the dark, although some shine brighter than others.

Unlike bioluminescent animals that emit light (think anglerfish), biofluorescent creatures absorb energy and then emit it as a glow. For this study, researchers exposed individuals from 32 amphibian species, including salamanders, frogs, and toads, to blue or ultraviolet light. They then used a spectrometer to measure the wavelengths of light the animals released.

Shockingly, all of the species examined turned out to be biofluorescent. Some species showed just blotches or stripes, others had glowing bones, and some were fully aglow.

Previously, scientists thought biofluorescence was a rarity among amphibians, a group of animals that includes frogs, toads, and salamanders. But the new findings confirm that the trait is not limited to one family of salamanders — in fact, the ability to glow in the dark may be the rule, rather than the exception.

The eastern tiger salamander (left) and anuran (right) show different patterns of biofluorescence.

“We show for the first time that fluorescence is widespread across Amphibia,” the study authors, researchers Jennifer Lamb and Matthew Davis from St. Cloud State University in Minnesota, say in the paper.

The new study appeared Thursday in the journal Scientific Reports.

Glowing in the dark: A secret weapon

Glowing in the dark may confer another nifty skill on these creatures, the scientists say: The ability to see in the dark. Their eyes pick up green and blue light particularly well, which means they may be adept at spotting fellow glowing creatures in low light.

Biofluorescence may also play a role in camouflage, choosing a mate, or even the ability to mimic predators. These traits have been shown in other animals that glow, the researchers say, although it is too soon to conclude whether frogs and salamanders do the same.

Glowing secretions from a caecilian (left) and giant salamander with glowing urine (right).

The new study also suggests that glowing in the dark is not a new skill for amphibians — even if we humans had no idea most of them were doing it until now. Because the phenomenon is so widespread among different amphibian species, that suggests the common ancestors of modern amphibians must have been able to glow in the dark, too.

What makes animals glow?

These slimy critters are far from the only animals that can do this. Aside from amphibians, scientists have found biofluorescent sea turtles, corals, fish, sharks, penguins, parrots, scorpions, and insects, among other creatures.

Biofluorescence involves absorbing energy and re-emitting it as light — but how that actually works involves some very cool science. Fluorescent proteins and compounds in the skin, bones, or secretions of these animals may underlie the ability to glow. In salamanders, for example, the animals secrete biofluorescent urine and mucus-like goo.

Biofluorescence may also relate to the chemical and structural composition of some amphibians' chromatophores (pigment-containing and light-reflecting cells), the authors say. Now that scientists know more of these creatures glow, they can begin to answer these questions with further studies.

The results “provide a roadmap for future studies” to characterize the mechanisms and evolutionary reasons behind biofluorescence in amphibians, the researchers say. At least it will be a well-lit road.

Abstract: Biofluorescence is the absorption of electromagnetic radiation (light) at one wavelength followed by its reemission at a lower energy and longer wavelength by a living organism. Previous studies have documented the widespread presence of biofluorescence in some animals, including cnidarians, arthropods, and cartilaginous and ray-finned fishes. Many studies on biofluorescence have focused on marine animals (cnidarians, cartilaginous and ray-finned fishes) but we know comparatively little about the presence of biofluorescence in tetrapods. We show for the first time that fluorescence is widespread across Amphibia, with a focus on salamanders (Caudata), which are a diverse group with a primarily Holarctic distribution. We find that biofluorescence is not restricted to any particular family of salamanders, there is striking variation in their fluorescent patterning, and the primary wavelengths emitted in response to blue excitation light are within the spectrum of green light. Widespread biofluorescence across the amphibian radiation is a previously undocumented phenomenon that could have significant ramifications for the ecology and evolution of these diverse and declining vertebrates. Our results provide a roadmap for future studies on the characterization of molecular mechanisms of biofluorescence in amphibians, as well as directions for investigations into the potential impact of biofluorescence on the visual ecology and behavior of biofluorescent amphibians.