Deformed disc of gas and dust in the Orion constellation could birth even weirder planets

"It’s a new mechanism of forming planets."

In the infinite cosmos, planets are birthed from the swirling disc of gas and dust that form around young stars.

In our own Solar System, this disc was relatively stable and flat, resulting in Earth and other planets of the Solar System all orbiting on the same plane.

But not all planets may be so lucky. Recent observations of a strangely warped disc in the Orion constellation reveal it was likely torn apart by its own stars — a catastrophic process. The disfigured disc may in turn give rise to even stranger planets, a new study suggests.

The new finding is detailed in a study published Thursday in the journal Science.

Using the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (ESO’s VLT) and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA,) a team of astronomers found the first direct evidence that stars can tear apart the planet-forming, or circumstellar, disc that surrounds them. The result is a broken-apart disc with a misaligned inner ring, where a giant planet may soon form.

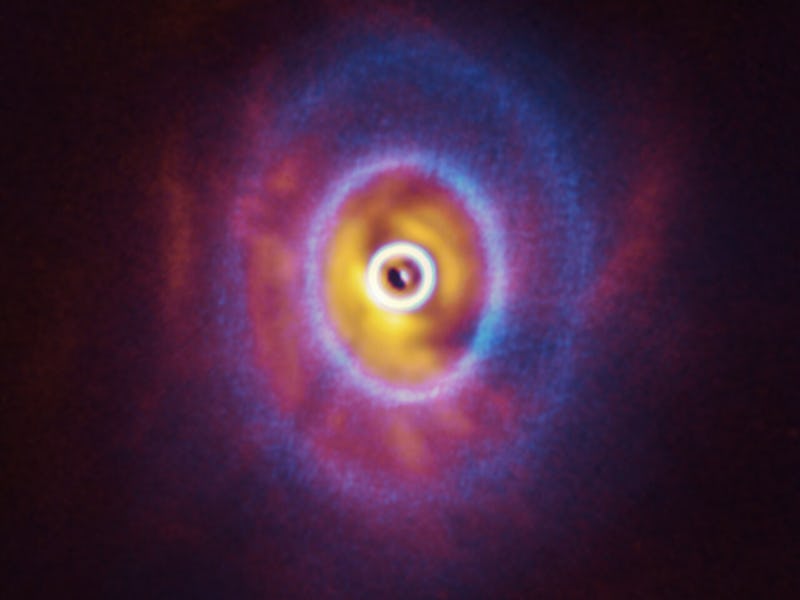

The image on the right is the image taken of the disc, with the misaligned ring while the left image is an artist's impression of what the inner ring would look like while surrounded by the disc.

Stefan Kraus, an astrophysics professor at the University of Exeter and lead author of the new study, has been observing the star system for more than a decade.

"It’s one of the very few star systems where we know all the orbits of the stars of the system, and we know all their properties," Kraus tells Inverse. "Since we know the specific orbits that the stars are on, we can simulate what happened."

The GW Orionis star system is made up of three stars, and is located 1300 lightyears away from Earth in the constellation of Orion.

The three stars do not orbit in the same plane. Rather, their orbits are misaligned with one another and with the circumstellar disc that surrounds them.

Based on what they already knew about the star system, the team behind the new study combined observations with computer simulations to reconstruct what happened over the lifetime of GW Orionis. The simulation revealed that the stars had torn apart their disc themselves due to their conflicting gravitational pull, with each one pulling on the disc in a different direction.

"We started with the disc, then we put in the orbits of the stars that we measured over 11 years to see how the system evolved," Kraus says. "And it shows that the tearing effect is kicking in and is tearing the disc apart."

The circumstellar disc was broken apart into smaller rings in the simulation, which matches the astronomers' observations of the star system.

Astronomers had long theorized this disc-tearing effect may occur, but this marks the first time the effect has been observed in a real star system.

This composite image shows both the ALMA and SPHERE observations of the disc, with the rings separated from the disc.

Are there exoplanets in Orion? — Interestingly, the inner ring of the disc contains at least 30 Earth-masses of dust, which could be enough to form planets.

"The intriguing thing is that the planets that would form there would be on completely tilted and highly eccentric orbits," Kraus says. "It’s a new mechanism of forming planets."

The researchers have already scheduled future observations of the star system to image it in more detail, and find out if planets could form within the inner region of the disc so close to the stars.

Abstract: Young stars are surrounded by a circumstellar disk of gas and dust, within which planet formation can occur. Gravitational forces in multiple star systems can disrupt the disk. Theoretical models predict that if the disk is misaligned with the orbital plane of the stars, the disk should warp and break into precessing rings, a phenomenon known as disk tearing. We present observations of the triple star system GW Orionis, finding evidence for disk tearing. Our images show an eccentric ring that is misaligned with the orbital planes and the outer disk. The ring casts shadows on a strongly warped intermediate region of the disk. If planets can form within the warped disk, disk tearing could provide a mechanism for forming wide-separation planets on oblique orbits.