Space scientists use 3.2 billion-pixel camera to take largest photo ever

At 250 times the resolution of most smartphone cameras, it will reveal facets of the cosmos as we have never seen them before.

If you've ever lamented over how your pores look in a high-res photo, then you might want to avoid having your picture taken by the Stanford SLAC laboratory's ultra-sensitive, 3.2 billion-pixel camera.

Space scientists plan to use this SUV-sized camera to take huge, sweeping pictures of the southern sky as part of something called the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST).

The survey will help scientists literally see our universe better than ever before and help them resolve some of astronomy's big mysteries, like how galaxies evolve, and how theories about dark matter and energy collide with reality.

But before the camera makes its final journey from Northern California to Chile's Rubin Observatory, the Stanford team snapped a few practice shots.

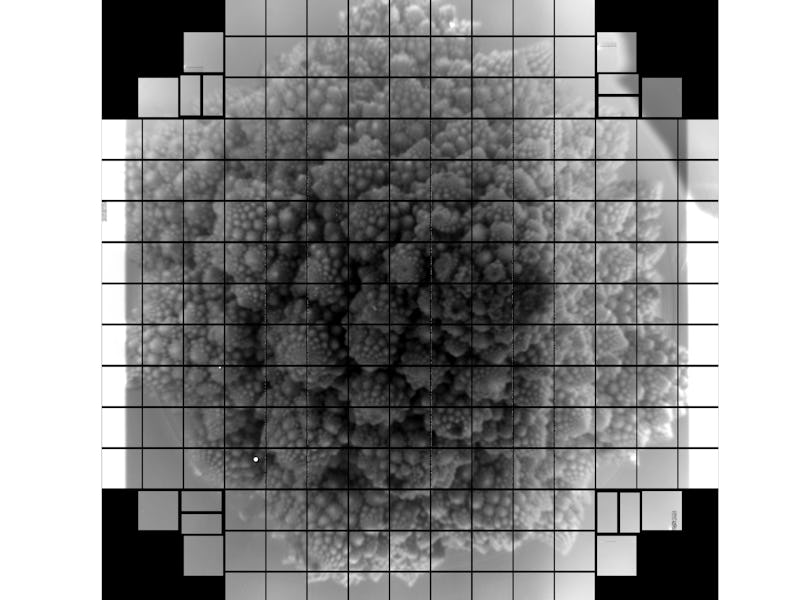

These 3,200-megapixel photos of intricate (albeit it, strictly terrestrial) objects like a head of romanesco are the largest single photos ever taken.

A picture of a vegetable may not sound like the most exciting development, but Vincent Riot, the survey's camera project manager at the Department of Defense's Livermore National Laboratory, said in a statement that these first photos represent an incredibly important step toward demonstrating how the camera will fair when photographing space.

“This is a huge milestone for us,” said Riot. “The focal plane will produce the images for the LSST, so it’s the capable and sensitive eye of the Rubin Observatory.”

A 3200-megapixel snapshot of a common romanesco.

How they did it — The basic design of the camera is no different from the camera in your average smartphone — light emitted from an object or reflected by an object is captured by light-sensitive components and converted into electric signals. These signals can be translated into exact pixel information to piece together a photo.

What stands out about this camera's design is that has 189 individual light sensors, all bringing in 16-megapixels of information. For comparison, a standard cellphone only brings in up to 16 megapixels in total, 1/189 the power of this camera.

At any one time, nine of the sensors are grouped together to form what the team calls a "science raft." Each sensor is two-feet tall and weigh in at 20 pounds. Not to mention, they are $3 million apiece.

"We pretty much nailed it.”

The camera itself is composed of 21 of these science rafts, plus four additional, non-imaging rafts to help hold them in place. Together, these sensors are used to create a focal plane — the area in front of the camera in which objects are in focus — capable of spotting and resolving images a hundred times dimmer than what the naked eye can see, for example, a candle that is hundreds of miles away.

But clicking these science rafts into place to create this high-resolution image is not an easy task. The rafts have to be carefully positioned less than a hair's width apart from each other — a delicate task, as accidentally bonking them together can cause detrimental cracking. It was an incredibly sensitive job, a SLAC mechanical engineer who worked on the project, Hannah Pollek, said in a statement, but the team rose to the occasion.

“The combination of high stakes and tight tolerances made this project very challenging. But with a versatile team we pretty much nailed it," she said.

A historic astronomical engraving also captured by the camera.

See also: A new 10 trillion frame per second super camera can freeze time

What were the results — The camera's construction was interrupted due to Covid-19 in March 2020, but the team began safely returning to the lab in May to test the camera. While not quite decked out with its full lens kit, the team was able to trick the camera into taking high-resolution photos in the lab by projecting light through a 150-micron pinhole. The team tested the camera out on objects like romanesco, a vegetable known for its fractal-like qualities, a 19th-century French engraving of the sky, and a photo of Vera Rubin, the influential astronomer for whom the Chile observatory was named.

These 3200-megapixel images are the largest, single-shot photos ever taken and require nearly 400 4K, ultra-high-def TV screens to be displayed in full. For comparison, a phone might capture 12 megapixels in a single image.

What's next — Up next for this super-sensitive camera will be to add its final components, like its lenses, shutter, and filter exchange system, so it's ready to photograph the night sky. The camera is slated to make its move to Chile in 2021 for final testing and integration into the Rubin Observatory, the team says.

JoAnne Hewett, SLAC’s chief research officer and associate lab director for fundamental physics, said in a statement that this milestone will bring humanity closer than ever to understanding our place in the universe.

“Nearing completion of the camera is very exciting, and we’re proud of playing such a central role in building this key component of Rubin Observatory,” said Hewett in a statement.

“It’s a milestone that brings us a big step closer to exploring fundamental questions about the universe in ways we haven’t been able to before.”

Inverse always includes abstracts from the studies we cover, but in this case there was no associated abstract or published paper with this work.

This article was originally published on