Don't you dare tell Shaughnessy Naughton "I'm not a scientist" to make change

Let's say "I am."

In 2014, two years before Shaughnessy Naughton founded the grassroots organization 314 Action, the halls of Congress echoed with the same excuse: “I’m not a scientist.” Criticized by President Barack Obama, skewered by the New York Times, and satirized by Steven Colbert, the verbal shrug absolved many of America’s politicians from weighing in on crucial scientific topics, like the climate crisis.

So as the Earth’s land surface temperature reached a new record on a 134-year-old graph, Naughton began working on getting more scientists in office, starting with herself.

“Rather than hearing from politicians the cop-out of ‘I’m not a scientist,’” the former chemist tells Inverse, “let’s say ‘I am.’”

Naughton’s 2014 run for Congress to represent the 8th District of Pennsylvania, her home state, did not secure her a seat in the House. But it did spark an idea about how other scientists might. Painstakingly cold-calling scientists for their political support revealed to Naughton that they wanted a voice in politics, but they didn’t know how they could participate. And so she created a way to help them speak up.

"Rather than hearing the cop-out of ‘I’m not a scientist,’ let’s say ‘I am.’"

“What I realized was that there is a growing awareness — and this was pre-Trump — in the scientific community that the traditional approach of a scientist looking at politics and saying, ‘Ew, I don’t want to be a part of that’ wasn’t working,” she says. “Because politicians are unashamed to meddle in science.”

In 2016, she formed 314 Action, an organization devoted to getting STEM professionals into office, to train scientists to meddle in return. Her efforts have been exhilaratingly disruptive. The community, now nearly one million people strong, helped bring about the election of nine Democratic scientists to Congress in 2018 and over 100 STEM professionals to key legislative districts. Among them are South Carolina congressman Joe Cunningham, an ocean engineer; Illinois representative and biochemical engineer Sean Casten; and Nevada Senator Jacky Rosen, a computer scientist.

“The last class had six or seven talk radio show hosts and hundreds of attorneys,” she says of the 2015 Congress, which served under both Presidents Barack Obama and Donald Trump and also included two almond orchard owners and one screenwriter-slash-comedian. “What wouldn’t benefit by having more scientists actually at the table?”

Also read: Why we need more scientists in Congress, by Shaughnessy Naughton

Naughton has the winning smile and matching voice of a person who might breeze through politics, but she makes no airs about the difficulties of running for office when she trains scientists for the job. She experienced them first-hand, not only as a chemist but as a young woman who was completely unprepared for the demands of political life.

Her education in the chemistry labs of Bryn Mawr, investigating treatments for breast cancer and antibiotics against infectious disease, didn’t prepare her. The decade she spent working for her family’s small publishing business, which struggled during the recession, didn’t either.

By the time Congress had voted repeatedly to refute the Affordable Care Act, failed to act on gun violence after Sandy Hook, and denied America a policy protecting it against climate change, Naughton was fired up. She had a wellspring of good ideas but no way to bring them to the House. A harsh realization during her campaign run was that running for office takes money, and getting it is hard.

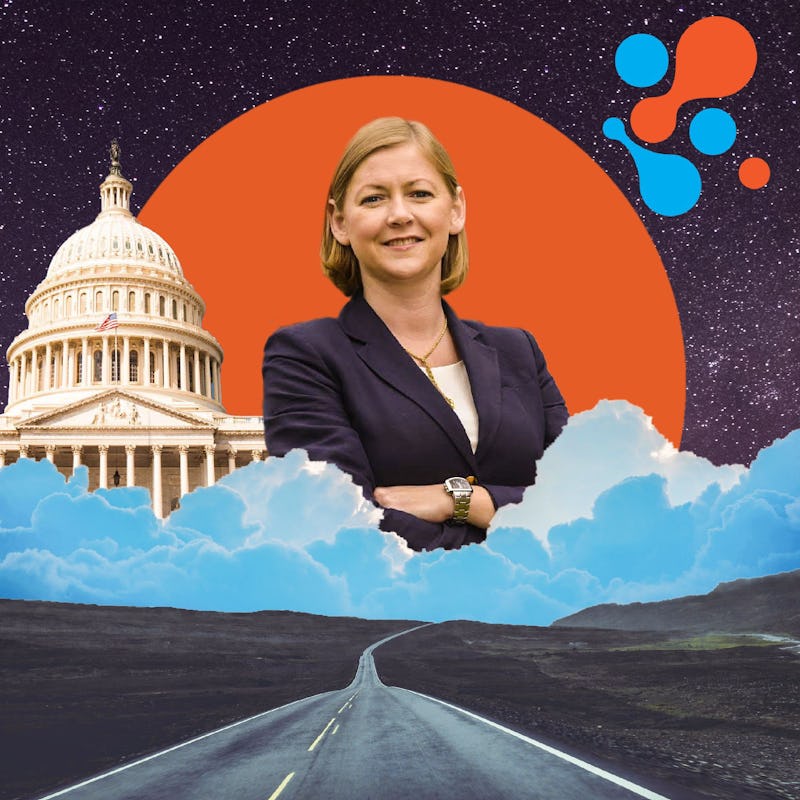

Naughton is the founder of 314 Action.

“Honestly, I had a very naive understanding of what was involved in running for Congress,” she says. “I thought it was about my great ideas.”

The first thing she was asked when she met with people in democratic politics, she recalls, was: “Well, how much money can you raise?”

To Naughton, this is an unfortunate but not insurmountable obstacle for scientists running for office. She sees the need for more STEM thinkers in American politics as too great for it to be insurmountable.

So in 314 Action’s training sessions, scientists learn how to get past those initial hurdles — mobilizing their own personal networks and building a fundraising team — giving them time to focus on honing their pro-science agendas and connecting with the public.

The lessons are, in part, inspired by Naughton’s own experience. “I’d never raised money before and turns out I was 35 at the time,” she laughs. “That’s a really bad age to be asking your friends who are just starting to write checks.”

"It’s not getting people to see your point of view. It’s about showing them how smart you are.

Across America, vehement climate denialism, obstinate gun rights advocacy, and stubborn anti-vaccination campaigns are defining a country increasingly divided along scientific lines. In this fraught environment, some will view 314 Action’s dogged support of a pro-science agenda as a beacon of hope; others will see it as an act of aggression.

Today, conversations about science are often antagonistic, but they don’t have to be, and Naughton understands that changing the dynamic can begin with a scientist. A big part of 314 Action’s training is to help candidates talk about science differently so that the deadlocked conversation might finally take a productive turn.

“It’s not getting people to see your point of view. It’s not about showing them how smart you are,” Naughton says. “It’s about connecting on really more of an emotional level than even facts and figures, which can be really unnatural for some scientists to do.”

Shaughnessy Naughton with scientist Bill Nye.

So much of the conflict over pro-science politics seems to stem from the fundamental misunderstanding that it’s designed to only benefit its supporters. Science-based legislation for cleaner air, healthier food, and less gun violence should appeal to everyone, yet it doesn’t. Perhaps it’s not so much about the data as it is about the people presenting it.

“Science is, for the most part, very rational, or at least the approach to science is. But politics isn’t necessarily,” says Naughton. “And so I think an important part is establishing those relationships so there is trust.”

Joe Cunningham, the South Carolina congressman backed by 314 Action, built a successful campaign on a promise to ban offshore drilling in the state, which appealed not only to environment-minded citizens hoping to protect the seas but also to local business owners concerned about its effect on tourism. This science-based but human-focused narrative was embraced by both Democrats and Republicans. The editorial board of The Post and Courier hailed his bipartisan appeal as “refreshing.”

Healing the divide over climate change or healthcare won’t be as easy, but Naughton stands by her belief that scientists are especially well equipped to find creative ways to solve America’s problems alongside people who don’t believe them.

“They are by nature problem solvers — by definition, almost,” she says. “They are used to working collaboratively.”

In the year ahead, Naughton and 314 Action are focused on flipping the Senate and defeating 25 climate deniers in Congress. True to their grassroots nature, they’re doing so by tackling state-specific concerns.

“We think it is very important, certainly not to lose sight of what’s happening at the federal level, but to realize the opportunities for change as at the state level,” she says.

They’ve poured their energies into Virginia, where 11 of their 13 scientists won their primaries in June. In Kentucky, they’re supporting Sheri Donahue, a cybersecurity expert who’s highlighting election security in her campaign for auditor. They are “bullish” on Arizona, where Naughton says “things are changing.” For one, Arizona Representative Raúl Grijalva, Democratic chairman of the Natural Resources Committee, has strongly opposed President Trump’s rollbacks of the Endangered Species Act.

"One of the conclusions I drew from the election of Donald Trump was that there were some people who were just voting for change."

No one knows how Congress will settle once Naughton has finished shaking it up. All she can hope for is that it will be different — at least enough that the nation can finally move past its tired stalemate over science. Her approach may be what finally does the trick: Teach candidate scientists to communicate with Americans who are scared, wary, and mistrustful of science so they can show them that the changes it can bring are for them, too.

“One of the conclusions I drew from the election of Donald Trump was that there was a certain segment of people who voted for him because they liked what he was saying, and there were some people who were just voting for change,” Naughton says.

“And what I argued, and I think it did play out, is that scientists represent change in a much more productive way.”

Shaughnessy Naughton is a member of the Inverse Future 50.

Shaughnessy Naughton is a member of the Inverse Future 50, a group of 50 people who will be forces of good in the 2020s.

Also read: Why we need more scientists in Congress, by Shaughnessy Naughton