“The significance of the story, in my opinion, is that it actually changed the direction of NASA.”

How a controversial Mars meteorite changed the search for aliens forever

President Clinton made the announcement. NASA scientists had found potential signs of life on Mars. The findings didn't hold up, but their legacy lives on.

by Jon KelveyTwenty-five years ago, at least for a moment, even the President of the United States thought it might have been aliens. At least, fossilized signs of aliens.

On August 7, 1996, President Bill Clinton addressed the nation concerning the findings of a group of NASA and Stanford scientists. Just the month before, a president spoke of aliens in the newly released Independence Day. Extraterrestrials were on the country’s mind.

The scientists found what they believed to be signs of microbial life in a meteorite found determined to be of Martian origin.

The Allan Hills meteorite, also known as ALH 84001, would go on to become one of the most studied rocks in history, leading the majority of planetary researchers and astrobiologists to ultimately decide it did not contain evidence of life on Mars.

But the real legacy of ALH 84001 lies in the debate that it caused, and the changes that debate engendered. It reinvigorated the field of astrobiology, rekindled NASA’s interest in Mars, and changed how some scientists think about life itself.

And depending on who you ask, it’s a debate that isn’t even over yet.

The debate over the Allan Hills meteorite

“The question is still open, in my opinion,” Stanford University professor Richard Zare tells Inverse. Zare was one of the original investigators of ALH 84001 and a co-author of a related paper published in the journal Science on August 16, 1996.

“It is quite possible that what we found does not indicate a relic of ancient fossil life,” he says. “It’s also possible that it will still prove they are there.”

Photograph of the Martian meteorite, ALH84001.

Zare’s lab was using lasers and mass spectrometry to study meteorites in the 1990s when he was approached by a group of scientists from NASA’s Johnson Space Center who had “a very interesting rock” they hoped he would analyze.

“They said this was a very important thing they were working on and they couldn’t tell me much about it,” Zare says. The secrecy, he would later learn, was because “they were not permitted at the time to do this kind of study by NASA at Johnson Space Center.”

It was after Zare reported his findings to the group — that the meteorite contained polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, organic molecules considered some of the starter materials for life — that they let him in on ALH 84001’s Martian origin.

Discovering the origin of the ALH 84001

Already more than 4 billion-years-old, ALH 84001 was likely ejected from Mars during a meteor impact around 3.6 billion years ago. ALH 84001 then fell through space for epochs until finally crashing to Earth in Antarctica some 13,000-years-ago.

“Knowing things for sure in science is a dangerous thing.”

A group of prolific meteorite hunters discovered the rock in 1984 and in 1996 Zare and the NASA scientists published their findings in Science. There were the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons discovered by Zare, but there were also carbonate globules similar to those left by Earthly bacteria. There wasn’t Martian life exactly, but the scientists argued they had found strong evidence of “biogenic activity” on Mars.

“There were people in this group who knew for sure what they had,” Zare says. “I never knew for sure, but I suspected they might be right. Knowing things for sure in science is a dangerous thing.”

Electron microscopy of the meteorite fragment, ALH 84001.

The debate over the findings began unusually, with the details leaked to the press by a Washington D.C. prostitute who had in turn been whispered the information by President Clinton’s adviser Dick Morris. This culminated with Clinton giving a speech before the paper was published in Science.

“It was a crazy story,” Zare says. “There was a lot of publicity around this and it certainly caused me grief.”

Some of his faculty friends, Zare remembers, would say, “I remember when Dick Zare did science.”

The scientific consensus on ALH 84001

But Zare did do good science, according to Andrew Steele, an astrobiologist who worked on ALH 84001 on the Johnson Space Center team when he was a postdoc.

“Outside of the astronomy field with the detection of exoplanets, this is probably one of the most important papers published,” with regards to astrobiology, Steele tells Inverse. Zare and the other authors of the paper should be lauded, he says, “whether they are right or wrong.”

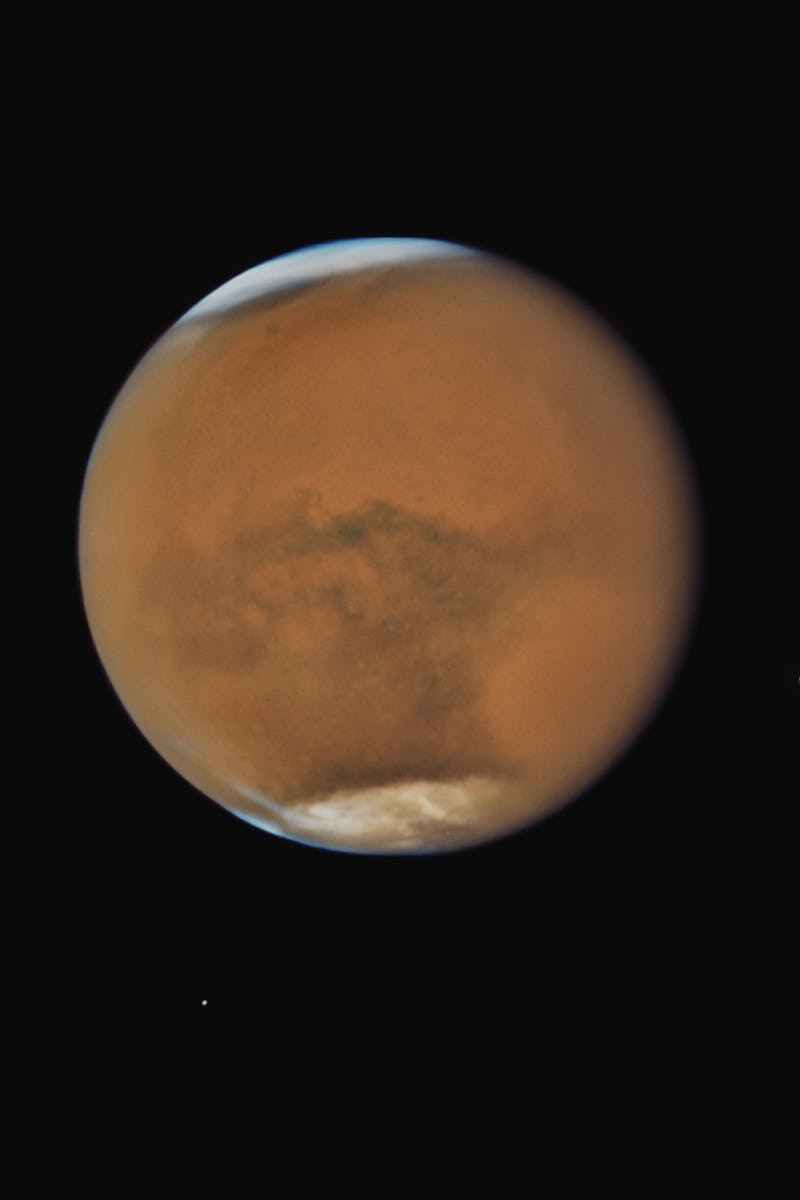

An image of the rocky surface of Mars.

Steele, now a staff scientist with the Carnegie Institute, has also studied ALH 84001 as well as meteorites like it. He does lean toward the claims of fossil life in ALH 84001 being wrong, though he won’t say it definitively.

“My work has shown there is a non-biological explanation. My observations show mechanisms of organic synthesis, abiotic mechanisms of synthesis, in ALH 84001,” he says. Regardless, this still “doesn’t mean to say that they were wrong.”

Even if they were, that makes ALH 84001 even more interesting, Steele says.

“Allan Hills is one of the oldest rocks we have from any planetary surface.”

Science is still being done on ALH 84001. Researchers in Japan recently discovered nitrogen-bearing organic material in the meteorite, adding further evidence that Mars was once a wet, potentially habitable planet.

If ALH 84001 does not provide evidence of past life on Mars, it might still tell us quite a bit about life on Earth.

“Allan Hills is one of the oldest rocks we have from any planetary surface,” Steele says, “and so if those globules are not life, or were not made by life or do not track life, then what are they?”

Even if Mars never hosted life, it may well have hosted the conditions where life could have arisen — conditions similar to those of the early Earth, evidence of which we’ll never know because of our planet’s geologic activity.

“The hard drive has been overwritten” by plate tectonics Steele says. “Allan Hills represents one of the earliest times in our solar system on a potentially habitable world, where the actions that possibly led to life are preserved.”

The legacies of ALH 84001

It’s the questions about the origins of life, how to define life, and whether scientists should look for it beyond Earth at all which are the greatest legacies spurred by ALH 84001.

“The significance of the story, in my opinion, is that it actually changed the direction of NASA,” Zare says. “Prior to that, NASA was very excited and busy about spacewalks.”

The biology experiments on Viking 1 in 1976 failed to show evidence for life, and so human space flight was where it was at. ALH 84001, Zare says, got NASA thinking about Mars again, and about the question of whether or not Earth life was alone in the universe.

Today, the NASA rover Perseverance is tasked with finding evidence of ancient life on Mars.

“This changed, really, the mission of NASA,” Zare says. “It was a good legacy.``

It also changed how scientists thought about the problem of knowing how to determine if they had discovered extraterrestrial life, whenever that might occur.

ALH 84001 contained terrestrial life that had contaminated the meteorite since it first landed, but this was often missed by scientists examining the space rock, according to Steele: “We’re having trouble finding Earth life in a Martian rock on Earth — how are we going to find life on Mars?”

The debate over ALH 84001 galvanized the scientific community and led to a total reconsideration of how to go about the study of life, wherever it might be found.

Part of ALH 84001’s legacy is on Mars right now, in the form of NASA’s Perseverance rover, which Steele notes is exploring Martian terrain of similar age and features to ALH 84001. The rover is drilling soil samples on the Red Planet, and NASA plans to retrieve them. Analysis of these samples will show how right, or wrong, we’ve been about the meteorite.

“The ultimate test of the AH 84001 hypothesis is bringing samples back from Mars,” Steele says.

This article was originally published on