Don't Freak Out About Jet Streams Crossing the Equator

There are lots of good reasons to be worried about climate change. This isn't one of them.

About a week ago, Facebook feeds lit up with the news: The jet stream is now “wrecked,” running pole to pole and confusing summer with winter. The source was a blog post by Robert Fanney, and within the first paragraph, my debunk spidey senses were positively tingling. I stopped reading when I got to the part where he tries to make sensationalistic hay of last month’s whistling Caribbean wormhole news, which according to the researchers involved is a matter of scientific curiosity, not a signal of impending doom, not even a new development.

But the idea of a radically new jet stream fueled by out of control climate change was catchy, and soon it was picked up by Paul Beckwith, a part-time professor at the University of Ottawa who is working towards a Ph.D. on “abrupt climate systems change.” Beckwith published a blog post and a YouTube video holding up Fanney’s interpretation. Considering his credentials, and the traction the posts continued to have online, I felt the whole position merited a second look.

Beckwith’s analysis makes an intuitive sort of sense. I’m familiar with the work of Jennifer Francis, an atmospheric scientist at Rutgers who has made the scientific case that a decline in the temperature differential between Arctic and mid-latitudes thanks to climate change is causing weaker polar jet streams and more persistent weather patterns. If this pattern extends further south, could it be that more atmospheric mixing between hemispheres will be the result, and that seasonality will be lost? Could it be that this is an overlooked and understudied potential impact of global climate change?

I took the question to Francis, who is arguably the best-equipped person on the planet to say if this is a valid extension of the ideas presented in her work. Surprise, surprise: She says it’s not. While her work focuses specifically on the polar jet stream and not what’s happening on the equator, there’s no reason to believe more hemispheric mixing will result from climate change, she wrote in an email.

In fact, the opposite may be true. “The polar jet is the one that we expect to weaken in response to a rapidly warming Arctic, as this differential warming will reduce the north-south temperature difference between the Arctic and mid-latitudes, and it’s this temperature difference that fuels the polar jet,” she wrote. “Interestingly, the upper levels of the tropics are also warming faster than are mid-latitudes, which increases the temperature difference between them and the tropics, which leads to a stronger jet. The topic of this article is mixing up the two jets and how they are being affected by greenhouse-gas-induced warming.”

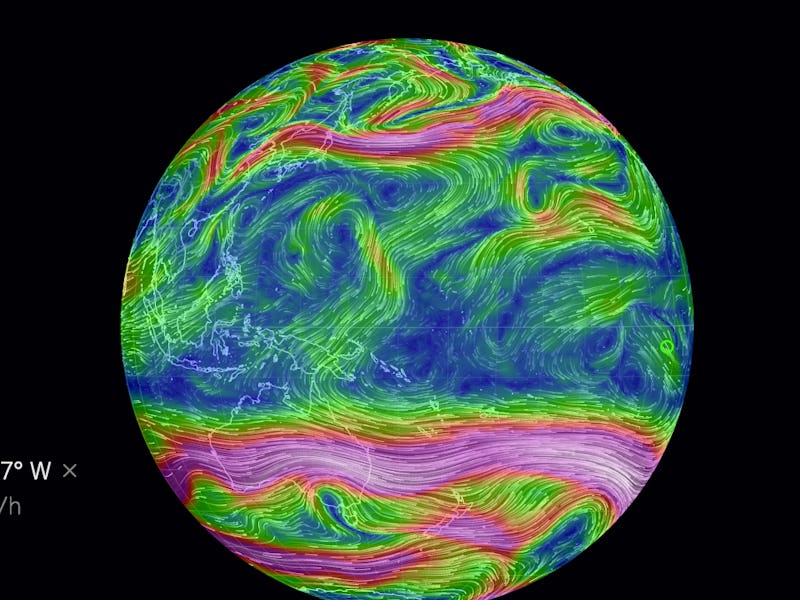

And then there’s this: “When tropical air from the tropics south of the equator mixes with tropical air north of the equator (or visa versa), no big deal — the two air masses have very similar properties,” Francis expanded. Of course. It’s pretty clear from the maps used by Fanney and Beckwith that we’re not looking at a single jet stream running from north to south, but two mostly separate hemispheres with some mixing going on in the middle. Mixing warm air with other warm air only results in more warm air.

Reached by phone, Beckwith stood by his analysis. He said it was a mistake to use the word “unprecedented” in the headline of the video and blog post without qualification — he later added a question mark, to indicate uncertainty about whether or not this pattern has been seen in the past, although his post still asserts that “this is new behaviour.” Of course, it’s not new or unprecedented, as YouTube commenters quickly pointed out with screenshot examples.

Beckwith considers himself a generalist, who looks at the climate system overall rather than specializing in a particular aspect. “The scientific community is pretty much against somebody who looks at the whole system,” he says. “Their argument is that it’s hand-waving.” He criticized the media, too, for relying too heavily on the opinion of specialists, who cannot always see the forest for the trees.

“I’m just talking common sense,” he says. “Because of the huge rise of temperature in the Arctic, the jet streams are getting very distorted.” He points to the lack of a clear distinction between the polar and subtropical jet streams as evidence that things are getting wonky. (Francis says this is normal seasonal variation, since during the summer the temperature differential between the tropics and the mid-latitudes is reduced.)

There’s nothing wrong with being a generalist, but if you’re going to hypothesize about the outcomes of a specific pattern, you should have specific evidence to back up your claim. That’s why journalists lean on specialists to substantiate their positions, even when the argument makes an intuitive sort of sense.

There’s lots of good evidence out there to support the position that we are in a global climate emergency that demands immediate attention and decisive action, but jet streams crossing the equator aren’t among it.