The six human screams

I scream, you scream, but why do we scream?

Why do we scream?

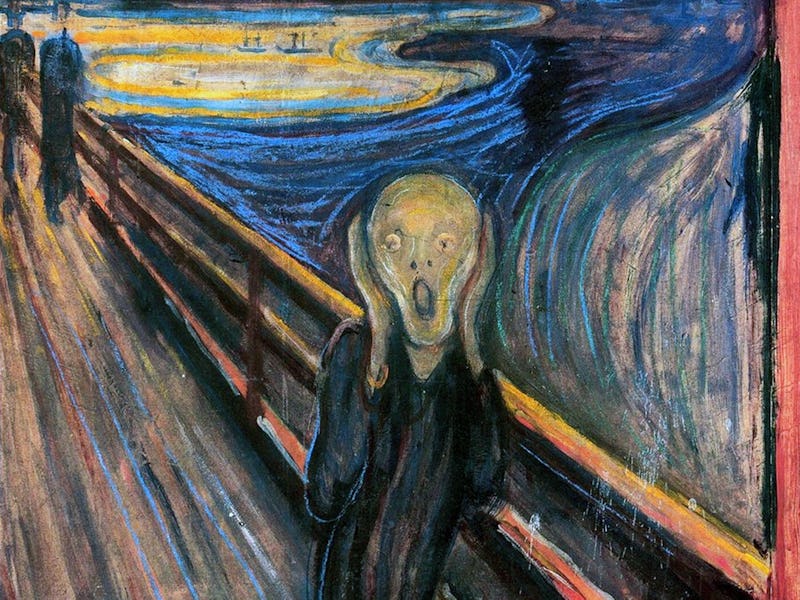

If you think we scream to express fear or aggression, you’re not alone. It was seemingly on the mind of Edvard Munch when he painted the most famous work of art about screaming, “The Scream.” That guy definitely doesn’t look happy.

Meanwhile, in nonhuman primates and other mammals (where screams have been more thoroughly studied) screams are thought to be limited to three categories: alarm, aggression, and fear. Why should we be any different? From an evolutionary biology perspective, humans are nothing more than smart monkeys (and sometimes not even that comparatively smart).

But despite how we commonly think about screams, the human scream is more varied — just think of the difference between a scream after getting a college acceptance letter and a scream on a rollercoaster.

And in a new study, researchers at the University of Zurich classify the different types of screams humans can perceive in other humans. The results, published Tuesday in PloS Biology, offer a surprising find: Humans produce six different types of recognizable screams.

The background — Sascha Frühholz is a professor of Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience at the University of Zurich and the study’s first author. “Only humans seem to scream in ‘non-alarming contexts, but this phenomenon has so far been completely neglected in scientific research,” Frühholz tells Inverse.

Wanting to understand more about the significance of these various types of screams — and how other humans responded to them — Frühholz and his colleagues devised a study.

What they did — The researchers asked twelve participants to imagine themselves in various positive and negative situations, and scream in response. Situations included being attacked in a dark alley, trying to intimidate an opponent, having your favorite team win the World Cup, and experiencing “sexual delight.”

“... this phenomenon has so far been completely neglected in scientific research.”

The researchers recorded these screams and then asked other study participants (not including the screamers) divided into groups to listen to the screams. One group, for example, rated how alarming they found the screams by positioning an indicator between 0 and 1. Screams that weren’t alarming at all would get a zero, very alarming would get a one, everything else was somewhere in between.

Another group of participants was asked to, as quickly as possible, determine what type of scream it was (joyful, fearful, etcetera). Variations on these experiments were repeated, including one where people listened to the screams in an fMRI machine.

What they found — The results revealed six “psycho-acoustically” distinctive types of scream calls. In other words, these are the six types of screams that people heard and assigned meaning to.

According to the study, the six types of screams are those of:

- Pain

- Anger

- Fear

- Pleasure

- Sadness

- Joy

Surprisingly, the “alarm” screams (pain, anger, fear, sadness) were not the screams participants responded to the fastest. Instead, participants were quicker and more accurate in identifying screams of joy and pleasure.

What it means — The data suggests people are more sensitive to positive and non-alarming screams, Frühholz says.

“This partly contradicts previous assumptions about a ‘threat bias’ in human and primate cognition,” he explains.

“Threat bias” is an exaggerated or hyperfocus on potential threats. While a key evolutionary tool — you certainly want to pay attention to threats — too much can create anxiety, making a person focus exclusively on the threat even when there are mitigating factors that might dampen the threat.

The study found “only humans seem to scream out of joy and pleasure.”

The study does still show “humans scream, as many other species would do, and there is a similarity in this screaming voice repertoire that is shared across a broad variety of species and that has a very long evolutionary history,” Frühholz says. There are similarities between how we and other animals vocalize a scream of anger.

But, in addition to the shared vocal repertoire, “screams in humans are much more diversified, and only humans seem to scream out of joy and pleasure,” he adds.

Why it matters — Frühholz says that for decades:

“Research in emotional communication and affective neuroscience assumed that negative emotions and threat signaling has priority for any social interactions. The human brain and especially those parts of the brain that detect emotions [the limbic system] have been described as a ‘threat detector.’”

That’s important. Listeners “need to respond differently to each type of scream,” he adds.

“If approached by a person screaming in anger, you are probably well advised to distance yourself from this person. Contrarily, most humans would approach a person screaming in pain to provide support and help.”

But there has to be more going on — at least when considering joyful or pleasure-induced screams. Otherwise, why would we produce them?

The big takeaway — The answer to why we produce screams in non-alarming situations like when experiencing joy or pleasure, still isn’t completely clear. Frühholz does, however, have a theory.

Given that other animals seem to limit their screams to various types of alarms, he posits that the answer might be found in our complex social environments. It could be that in complex social environments, he says, “positive emotions are much more relevant for the dynamics of social interactions.”

In other words, to thrive in our current environments, we might need more than just the ability to raise the alarm. It could be that expressing pleasure is just as important to our survival.

Abstract: Across many species, scream calls signal the affective significance of events to other agents. Scream calls were often thought to be of generic alarming and fearful nature, to signal potential threats, with instantaneous, involuntary, and accurate recognition by perceivers. However, scream calls are more diverse in their affective signaling nature than being limited to fearfully alarming a threat, and thus the broader sociobiological relevance of various scream types is unclear. Here we used 4 different psychoacoustic, perceptual decisionmaking, and neuroimaging experiments in humans to demonstrate the existence of at least 6 psychoacoustically distinctive types of scream calls of both alarming and non-alarming nature, rather than there being only screams caused by fear or aggression. Second, based on perceptual and processing sensitivity measures for decision-making during scream recognition, we found that alarm screams (with some exceptions) were overall discriminated the worst, were responded to the slowest, and were associated with a lower perceptual sensitivity for their recognition compared with non-alarm screams. Third, the neural processing of alarm compared with non-alarm screams during an implicit processing task elicited only minimal neural signal and connectivity in perceivers, contrary to the frequent assumption of a threat processing bias of the primate neural system. These findings show that scream calls are more diverse in their signaling and communicative nature in humans than previously assumed, and, in contrast to a commonly observed threat processing bias in perceptual discriminations and neural processes, we found that especially non-alarm screams, and positive screams in particular, seem to have higher efficiency in speeded discriminations and the implicit neural processing of various scream types in humans.

This article was originally published on