Researchers: Pump iron for 30 minutes a week to ward off early death

A little goes a long way.

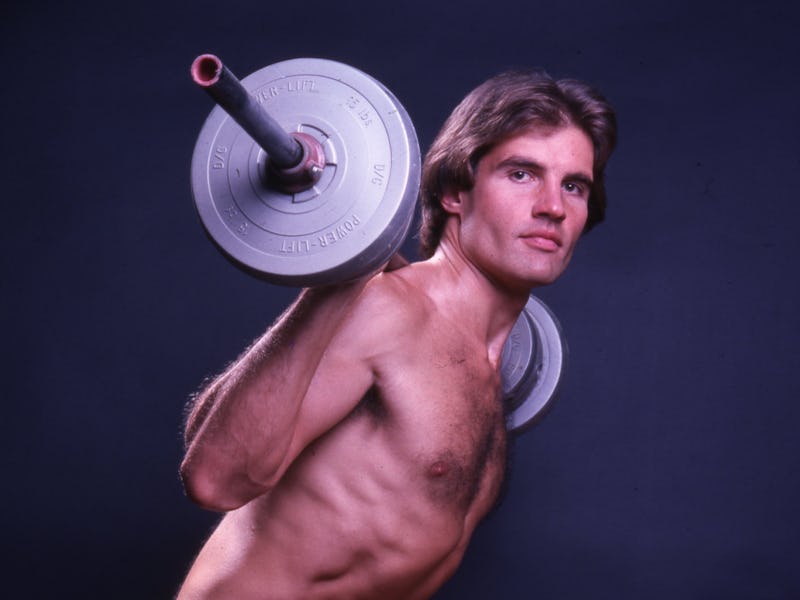

Aerobics, Zumba, HIIT, spin cycling classes: All have two things in common. The first is that they are exercise fads. The second is that they are cardio. As exhausted as you may be after pedaling for 45 minutes like, take note: You have good reason to visit the weight room after the trendy fitness class — even if just for a few minutes. Less than an hour of strength training each week could reduce your risk of dying from one kind of disease by about 15 percent, according to a meta-analysis published this week in The British Journal of Sports Medicine.

What’s New — Researchers at the Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine in Japan scoured databases for studies investigating muscle-strengthening activities and death from non-communicable diseases. A non-communicable disease is an illness you contract neither from another person nor an animal, like heart disease. They found 16 studies that met their criteria.

LONGEVITY HACKS is a regular series from Inverse on the science-backed strategies to live better, healthier, and longer without medicine. Get more in our Hacks index.

After crunching the numbers of seven studies that measured mortalities of any cause relating to a non-communicable chronic condition, the researchers found that strength training for 30-to-60 minutes a week appears to be correlated to a reduction in the risk of death from these conditions by 15 percent.

“Muscle-strengthening epidemiology has only begun”

The meta-analysis was spurred by a revisiting of health recommendations in Japan, lead author Haruki Momma tells Inverse.

“In Japan, a revision of the national physical activity guidelines is underway, and a debate exists regarding whether muscle-strengthening activities should be included,” he explains.

“[W]e tried to support the recommendation from the perspective of preventing premature death and [non-communicable diseases],” he adds.

Momma’s team also investigated incidence (not deaths) of heart disease, diabetes, and cancer and found that between 30 and 60 minutes of muscle training every week is correlated to reduced risks:

- Heart disease: The risk is reduced 17 percent.

- Cancer: The risk is reduced 14 percent.

- Diabetes: The risk is reduced 17 percent.

It’s important to note, however, that once the researchers started to drill down into specific conditions, they had very few studies to base their conclusions on.

In fact, Momma’s team rate the “overall quality” of their own evidence for these micro-results as “very low,” so take the numbers with a hefty pinch of salt.

“I know this is a serious limitation of our findings,” Momma says.

“Although our work may become an early landmark of muscle-strengthening epidemiology, muscle-strengthening epidemiology has only begun.”

Weight lifting has been a sport and a spectacle for decades, practiced at the first modern Olympic games in 1896, but scientific investigation into its benefits is new.

Further, the researchers found no association between strength training and the risk of site-specific cancers, like colon, kidney, bladder, and pancreatic.

Also, the idea that the more time you spend pumping iron the better placed you may be to reduce your risk even more didn’t hold up in this analysis. The researchers found no evidence that weight training for more than an hour a week lowered one’s risk beyond what was seen in the 30-60 minute window. The exception was diabetes: The researchers found that the risk of diabetes dropped lower the more time one spent pumping iron.

Cardio could still play a beneficial role, however. Based on three studies, a weekly regiment of one hour of strength training and two and a half hours of aerobic workouts is correlated to a 40-percent reduction in risk of death from these conditions, according to the paper.

Science in Action — The studies cited in this review are all observational, meaning the researchers tracked the health outcomes of participants over a time span. They ranged in six to 25 years of follow-ups. The smallest study included 3,809 people and the largest 479,856.

Some were drawn from larger “biobanks,” into which volunteers regularly submit a wide range of health data so that researchers can later pick through for correlations.

Calisthenics is one way to practice strength training

All the studies included focus on muscle-strengthening exercises, including weight lifting, resistance training, and calisthenics (like push-ups and chin-ups), but not on everyday chores that exercise the muscles, like carrying heavy loads or doing yardwork.

How This Affects Longevity — The diseases studied are all top causes of fatalities. Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the U.S., killing about 659,000 people a year. Cancer is the second-leading cause, with 602,350 deaths in 2020 (though cancer deaths are declining, thanks to a combination of better treatments and a decline in tobacco usage).

Diabetes has killed more than 100,000 Americans annually in recent years — a rise experts attribute to societal problems that exacerbate type-2 diabetes and diabetes complications, like housing instability and unequal access to healthy foods.

What It’s a Hack — These findings are a noble attempt to quantify the life-extending benefits of strength training, but they come with a lot of caveats.

For a meta-analysis — a study that is supposed to draw broad findings from a lot of studies — there weren’t that many studies to draw on.

“The first and most important limitation is that the meta-analysis included only a small number of studies,” Momma and his co-authors write in the paper.

There is also publication bias. Studies that do not show correlations tend not to get published. (In academia, this is known as the “file drawer problem.”) Meta-analyses, by their nature, only include published studies, so the results may be “overestimated.”

Also, most of the studies cited used self-reports to gauge how much time the participants spent doing weight training. It is entirely possible that people overstate how much time they spend at the bench press.

Further, there are a great many muscle-strengthening activities, and the studies did not account for what the participants actually did when they trained their muscles or how intensely they worked out.

Lastly, most of the studies included in this analysis involved people in the U.S. It’s possible the results don’t apply to other people living elsewhere in the world.

Yet few would argue that a weekly routine of moderate strength training does not make one healthier and, in turn, less likely to die from a chronic condition. There is a consensus that working the muscles increases bone density, helps manage one’s weight, and reduces symptoms of some chronic conditions (including heart disease and diabetes), all of which become increasingly important to take into account as you age.

So, if you are fretting about longevity, go ahead and recover the Bowflex from the attic.

Hack Score — two out of ten repetitions on the leg press 🦵🦵

Abstract:

Objective To quantify the associations between muscle-strengthening activities and the risk of non-communicable diseases and mortality in adults independent of aerobic activities.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies.

Data sources MEDLINE and Embase were searched from inception to June 2021 and the reference lists of all related articles were reviewed.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies Prospective cohort studies that examined the association between muscle-strengthening activities and health outcomes in adults aged ≥18 years without severe health conditions.

Results Sixteen studies met the eligibility criteria. Muscle-strengthening activities were associated with a 10–17% lower risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease (CVD), total cancer, diabetes and lung cancer. No association was found between muscle-strengthening activities and the risk of some site-specific cancers (colon, kidney, bladder and pancreatic cancers). J-shaped associations with the maximum risk reduction (approximately 10–20%) at approximately 30–60 min/week of muscle-strengthening activities were found for all-cause mortality, CVD and total cancer, whereas an L-shaped association showing a large risk reduction at up to 60 min/week of muscle-strengthening activities was observed for diabetes. Combined muscle-strengthening and aerobic activities (versus none) were associated with a lower risk of all-cause, CVD and total cancer mortality.

Conclusion Muscle-strengthening activities were inversely associated with the risk of all-cause mortality and major non-communicable diseases including CVD, total cancer, diabetes and lung cancer; however, the influence of a higher volume of muscle-strengthening activities on all-cause mortality, CVD and total cancer is unclear when considering the observed J-shaped associations.

This article was originally published on