Do vagus nerve exercises help anxiety? Murky science complicates a wellness trend

An explanation of the knotty link between the vagus nerve and mental health.

In Latin, the word for “wandering” is vagus. Appropriately, the vagus nerve is known as the “wandering nerve” because of its long path through the human body. It’s an exciting target in the world of science because an increasing number of studies suggest electrically stimulating it can improve outcomes for people with a range of conditions, from treatment-resistant depression to post-traumatic stress disorder.

The vagus nerve is also a darling of the wellness industry — but this is where things become more complicated. Millions of people watch videos of vagus nerve exercises that promise to “rewire” the brain on social media. The hashtag #vagusnerve has been viewed at least 45.9 million times on TikTok alone. If you search “vagus nerve” on Instagram or Google you’ll find thousands of people claiming the ability to teach you how to live a better life through “resetting” the nerve. In turn, Google Trends shows a steady climb in interest over the past five years in the vagus nerve overall. Yet the science is murky at best.

Scientific evidence for the purported benefits of these vagus nerve exercises, activations, and resets is inconsistent and sparse. However, there are a growing number of studies which do support vagus nerve stimulation via electrical impulses as a treatment for a variety of conditions.

This difficulty in explaining the benefits people experience when following guidance around the vagus nerve may in part be because of confounding influences. What’s taught as exercising the vagus nerve, for example, often involves deep breathing and mindfulness — which studies do show benefits mental health. But it’s difficult to know the exact mechanism that can explain the benefits people experience when they engage with these practices.

“I think it’s fair to say we still have a lot to learn.”

Christa McIntrye is an associate professor at The University of Texas at Dallas and studies the emotional modulation of memory storage. Through her research, she’s found electrically stimulating the vagus nerve promotes memory consolidation and synaptic plasticity, and reduces anxiety. Her work suggests vagus nerve stimulation can enhance treatments for PTSD and anxiety.

She’s also not convinced vagal activity can be controlled through actions like deep breathing. It makes sense in theory, she says, but tells me “it’s not possible to confirm that every time someone does deep breathing, they’re stimulating their vagus nerve in a way that is beneficial.” This is why her team uses direct electrical stimulation.

“Some may be willing to make inferences based on evidence that exercise and deep breathing can have beneficial effects, but I don’t know of any controlled, well-powered studies showing that these effects are mediated by the vagus nerve,” McIntyre says. “I think it would be fair to say we still have a lot to learn.”

What is the vagus nerve?

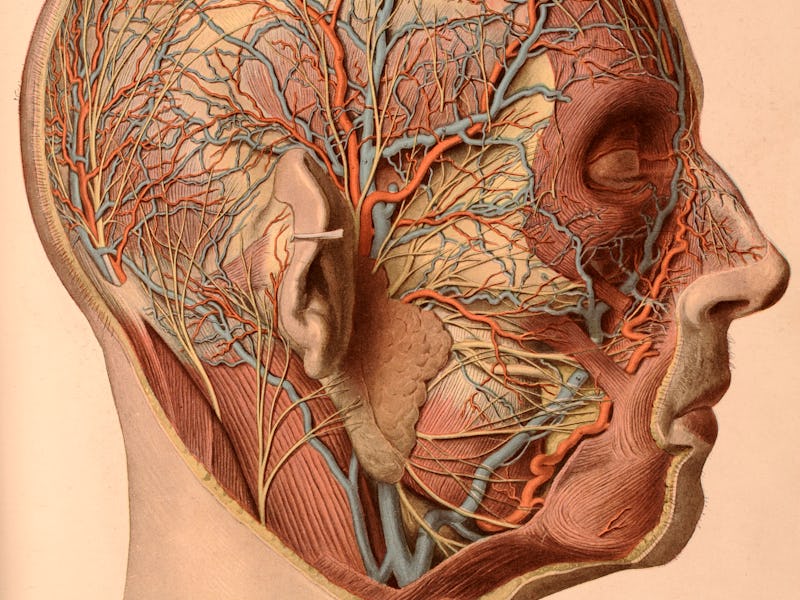

To understand what we do and do not know about the vagus nerve and mental health, we should start by knowing what the vagus nerve is. It is the longest and most complex of the cranial nerves, and runs down both sides of our necks, stretching from the brainstem to the abdomen.

It represents the main component of the parasympathetic nervous system, which controls the body’s rest and digestion response. Accordingly, the vagus nerve helps coordinate the interaction between your breathing and your heart rate, and carries signals from the digestive system to the brain.

The vagus nerve stretches from the brainstem to the abdomen.

“It is what we call a bidirectional nerve, in that it sends information both to and from the brain,” Simon Cork tells me. Cork is an honorary lecturer at Imperial College London and a Senior Lecturer in physiology at Anglia Ruskin University Medical School. He studies the role of the vagus nerve in gut-brain communication.

“Information coming from the brain has effects such as stimulating digestion and reducing heart rate,” Cork says. “Information going to the brain includes things such as blood pressure and nutritional status.”

Can vagus nerve exercises relieve anxiety?

Most vagus nerve exercises involve a variety of gentle movements — like tipping your head to the side and shifting your eyes — and deep breathing. And while these actions may benefit you, it’s not necessarily to do with your ability to activate the vagus nerve, Cork explains.

I asked him to watch a video titled “Vagus Nerve Exercises to Rewire Your Brain From Anxiety.” It’s been watched over 2.7 million times and is just one of a number of vagus nerve-themed videos made by its creator, Sukie Baxter. In the video, Baxter explains how her work is inspired by the book Accessing the Healing Power of the Vagus Nerve, which itself is supported by and inspired by Stephen Porges, a scientist at the Kinsey Institute at Indiana University and a professor of psychiatry at the University of North Carolina.

Porges advocates for and researches the polyvagal theory, which claims a connection between the vagus nerve, emotional regulation, and social connections that can explain how we process trauma. It is both widely cited and embraced by some mental health practitioners, and criticized by some for not being supported by empirical, scientific research. The debate over whether or not it is pseudoscience is quite contentious.

Most vagus nerve exercises involve a variety of gentle movements — like tipping your head to the side and shifting your eyes — and deep breathing.

Beyond that conversation, is a separate debate over what some purveyors of the polyvagal theory say their exercises can and cannot do.

Cork watched the video and found it frustrating. “None of it is based on any scientific basis whatsoever,” he says.

He explains that being in a calm, relaxed state — which these exercises may influence — may induce a reduction in heart rate, which is mediated by the vagus nerve. But “these videos claim that the exercise itself is ‘activating’ the vagus nerve which in turn is causing relaxation,” Cork says. “There is no evidence for this.”

“The neuroscience of mental health conditions is very limited and in most cases, we don’t yet fully understand the neurobiological basis of conditions such as anxiety or depression,” Cork says. “Statements such as ‘rewiring the brain through the magic of neuroplasticity’ tend to be used because they sound scientific, but in reality these statements — in the way they are intended — have no scientific basis.”

Imanuel Lerman, a pain management physician and associate clinical professor at UC San Diego, says “we don’t know yet how deep breathing exercises may or may not cause neuroplasticity” generally and “clearly more work needs to be done to definitively answer that question.”

But he also describes it as “an intriguing question to ask” — in the context of vagus nerve stimulation.

How can vagus nerve stimulation benefit mental health?

Lerman and his team study how vagus nerve stimulation can dampen the sensation of pain; their work suggests the method could be used to lessen the chronic pain associated with PTSD.

Vagus nerve stimulation involves applying electrical impulses to the vagus nerve, either directly or through an indirect non-invasive stimulation.

His lab and others are investigating whether or not this stimulation can help people with PTSD when used in specific ways. Lerman’s group is currently investigating whether or not daily vagus nerve stimulation for one week can improve anxious responses associated with PTSD.

“... vagus nerve stimulation likely decreases anxiety, improves alertness, and perhaps improves cognition.”

Lerman explains that fMRI studies show subjects who undergo vagus nerve stimulation subsequently activate areas in the brainstem important in norepinephrine signaling (norepinephrine acts as a hormone and neurotransmitter). This increase can “increase arousal, attention, reduce reaction time” and this jointly can improve neuroplasticity, he explains.

But for now, the only mental health condition vagus nerve stimulation is FDA approved for is major depressive disorder. Up to 35 percent of people diagnosed with the condition don’t respond to conventional treatments; in 2005 vagus nerve stimulation was approved in an effort to help those with treatment-resistant depression.

Charles Conway is a psychiatry professor at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and has studied how vagus nerve stimulation can provide an antidepressant benefit to people who typically don’t experience relief after other treatments. These effects typically come after many months, he tells me.

“Studies of patients with depression do support that vagus nerve stimulation likely decreases anxiety, improves alertness, and perhaps improves cognition,” Conway says. His own research suggests it can improve quality of life in people with treatment-resistant depression.

Research is conflicting when it comes to proving a link between these sorts of benefits and engaging the vagus nerve beyond vagus nerve stimulation. What is certain? Taking time to relax your body and quiet your mind is critical for mental health. It can serve you to take part in practices that prompt those states — but you may not want to credit the results to the activation of your vagus nerve.

This article was originally published on