"Being infected with anisakis is not a pleasant experience."

Unsettling images and a new study present a cautionary tale for sushi lovers

A new study documents a dramatic rise in a worm that can be transmitted to humans who eat raw or undercooked seafood.

by Emma BetuelThe next time you dig into a sushi dinner, the bougiest of takeout meals, it might be worth stopping to both inspect and savor. According to the results of recent research, the odds of you finding something unexpected inside have gone up astronomically in recent years.

Just like humans who occasionally end up with 5 foot-long tapeworms protruding from their rectums, marine mammals also struggle with parasitic visitors. Dolphins and whales play host to a genus of worms called Anisakis – parasitic nematodes that take shelter in their poop and go on to infect shrimp, fish, and then, more marine mammals in a vicious cycle (or humans who eat them while they're in any of those intermediate hosts). Meanwhile, seals and sea lions tend to be the final destination for a genus called Pseudoterranova, also known as the "cod worm" — a roundworm that can also affect humans who eat undercooked seafood.

According to a new study, between 1967 and 2013, the abundance of anisakids increased 283-fold over that period of time. It turns out there are far more worms in the sea than we thought.

This analysis was published Thursday in the journal Global Change Biology.

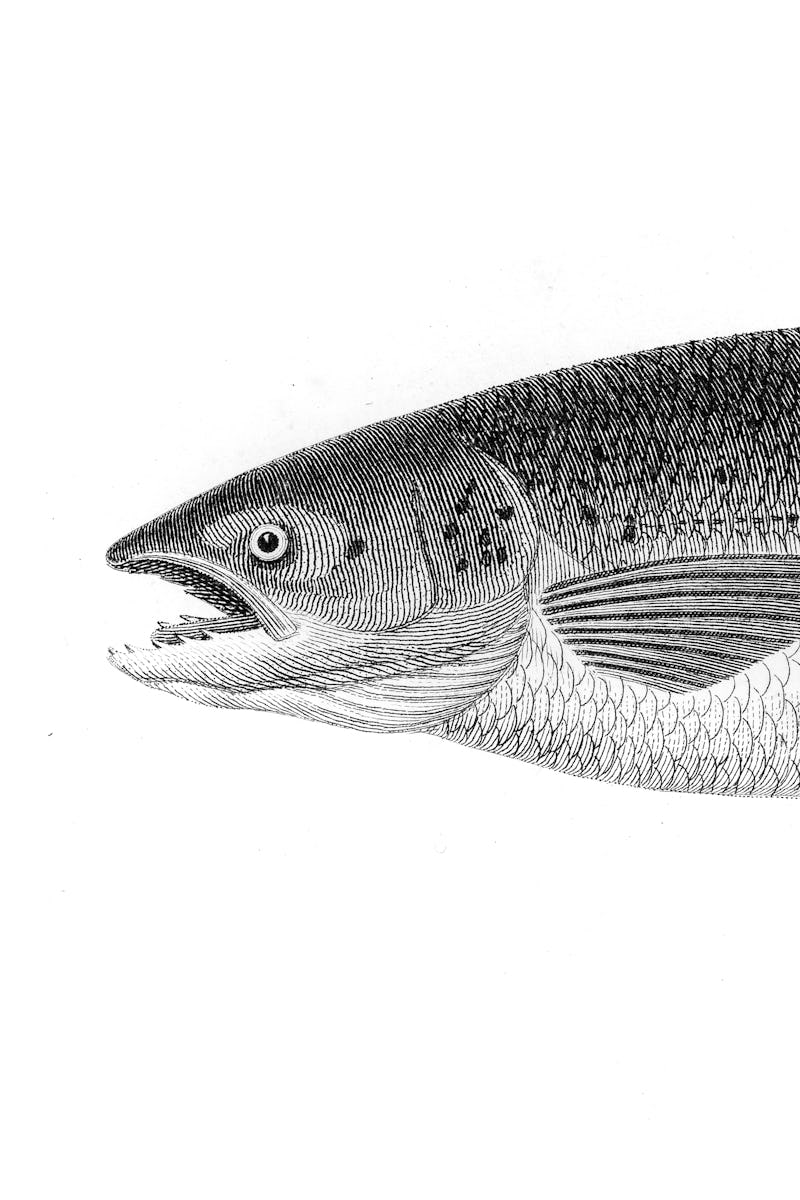

An Anisakis worm is seen in a filet of salmon. These parasitic worms can be up to 2 centimeters in length and are found in the flesh of raw and undercooked fish.

What does this mean for human health?

The study's senior author Chelsea Wood, an assistant professor at the University of Washington, says that, fortunately, there's not a need for sushi-lovers to be too worried.

Sill, when anisakid nematodes (also known as the herring worm) find their way into the human body, they can cause a condition called anisakiasis, which is when the worms attach to the inside of the esophagus, stomach, or intestine.

"They can cause some damage on the way out."

It sounds gross, but Wood tells Inverse that these worms can't survive in human digestive tracts for very long. They can drive an immune response in the intestinal lining — and that can cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain. But especially during the coronavirus pandemic, we have far bigger concerns as far as infections go, she says.

"Being infected with anisakis is not a pleasant experience. Folks who consume live anisakid worms won't suffer long term effects," she says. "But they can cause some damage on the way out."

The more intriguing mystery is why are these worms thriving? The answer may affect the way we feel about our seafood dinners, but also more pressingly, tells us a lot about how life is changing in our oceans for better and worse.

Why so many worms?

Wood's study is a meta-analysis of 123 papers on herring and cod worms that have been published in the past 40 years. Taken together, that work illuminated two stark patterns. The rates of herring worms are skyrocketing, whereas the rates of cod worms haven't increased significantly.

Wood says that it's basically impossible to tease apart why one worm seems to be thriving while the other isn't. But as far as the rise of the herring worms, the ones that more often go on to affect people, she has three preliminary explanations.

"It's hard to wrap your head around – that a 283-fold increase in this gross parasite is a sign that the ecosystem is doing well."

One is actually tinged with good news. The period this study was conducted in actually overlaps "directly" with marine mammal protection legislation like the Marine Mammal Protection Act, says Wood. Sparing host mammals from exploitation and unnecessary slaughter gives parasites more places to thrive.

Anisakis worms in blue whiting fish. The prevalence of these worms, found in raw or undercooked fish, has increased dramatically since the 1970s.

"It's hard to wrap your head around – that a 283-fold increase in this gross parasites is a sign that the ecosystem is doing well," she says. "But parasites are dependent on hosts, and if their hosts are doing well, then their parasites are going to do well."

But there are two competing explanations, that position the situation more negatively: As ocean temperatures rise due to the climate crisis, some parasites are going extinct. The worms examined here may just be reproducing faster, leading to bigger parasitic families that may still die off sooner rather than later.

It's also possible that human nutrient pollution could also be spurring them on. As agricultural, logging or development runoff finds its way into the ocean, it brings with it nutrients, says Wood. This may be setting off a vicious cycle: Those nutrients fuel the growth of phytoplankton (tiny plants), which feed tiny crustaceans, who serve as additional hosts for tiny parasitic worms.

What this means for dinner

Regardless of how and why Anisakis worms have thrived in the past decades, humans will likely do just fine. As Wood notes in a statement, most sushi chefs are trained to catch such worms in raw fish. And if you're worried a bit of closer inspection can't hurt.

Even if you do contract a worm, the result isn't threatening to your health, adds Wood — despite how uncomfortable you might become. The human body can get rid of worms eventually: The CDC notes many people "can often extract the worm manually from their mouth or cough up the worm and prevent infection."

Vomiting, while not very fun, may also expel the worm from your insides.

Unfortunately, marine mammals aren't so lucky. These worms can stick around in their bodies and reproduce, says Wood. We know that when worms linger in human stomachs, they can cause issues like cognitive impairment. But we don't know how this might play out in marine mammals, says Wood, though there could be risks to their health that we don't know about yet.

"There's a potential for a huge health burden on whales and dolphins that are infected," Wood explains.

In summary: Humans may breathe a sigh of relief regarding the safety of eating a sushi dinner. But for those marine mammals who live raw fish each and every day, we're not sure of what their increasingly-wormy future might hold.

Abstract: The Anthropocene has brought substantial change to ocean ecosystems, but whether this age will bring more or less marine disease is unknown. In recent years, the accelerating tempo of epizootic and zoonotic disease events has made it seem as if disease is on the rise. Is this apparent increase in disease due to increased observation and sampling effort, or to an actual rise in the abundance of parasites and pathogens? We examined the literature to track long-term change in the abundance of two parasitic nematode genera with zoonotic potential Anisakis spp. and Pseudoterranova spp. These anisakid nematodes cause the disease anisakidosis and are transmitted to humans in undercooked and raw marine seafood. A total of 123 papers published between 1967 and 2017 met our criteria for inclusion, from which we extracted 755 host–parasite–location–year combinations. Of these, 69.7% concerned Anisakis spp. and 30.3% focused on Pseudoterranova spp. Meta-regression revealed an increase in Anisakis spp. abundance (average number of worms / fish) over a 53-year period from 1962 to 2015 and no significant change in Pseudoterranova spp. abundance over a 37-year period from 1978 to 2015. Standardizing changes to the period of 1978 to 2015, so that results are comparable between genera, we detected a significant 283-fold increase in Anisakis spp. abundance and no change in abundance of Pseudoterranova spp. This increase in Anisakis spp. abundance may have implications for human health, marine mammal health, and fisheries profitability.