Study pinpoints a crucial link between stress and fat

New research adds to our understanding of why stress can make people sick.

When people experience a stressful event they experience a fight-or-flight response. This involves a series of physiological shifts that help them meet the attack or run away.

Generally, hormones released during this evolutionarily embedded response like adrenaline and cortisol tamp down inflammation. However, if stress suppresses inflammation, why does stress also make inflammatory diseases like diabetes and autoimmune disease worse?

For years, scientists have been puzzled by this bodily paradox, unable to pin down the link between stress and inflammatory disease. We've known stress can make a range of diseases worse, but we haven't pinpointed the underlying mechanisms.

In a new study, scientists discovered a crucial player in this process: an immune cell called cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6). They determined that stressful events can induce IL-6 in the body's brown fat cells, triggering inflammation and worsening existing inflammatory responses.

This finding was published Tuesday in the journal Cell.

Researchers think elevated IL-6, which can linger for hours, causes "flare-ups" of inflammatory disease linked to stress. At the same time, IL-6 isn't all bad: The researchers also found that IL-6 prompts the body to increase its production of glucose, in turn fueling the body with energy in anticipation of threats.

Although the research was conducted primarily in mice, these findings also help scientists better understand how stress makes people sick.

It also points to potential strategies to buffer IL-6's inflammatory effects: The team was able to disrupt IL-6's inflammatory effect in brown fat. When researchers blocked signals from the brain to brown fat cells, stressful events no longer worsened inflammatory responses.

Stress test —To better understand how stress influences inflammation and in turn, disease, researchers put the mice under acute stress by restraining them in tubes, switching them into different cages, and socially isolating them. All of these stressful conditions induced high levels of circulating IL-6.

When the researchers surveyed other stress effects they also found 32 inflammatory cytokines and chemokines induced from stress. But IL-6 was the most common and most highly induced.

After the stressful events, IL-6 was significantly increased in blood for two hours, peaked at four hours, and was detected above baseline 18 hours after the stressful event was over. This finding suggests IL-6 may be involved in long term impacts on disease because its levels are elevated for sustained periods of time.

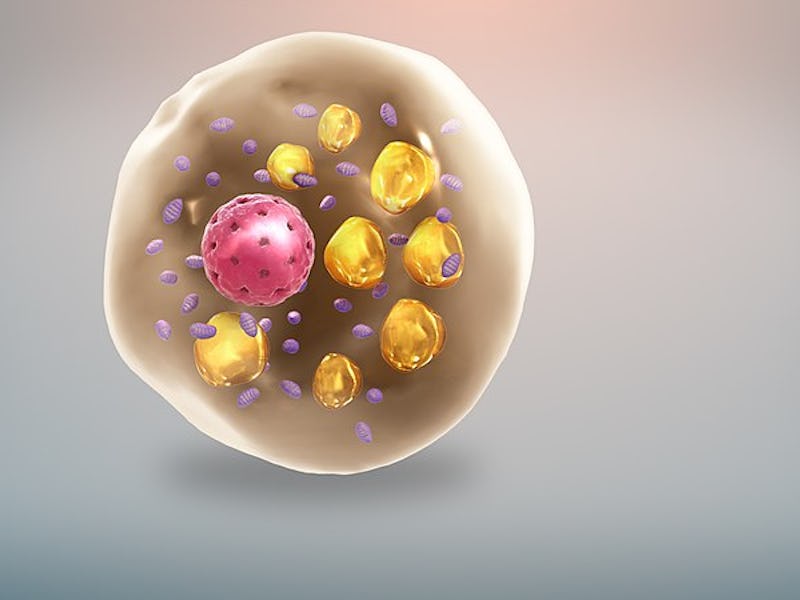

Interestingly, the team found IL-6's production occurred in one surprising place: brown fat cells. Brown fat is primarily known for regulating metabolism and body temperature, so this pivotal role in driving inflammation was unexpected to researchers.

When the researchers blocked IL-6 production and disrupted signals between the mice brains and brown fat cells, the stressed-out mice became less agitated when placed in a stressful environment. They also avoided the spike in inflammation.

This finding suggests if IL-6 is confirmed to drive inflammation and disease in people, not just mice, physicians may be able to reverse this potentially harmful effect.

Indeed, preliminary evidence shows IL-6 may be involved in autoimmune diseases, diabetes, obesity, and mental health disorders like anxiety and depression. The new study suggests existing drugs, which block the activity of IL-6 and typically treat autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, could help alleviate some of these other health issues.

Abstract: Acute psychological stress has long been known to decrease host fitness to inflammation in a wide variety of diseases, but how this occurs is incompletely understood. Using mouse models, we show that IL6 is the dominant cytokine inducible upon acute stress alone. Stress-inducible IL6 is produced from brown adipocytes in a beta-3-adrenergic-receptor-dependent fashion. During stress, endocrine IL6 is the required instructive signal for mediating hyperglycemia through hepatic gluconeogenesis, which is necessary for anticipating and fueling “fight or flight” responses. This adaptation came at the cost of enhancing mortality to a subsequent inflammatory challenge. These findings provide a mechanistic understanding of the ontogeny and adaptive purpose of IL6 as a bona fide stress hormone coordinating system immunometabolic reprogramming. This brain-brown fat-liver axis may provide new insights into brown adipose tissue as a stress-responsive endocrine organ and mechanistic insight into targeting this axis in the treatment of inflammatory and neuropsychiatric diseases.