Inside the global social media movement that claims it changed the CDC's mind on masks

A viral image and a series of intertwining online groups are winning over policymakers.

Writer Leslie Schrock went to a grocery store recently in Tahoe, California, wearing a homemade mask. "I've been watching people give me crazy looks for months," she tells Inverse. But that day, something changed.

A woman, not wearing a mask, approached Schrock at the store. "She said, 'I have a mask in my car, but I was looking in the store and wasn't seeing anyone wearing one. But now that I see you wearing one, I realize it's silly that I'm not wearing one."

The woman isn't the first Schrock has convinced to wear a mask. Likely, she has convinced many more she may never encounter.

Schrock is part of a series of interconnected pro-mask movements that stretch from the United States to Czechoslovakia. Since March, they've had the ear of national governments and the World Health Organization.

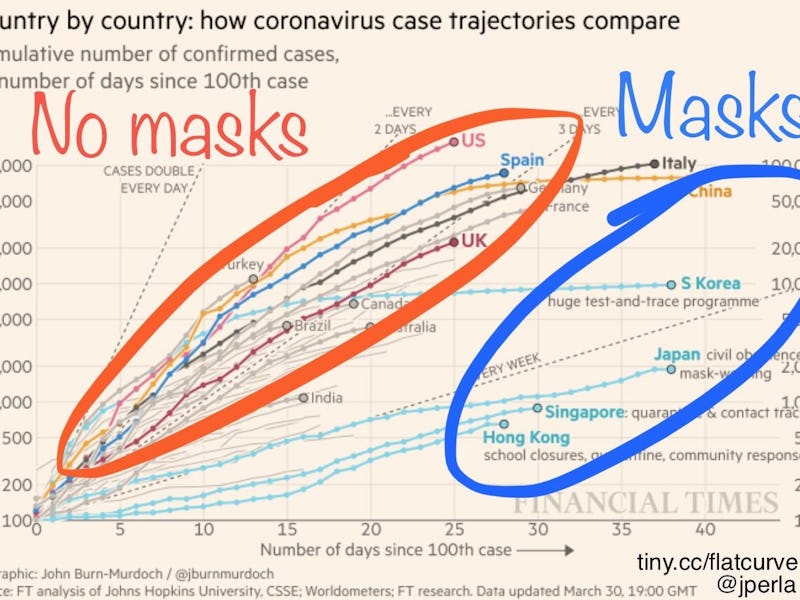

They are likely why, now, you wear a mask you've fashioned from an old t-shirt or bandana each time you leave your home — when, only weeks ago, you probably didn't. Their success, in part, stems from a viral graphic with a climbing line, a bold red circle, and a message that connects the two: "no masks."

This graphic is a visual calling card for the movement, elevating their message and making their goal instantly recognizable. These factors, experts say, are crucial to going viral — at least, the type of virality you want in 2020. Like seeing a screenshot of the Ice Bucket Challenge, or Rosie the Riveter, the "no masks" graphic triggers automatic understanding. That understanding, in turn, can drive decision making.

On April 3, the CDC reversed course on the use of masks and endorsed the use of "cloth face coverings" in public settings where it is difficult to maintain social distancing. For Americans, this was an abrupt change. On March 28, Surgeon General Jerome Adams tweeted that his office "consistently recommended against the general public wearing masks."

This reverse in policy didn't surprise Schrock. She helps manage a site that teaches people how to make their own masks, alongside her father-in-law, Christian Schrock, an infectious disease physician. Both Schrocks are also members of the "Curve Crushers" Facebook group: 246 users who are connected to a larger pro-mask movement that's mobilized over social media.

The first on the Curve Crushers' list of commandments: "Put on a mask before heading outside."

Perla's viral graphic.

You probably haven't heard of the Curve Crushers, but you are connected to them. They are who first posted the doctored Financial Times graphic that compares coronavirus cases in countries with masks to cases in those without. It has since been shared by science reporters and the mayor of Medellín, Colombia. It appears in French news reports and on national television in Tunisia. It's seemingly, everywhere.

It's also definitely not a perfect example of biostatistics. It wasn't even made by a scientist but rather, by Joseph Perla, an author, former Lyft employee, and the admin of the Curve Crushers. Still, it has become a symbol of the pro-mask movement on social media, Perla tells Inverse.

"I thought it was interesting how it kind of took on a life of its own," he says.

The pro-mask movement spans far beyond Perla and the Curve Crushers. The graphic that began with them has taken on a life of its own, shared across the internet; fueling a movement. And now, you can actually buy a face mask with the graphic printed on it.

"None of the world would be able to do what is being done now in this kind of terrible emergency, these dark times unless we had social media," Schrock, the physician, tells Inverse.

The power of an image

Importantly, this graphic can't actually prove the efficacy of mask-wearing. A number of reasons, ranging from mass-testing to different responses to the virus, could explain the discrepancy between coronavirus cases per country.

Instead, the graphic is shorthand for a message that scientists have now adopted: masks work.

Julie Wiest is a sociologist who studies culture and media. She tells Inverse that there is a certain power to something that simple, and instantly recognizable across platforms like Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook (Interestingly, this graph was censored by Facebook, tagged as "partially misleading" according to Curve Crushers' Facebook posts.)

"It was easy to understand no matter what platform," Wiest says of the graph. "I think in today’s new media landscapes, images are a really good way to do that."

As a comparison, she says to think about the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge that likely dominated your Instagram feed in 2014. The message is clear, it has a hashtag that can live on multiple platforms, and you instantly know what cause is being promoted the second you see the video.

This graph is successful in similar ways, explains Wiest. The cause is clear and it rapidly spread across platforms — importantly, because Perla made sure that spread happened, spending money on Twitter ads that targeted New York and Washington D.C. These are "centers of power," he says. He claims these ads generated "one two or three million impressions."

"I wanted to have more people who might know people in the government on the East Coast, people who might know people at the CDC," Perla reasons.

Perla's instinct was right: The graphic reached people with the resources to make it take off. It specifically reached Jeremy Howard, an Australian data scientist with 98,000 Twitter followers. He's the co-founder of a pro-mask movement known by the hashtag #Masks4all. (Inverse repeatedly requested comment from Howard for this story but couldn't reach him.)

Howard, and the website behind his movement, takes credit for sparking the CDC's interest in changing mask policy. He is also the author of a Washington Post op-ed on face masks that surged to #1 on Apple News a week before the CDC changed its policy. Perla's graphic is now displayed prominently on the #Masks4all site and is regularly used in videos where Howard argues for mask use.

#Masks4all's adoption of the graphic meant that soon other like-minded online movements started to use the graphic too. The message was clear, and banner to rally behind. Now, these movements are taking credit for changing mask policies around the world — and there's evidence to suggest that, in some countries, they may be right.

How the mask movement went viral

Wiest explains that, while a successful social media campaign has to include a few key ingredients, it all really boils down to one crucial factor: reach has to go beyond those in an immediate circle.

Hashtags help, she says, but "there needs to be a ready-made audience or it needs to get some sort of major attention in some way." Ideally, one movement can connect with another that shares their passion.

In this case, Howard served this purpose. His #Masks4all was a gateway to other mask movements around the world, including one in the Czech Republic, where wearing masks has subsequently become mandatory. That movement is headed by Howard's #Masks4all cofounder Petr Ludwig (who also helped Howard write the pro-masks Op-ed in The Washington Post).

"We got the support of the local government and the support of the Minister of Health," Ludwig tells Inverse. "We are trying to push other governments around the world to make masks mandatory."

Ludwig's day job is also not a scientist but the CEO of a company that helps people "overcome" procrastination. Like Perla, Ludwig is a mask advocate who has gone all-in on mass mobilization on the internet. Also like Perla, Ludwig is a fan of boiling down the scientific debate around masks into easily shareable graphics.

His weapon of choice is Youtube: Ludwig is the creator of a Youtube video that implores people around the world to wear masks, which, as of writing had over 500,000 views.

With Howard's aid, Ludwig helped orchestrate a social media storm that snowballed just a week before the CDC changed its mask policy: On March 28, Howard's op-ed was published and by March 29 it was trending on Apple News. That same day, the Prime minister of the Czech Republic Andrej Babis tweeted Ludwig's video at President Trump, offering this advice: "try tackling virus the Czech way."

Ludwig argues that these steps, alongside Howard's op-ed, helped legitimize the idea of masks in the United States.

"We know that Jeremy’s article was probably the beginning of the CDC's reconsideration because it went viral," Ludwig says.

And arguably, this sequence of events does check off three of the boxes outlined by Wiest: major outside attention, connecting with another movement; the ability to resonate with a ready-made audience. When those boxes are checked, movements do tend to take off, she says.

What's next for the mask movement?

The Czech government is now an active member of Ludwig's campaign. Czech health minister Adam Vojtěch even appears at the end of video Ludwig made, recommending that all countries encourage the use of homemade masks for the public.

"Today we see it is one of the most important decisions we have made," Vojtěch says.

Today, #Masks4all has a platform for its message that can reach millions — and Perla's graphic remains its calling card. Other smaller movements are being brought into the fold.

In Germany, a similar movement is called #Maskauf (roughly translated to "mask on"). One of its leaders is Friedemann Karig, a German author who is in contact with Ludwig.

Karig tells Inverse that he's been in contact with major German social media influencers who are using his hashtag and promoting mask use. German officials have since tweaked their recommendations, suggesting that masks do protect the wearer from spreading the coronavirus. He also, to no surprise, shares the graphic.

"I was like, if I could convince five or ten people with a certain reach on Instagram or something, maybe they could convince the rest of the public," he tells Inverse. "I wasn't sure I was on the right track, but it turned out to be a thing that many people were thinking about but they weren't connected to each other."

Now #Maskauf is launching websites translated into Spanish, French, English, Arabic, Farsi, and Hindi — the goal being to "reach out to 2.5 billion people next week."

For his part, Ludwig wants to do more than spread #Mask4alls's message country by country. On March 27, he placed the details of his pro-mask movement into an email and sent it off to executives at the World Health Organization.

"We have contacts with local executives, European executives and top executives from Geneva," Ludwig says. "We are pushing them from three sides."

The World Health Organization hasn't officially recommended the use of masks for all — yet. But the door is cracking open. On April 3 Mike Ryan, the Director of the World Health Organization's Emergencies Programme, said that as long as masks are saved for healthcare workers, covering the face "in itself is not a bad idea."

"I think they will reconsider their guidelines," says Ludwig. "There’s such an overwhelming body of evidence."