Scientists untangle a critical link between body image and the senses

Manipulating the senses could pave the way toward better body image.

When you look in the mirror, who do you see?

What you see is defined by your ability to be self-aware — an ability shared by some nonhumans, like chimps and perhaps dolphins, that becomes obvious in infants at about 18 months. Who you see, however, is something quite different and a bit metaphysical: a concept of self defined by personal opinion but sculpted through other’s reactions to us.

Your self-image, scientists argued at the 179th Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America on Friday, can also be manipulated by sound and smell. Manipulating these senses can change how one perceives their own body, research suggests, and further research on this manipulation could lead to therapies for people with body perception disorders and wearable technologies that could improve self-esteem.

Lead researcher Giada Brianza, a Ph.D. student at the University of Sussex, tells Inverse her team can envision “future scenarios where new therapies exploiting multisensory stimulations can stand side-by-side with current treatments.” In practice, this could look like olfactory stimulations inside garments, or auditory stimuli in fitting rooms — environments where body awareness is high and a certain sound or smell could cue one to think better of themselves.

"We humans are basically senses."

It’s a confluence of old ideas and new technology. Even Aristotle was thinking about the power of our senses combined together, Brianza says. Now, because of innovations like virtual reality and wearables, our knowledge about multisensory stimuli and how this congruence can affect the psyche has grown. What will come next is the transformation of all of this knowledge into actual aids.

“I am confident that soon we will be able to understand the neuroanatomy behind our senses, especially smell, and we will use the power of multisensory in combination with more and more accurate technologies to meaningfully impact people’s well-being,” Brianza says.

“Not only in a clinical trial but also in daily life.”

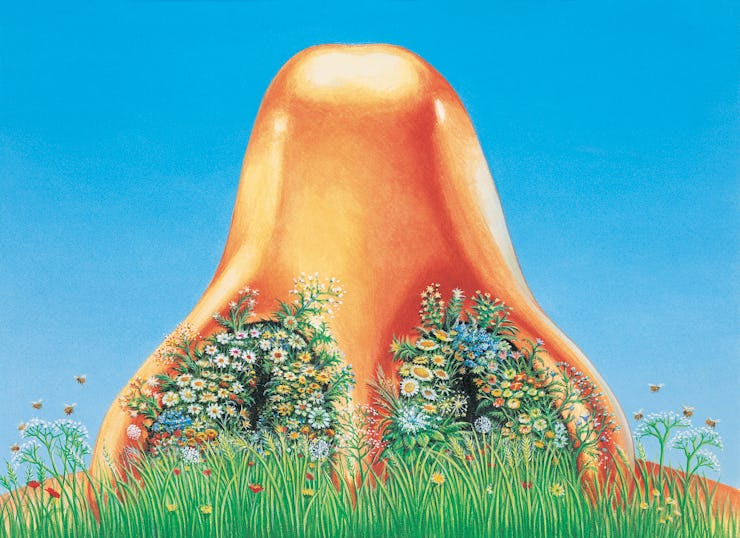

The experiment — The research presented Friday builds off a 2019 study in which Brianza and her colleagues found the scent of lemon could improve how people feel about their body image. During the experiment, participants were asked to adjust the size of a 3D avatar according to their perception of self. A lemon scent resulted in participants feeling lighter; a vanilla scent, heavier.

This was amplified when sound was incorporated. The scientists also recorded the sounds of the participant’s footsteps. When they played the recordings back to the participants at a higher pitch — so more stiletto tap than boot fall — the participants reported, again, that they felt lighter.

Manipulating sounds and smell can change how one feels about their body, scientists found.

“We based our study on the concept of crossmodal correspondences, which is the spontaneous and unconscious association between different sensory stimulations [like when people see colors when they listen to music],” Brianza says.

“It is known that lemon, for example, is commonly associated with spiky shapes and high pitch sounds. Vanilla, on the contrary, with rounded shapes and low pitch sounds.”

The why — These results are likely a response to the brain updating its perception of the body. Human survival, in part, is because the brain evolved to hold several mental models of body appearance, Brianza explains. These are updated in response to sensory inputs. In this case, smell and hearing.

These influence how we feel about ourselves emotionally. The 2019 experiment suggests sound strongly affects unconscious behavior, while scent affects conscious behavior. Both results are paired with the possibility of new ways of combating negative body perception, or even misconception, sometimes characterized as body dysmorphic disorder. A negative view of self is associated with an elevated risk of mental disease, isolation, and eating disorders.

“We humans are basically senses,” Brianza says. “Our perception of reality is possible thanks to our senses. But not only: Our conception and consciousness, as well, are strictly connected with our senses.”

There are still so many mental health questions that psychological handbooks can’t answer, and so many issues that hinder successful treatments, she says. Perhaps this area of research can help; perhaps, in the future, ambient scents in combination with ambient sounds can flow through urban landscapes, boosting well-being. That’s the future Brianza and her team are eager to create.

This article was originally published on