How the next generation of cheaper, better tests could change Covid-19's future

The benefits and risks of rapid diagnostic testing, explained by experts.

In order to track, slow, and ultimately, curb Covid-19's insidious spread, public health officials say we need to test large swaths of the population, fast. However, the road to scaling up testing across the United States has been bumpy a one littered with supply shortages, testing lags, and overburdened labs.

To alleviate this "testing crisis," scientists have developed a cheap, quick approach: rapid diagnostic tests (RDT), which operate as simply as a pregnancy test. These tests, which detect SARS-CoV-2's viral proteins or antigens, have about 84 to 97.6 percent sensitivity compared to RT-PCR, the gold-standard of coronavirus testing.

But what RDTs miss in accuracy, some argue they make up in simplicity, cost, and convenience. These tests cut the turnaround time for results from days to minutes, at a fraction of the price. These near-real-time results can, in turn, enable people to self-isolate faster if they test positive, and quickly notify those they've been in contact with.

While RDTs are no magic bullet, if deployed on a massive scale with appropriate infrastructure and clinical guidance, some experts argue they could speed up testing and contact tracing, while reducing the strain felt by overloaded testing labs. In the race to catch up to Covid-19's swift spread, RDTs could be a key tactic to get ahead.

"Right now, many more folks have access to tests, but the results are too slow to be of practical use," Matthew Ferrari, an epidemiologist and public health expert at Penn State, tells Inverse. "I think we need to first speed up our existing processes to help contact tracers get ahead of infections rather than chasing behind."

RDTs can help the health system by rapidly triaging patients and increasing the chances that slower and more expensive diagnostics are reserved for those that are most likely to be positive, Ferrari adds.

A box containing the Covid-19 test from Abbott Laboratories, pictured during a White House briefing.

"RDTs could be a sea change in the way we do things, and paired with the correct infrastructure, could have big impacts on both Covid-19 and the future of telehealth in general," Ferrari says.

Joseph Petrosino, the chair of virology and microbiology at Baylor College of Medicine, echoes Ferrari's hope that RDTs will change the testing game — if they are deployed carefully and are clinically validated for accuracy.

"Being able to get test results more quickly will speed up the response in isolating exposed individuals and thus more quickly shut down virus spread," Petrosino adds.

Faster testing is desperately needed because, in addition to wearing masks, social distancing, and washing hands, testing is a "critical component of getting rid of SARS-CoV-2 in the shorter term," Petrosino explains.

"Without it, we don’t know where the virus is and who is spreading it, which leaves almost zero chance of stopping it. Waiting for herd immunity, either through exposure and/or vaccination, is a dangerous gamble that will cost countless lives unnecessarily," Petrosino says.

How do rapid diagnostic tests work?

Diagnostic coronavirus tests detect if people have an active Covid-19 infection and should take steps to quarantine or self-isolate from others. There are two types of diagnostic tests:

- Molecular tests like the RT-PCR tests, which detect the virus's genetic material

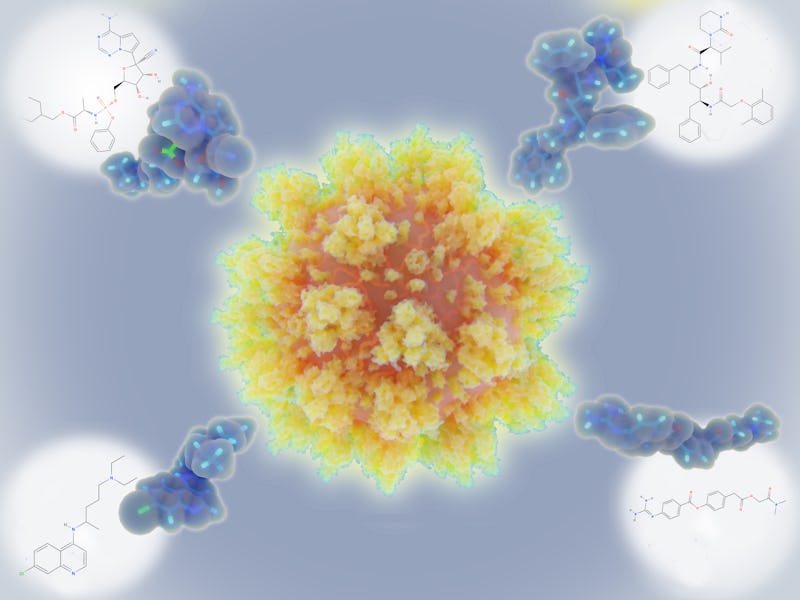

- Antigen tests, or RDTs, that detect specific proteins called antigens on the surface of the virus.

Both tests require a nasal or throat swab, although RT-PCRs tend to go higher up into the nasal cavity. These are the infamous tests that people liken to getting their brains tickled with a nasal swab.

RDTs offer some key practical advantages over molecular tests: They're cheaper, easier to use, and give clinicians and test-takers critical info quickly. When taking a RT-PCR test, people typically wait days, if not a week or more, for results, because their samples need to be sent to and handled by specialized technicians in centralized labs. RDT results are processed on the spot and come back within the hour.

But the major drawback of RDTs, for now, is accuracy. RT-PCR tests can detect Covid-19 infections with near 100 percent accuracy, and can definitively rule out an active Covid-19 infection. Meanwhile, RDTs tend to have a 10 to 20 percent false-negative rate.

If RDTs miss someone's active infection and result in a false negative, that person can go out with a false sense of security, mingle with others, and unwittingly spread the virus. But at the same time, people may do the same as they wait for RT-PCR results.

That's why if someone tests negative via an RDT but still shows Covid-19 symptoms, some health care providers may order another RDT or RT-PCR test 24 hours later to validate results.

"Highly accurate tests are ideal, but we know that the tests with the greatest accuracy are molecular tests and involve nasopharyngeal sampling, which takes time, are more expensive and involve a sampling method that is uncomfortable," Petrosino says.

He argues that waiting to use rapid diagnostic tests on a larger scale until they are perfect "will have us waiting a long time." That wait, Petrosino says, can "lead to the virus being here a lot longer than needed."

The next generation of rapid diagnostic tests:

Weighing these factors, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recently gave an emergency use authorization to Abbott Laboratories, a company that developed a $5, 15 minute Covid-19 rapid diagnostic test. They also committed 70 million dollars to purchasing 150 million RDTs from Abbott Laboratories.

According to FDA, the Abbott test correctly identifies patients with SARS-CoV-2 97.1 percent of the time and people without the virus 98.5 percent of the time.

"No one thing, an RDT or a vaccine, will get us out of this."

Ferrari says this move is a "huge deal," jumping a pivotal regulatory hurdle and helping clinicians validate the accuracy and utility of RDTs. The amount of testing in the US that is needed is in the 100 million to 500 million tests per month range (accounting for repeat testing needs), Petrosino explains.

"With the advent of the new Abbott RDT, and others like it, this number should be achievable within the next three to six months perhaps," Petrosino says.

"In the clinic setting, RDTs could help to rapidly triage patients, reducing demand on the slower and more expensive gold-standard diagnostics," Ferrari predicts. "Paired with telehealth and safety-nets for those who test positive, RDTs could be hugely helpful in the home."

However, Ferrari stresses their impact on their own will be limited without a good, safe mechanism for communicating results to a clinician, and mechanisms to allow individuals who test positive to act upon those results.

Ferrari suggests self-reporting positive and negative results, as well as self notifying contacts where exposure could have taken place. Petrosino notes that Abbott offers a user-friendly app that can help people communicate test results to work or school officials.

"RDTs can reduce strain on otherwise burdened lab systems and can trigger individuals to stay home if there are social safety nets at work and school to support their doing so," Ferrari explains. These safety nets include staying home from work without lost wages or staying home from school without falling behind.

"No one thing, an RDT or a vaccine, will get us out of this. Magic bullets only happen in the movies," he adds.

"New technologies like this need to be worked into a system of production, distribution, education, and downstream care in order for them to work."

How to get a rapid diagnostic test:

Currently, RDTs are available primarily for health care providers in clinical testing sites — urgent care facilities, mobile testing sites, and doctors' offices. On Thursday, scientists announced that a 90-minuted RDT currently being used in London hospitals is at over 94 percent sensitivity and 100 percent specificity. The UK government has placed an order for 5.8 million of these testing kits.

There is a small but increasing number of at-home RDTs, but RT-PCR tests continue to be the most common testing methods for active infections.

Petrosino predicts a near-future where RDTs are sold directly to schools or surveillance programs, and sold over the counter, directly to consumers. This could happen in the next three to six months once RDTs are validated in broader laboratory settings currently underway, Petrosino says.

For now, people who hope to be tested a single time to verify whether or not they have been exposed should undergo the gold-standard RT-PCR test, he advises, because of its accuracy.