A newly discovered HIV variant is a cautionary tale for Covid-19

“We should never underestimate the potential for viral evolution.”

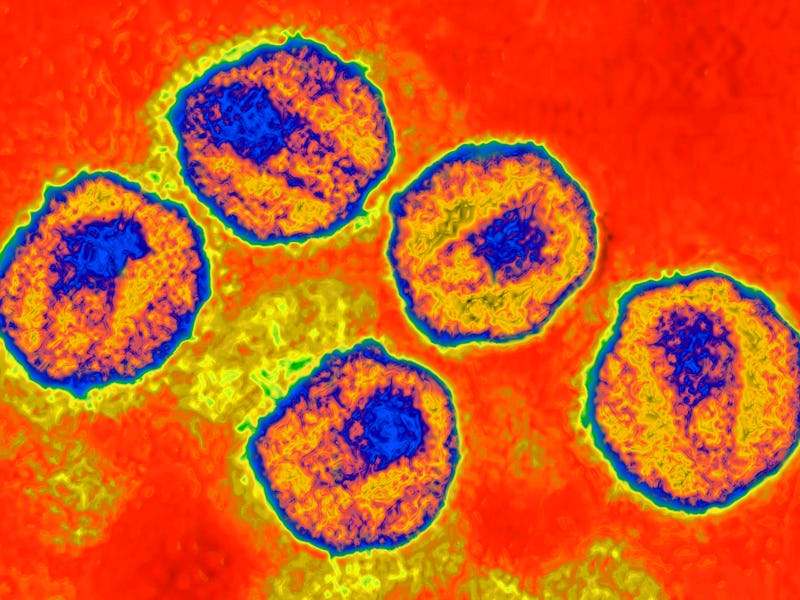

A newly discovered, highly virulent variant of the HIV virus should serve as a cautionary tale about the future of Covid-19, researchers say. The finding, revealed Thursday in the journal Science, is a reminder that we can’t be certain of how any highly transmissible virus will evolve.

What’s new — In a study, scientists report the discovery of a more virulent variant of HIV that’s circulated in the Netherlands for the last decade. It offers a sobering reminder of the power of viruses to change — and not always to the benefit of human health.

As the Omicron variant of Covid-19 sweeps the globe, the evidence thus far suggests that it’s significantly more transmissible than the original SARS-CoV-2 virus, but it likely causes less severe disease.

Viruses often evolve to become more transmissible but less deadly. A popular, anthropomorphized explanation is that viruses want to replicate, so evolving to infect more people without killing them makes biological sense. But the new variant of HIV revealed in the new paper demonstrates that’s not always the case. Viruses can mutate in a multitude of ways.

“Some people say that SARS-CoV-2 will evolve to become milder, as though this can be taken for granted; it cannot,” Chris Wymant, a researcher at the Oxford University’s Big Data Institute and first author on the study tells Inverse.

Here’s the background — The HIV virus mutates incredibly rapidly. In fact, Wymant says, “every individual [with HIV] has a virus that is different from everyone else’s, and indeed their virus changes over time.”

Many of these mutations make no practical difference — something we’ve also seen in many of the SARS-CoV-2 variants. The different variants of HIV are like siblings, Wymant says: They have different DNA but are within the same family. HIV researchers tend to group the mutations at the highest (most general) level and they are often determined by geography.

“For example in Africa, subtypes A, C, and D are most common,” Wymant says. “In Europe and the U.S., subtype B is most common. These differences between regions were established when HIV first began spreading around the world in earnest in the mid-twentieth century and have changed little since.”

The HIV virus can have wildly different effects on people, Wymant says.

“Some [individuals] progress to AIDS within months while others do not progress after decades; some have viral loads thousands of times higher than others.”

These differences are in part due to how well a person’s immune system can fight the virus, but in some cases, the virus itself can also make the difference.

“Every individual [with HIV] has a virus that is different from everyone else’s, and indeed their virus changes over time.”

Why it matters — People infected with the new HIV variant would, on average, “be expected to progress from diagnosis to ‘advanced HIV’ in 9 months, if they do not start treatment and if diagnosed in their thirties [and] the progression is faster still if they are older,” Wymant explains.

“Advanced HIV is known to cause long-term health problems. This finding, therefore, serves as an important reminder of World Health Guidelines on testing and treatment: Testing should be regular for those at risk of acquiring the virus and treatment should be started immediately when someone is diagnosed.”

A more virulent HIV virus sounds terrifying, but both Wymant and Joel Wertheim, a researcher and professor at the University of California, San Diego, say there’s no reason to panic.

“This variant is more virulent than is typical for HIV, but it’s not outside the observed range of virulence,” Wertheim says.

“Moreover, people in this cluster responded to antiretroviral treatment. So my expectation is that standard treatment options will be effective for this variant.”

“The public needn’t be worried,” Wymant concurs.

“Finding this variant emphasizes the importance of guidance that was already in place: That individuals at risk of acquiring HIV have access to regular testing to allow early diagnosis followed by immediate treatment,” he says.

“This limits the amount of time HIV can damage an individual’s immune system and jeopardize their health. It also ensures that HIV is suppressed as quickly as possible, which prevents transmission to other individuals... These principles apply equally to the VB variant.”

In a companion piece to the study, also published in Science, Wertheim takes the reader back to 2005, when a variant dubbed “Super AIDS” made headlines.

“Let us not forget the overreaction of the claim Super AIDS in 2005, when alarm was raised over a rapidly progressing, multidrug-resistant HIV infection found in New York that was ultimately restricted to a single individual,” he writes.

In contrast, the new HIV variant may “tell us something we don’t know that applies to HIV generally and not just this variant,” Wymant says.

How they did it — In much the same way virologists track Covid-19 variants, Wymant and his colleagues identified a large number of mutations in the subtype B group of viruses correlated with a substantially higher viral load.

They made the discovery by studying data using a “principal components analysis,” a computer modeling technique that can highlight correlations in data.

They found one variant with all possible mutations correlated with increased viral load. Of the 17 people they found with the variant, 15 were from the Netherlands.

The researchers then went looking for the variant in other populations. After coordinating with colleagues at Stichting HIV Monitoring, the researchers found another 92 individuals with the variant.

“We found they had a substantially higher viral load than individuals with other HIV viruses and we also found that their CD4 cells declined twice as fast,” Wymant says.

CD4 cells are your body’s T cells, specialized white blood cells that serve as a call to action for your immune system when an invader arrives.

“HIV attacks CD4 cells, gradually impairing an individual’s immune system, and the rate of this decline measures how much damage the virus is causing,” Wymant says.

The researchers called the variant the VB variant because it is both more virulent and part of the subgroup B viruses.

What’s next — The discovery tells us something fundamental about viral evolution and epidemiology.

“Viruses do not always evolve to produce benign infections. When virulence leads to increased transmission, natural selection will favor more virulent viruses,” Wertheim says.

“We saw this pattern with the Delta variant, and we see it in HIV. Moreover, HIV has been circulating in humans for more than a century, and yet it is still evolving. We should never underestimate the potential for viral evolution.”

While many have a casual attitude toward Omicron — arguing that because it’s more transmissible and less severe, we should just accept that everyone is going to get it and move on — that’s a dangerous perspective.

“We know that prevention is better than cure even just thinking short term: If I take actions to avoid getting an infectious disease, to prevent passing it on once I've got it, I've improved the health of people who otherwise would have become ill,” Wymant says.

“Prevention is also better than cure when we think about evolutionary epidemiology: Each infection that we prevent denies the pathogen an opportunity to evolve into something worse.”

The more we take a let-it-rip attitude toward SARS-CoV-2, the more we increase the chances that a more transmissible and virulent variant will emerge. While strict lockdowns may no longer make sense, basic mitigation measures like using N95 masks in indoor, public spaces make us all safer in the short term and the long term.

This article was originally published on