How music makes you feel may depend less on your brain than scientists once thought — study

Western concepts of how music should make you feel can obscure fundamental truths about human perception.

Need a challenge? Take your favorite happy song and type the title into YouTube, followed by “in a minor key.”

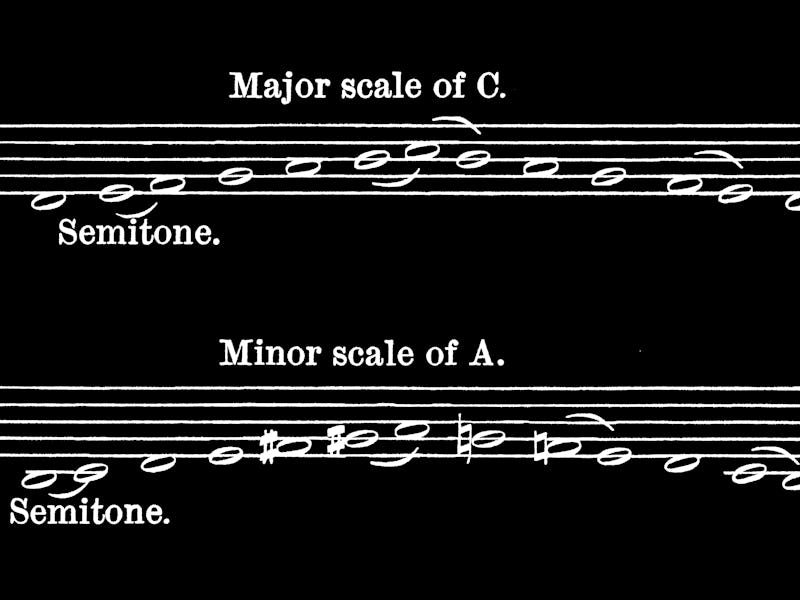

You’ve likely had this distinction drilled into your head by popular music and movies: The major key is “happy” and the minor key is “sad.” Major and minor keys form the basis of most Western music. These collections of notes are the building blocks of melodies and harmonies, and the key you compose music in can have a massive effect on the listener’s mood. These reactions can, in turn, beg a question: If a song makes one person feel so strongly, do all listeners feel the same way?

This idea of universality in music is in part owed to theories of universal human experiences, like Noam Chomsky’s theories of a fundamental grammar shared by all humans across cultures. But now, new research conducted in a remote area of Papua New Guinea supports the opposite idea — that our response to music is not innate but instead a learned response.

In Papua New Guinea, scientists discover evidence contradicting the theory that major key music is always perceived as happy.

Consider your chosen upbeat tune: With luck, someone will have created a minor-key version that doesn’t sound very happy at all. Most of these melancholy covers feel vaguely threatening — ideal for a dystopian sci-fi or a horror movie soundtrack. (My favorite so far is this depressing version of “Don’t Worry Be Happy,” by Bobby McFerrin.)

Some musicologists have theorized that a person anywhere in the world could hear your song’s two versions and recognize one as happy and the other as sad. The idea, so the theory goes, is that the underlying properties of major and minor note groupings prompt the human brain to certain reactions in predictable ways, but evidence for this theory has been mixed.

What’s new — In a study published on Wednesday, 29 June in PLOS One , researchers worked with 170 participants from seven villages in the remote Uruwa River Valley of Papua New Guinea. The research team presented the participants with pre-recorded melodies and harmonies in both major and minor keys and asked them to report which recordings they most associated with the feeling of happiness.

The remoteness of some areas of Papua New Guinea mean researchers can work with local populations to understand how cultural context influences musical perception.

Because of Papua New Guinea’s colonial history and missionary activity in the region, some of the people in the Uruwa River Valley identify as Christian and sing hymns based on Western music in church. In the study, church-goers did associate music in a major key with happiness, though not to the same extent as a control group of Australian participants.

Non-church goers in the Uruwa Valley, on the other hand, did not associate music in a major key with happiness, suggesting that the major = happy emotional response is learned from exposure to Western music and the cultural ideas it is suffused in.

“This study provides some really valuable data to a debate with a long history,” says Courtney Hilton, who studies music and psychology at Harvard University and was not involved in the new research.

Francis Be, head of the music department at the University of Papua New Guinea, was not surprised by the results. Traditional music from the country usually involves melodies sung by one person, or multiple people in unison, without the use of harmony. It makes sense that those less exposed to Western music through church services would have less of an emotional response to major and minor chords, Be says.

The Uruwa River Valley village where the researchers conducted the study.

Cross-cultural studies like this one are still rare since data from participants with minimal exposure to Western music is challenging to gather, says Imre Lahdelma, who studies the cultural perception of music at Durham University in the U.K. and was not involved in the recent study.

Designing musical prompts and questions that could be used to test both Papua New Guinean and Australian participants was a big challenge for the researchers. The team consulted local research assistants, community leaders, and language experts to attempt to make the questions as culturally relevant as possible, but it is difficult to ensure that the task is being interpreted the same way by both the participants and the researchers.

Digging into the details — The steep mountainsides of the Uruwa River Valley are blanketed by lush forests and misty clouds. The researchers stayed in the village of Towet, a three-hour hike from the small landing strip where they were dropped off — though the locals could have made the trip in half the time, recall study authors Eline Smit of the University of Konstanz and Andrew Milne of Western Sydney University. Both study the psychology of music.

Even in such a remote area of the world, local musical traditions have been impacted by Western music. Beyond the Christian hymns, groups of guitarists sing and play in string bands, or stringben in Papua New Guinea’s official language, Tok Pisin. And just as Western involvement impacted the music of the region, the Western perspective of musicologists alters how it is studied and described.

“It has been proposed that this ‘Western-centric’ approach has biased the understanding of the mechanisms behind music perception and production,” says Lahdelma.

“Cross-cultural music research is often in danger of continuing the ethnocentric and arguably somewhat colonial bias of asking non-Western populations to rate Western music examples, but hardly ever balancing it out by asking how we in the West, in turn, perceive examples from the target populations' music cultures,” he says.

But this lingering idea that Western musical features are universal makes it important to study different cultures, Lahdelma continues.

“Research studies like the study at hand are precious and important in revealing which aspects of music perception are culturally mediated, and which are possibly universal.”

Why it matters — While these results emphasize the role of culture in shaping our emotional responses to music, they don’t prove that these responses are entirely created by culture, says Hilton.

The Uruwa River Valley.

The major and minor keys have different acoustic properties — features with technical-sounding names like harmonicity and spectral entropy. The human ear and brain could process sounds with these qualities in particular ways that predispose us toward similar associations across cultures.

These kinds of innate similarities have been found across cultures linking facial expressions to emotion, as well as the sounds of languages, the authors say. One famous language example is the bouba/kiki effect, where participants are shown a rounded shape and a spiky shape, then asked which is bouba and which is kiki.

Participants across the world will usually call the spiky one kiki and the rounded one bouba, regardless of their language of origin — a captivating but baffling similarity.

What’s next — The authors also searched for other cultural commonalities during their time in Papua New Guinea. They are currently putting together their findings on a feature of harmony called auditory roughness.

Music sounds “rough” when two notes are too close together in pitch, causing them to clash in our minds, sounding grating and unstable. The researchers are investigating whether this association of roughness with instability could be consistent across cultures.

Searching for common ground in our perception of music encourages us to question the often-invisible ways that culture shapes how we see the world.

“We are stuck inside our own heads, so it's easy to assume that our own way of perceiving and experiencing music is like everyone else's,” says Hilton.

“Studying music cross-culturally helps us appreciate both what is shared across cultures as well as what makes each special.”

This article was originally published on