What you need to know about the surge of monkeypox cases in the US

The United States now has the most monkeypox cases outside of countries where it’s endemic.

On Saturday, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the monkeypox virus a Public Health Emergency of International Concern; the seventh time it has used its highest-alarm designation since its creation in 2005. The Biden administration is reportedly considering declaring monkeypox a public health emergency, according to the Washington Post.

While endemic in many countries in Central and West Africa, cases of monkeypox aren’t often found in high numbers outside those areas. When they are, cases are usually traced back to one of those locales. However, the outbreaks health officials have been monitoring since May of this year haven’t followed a similar pattern and case rates appear to be soaring. When Inverse first reported on Monkeypox in June, there were 33 confirmed cases of Monkeypox in the United States. As of Wednesday, the CDC data shows the number has now jumped to 4,639.

That’s a startling spike. In fact, the United States now has the highest number of cases outside countries where monkeypox is endemic.

“If things continue at this rate, it’s not hard to see how we might have a monkeypox crisis in this country come Labor Day,” Donald Alcendor, Adjunct Associate Professor of Pathology, Microbiology, and Immunology at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, tells Inverse.

How is monkeypox transmitted?

At first glance, it might seem like the jump in cases is evidence of a highly transmissible virus like we’ve seen with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19. Fortunately, that doesn’t seem to be the case.

Covid is primarily transmitted through aerosols, small droplets that can remain suspended in the air, or larger droplets inhaled via close contact with someone who has been infected. Contrary to all the grocery and mail sanitizing we did early in the pandemic, SARS-CoV-2 isn’t transmitted through fomites: touching the same object as an infectious person.

Monkeypox works almost the opposite way as Covid does, Scott Roberts, an infectious disease specialist and Assistant Professor at Yale School of Medicine tells Inverse. The virus spreads primarily through touch: When someone comes into contact with an infected skin lesion of someone else. That lesion harbors the virus, which is then transmitted to the person who came into contact with it. If that happens with a “weeping” lesion — one that is producing fluid — transmission can occur relatively quickly.

In this Centers for Disease Control and Prevention handout graphic, symptoms of the monkeypox virus are shown on a patient’s hand.

“A secondary mode of transmission would be droplet spread, so some kind of prolonged contact with an infected individual,” Roberts says. “If we think about Covid as a six-foot 15-minute rule, monkeypox is more a six-foot, three-hour rule. So it really requires close, prolonged sustained contact.”

The CDC notes that the virus can also be spread through “touching items (such as clothing or linens) that previously touched the infectious rash or body fluids,” and that “pregnant people can spread the virus to their fetus through the placenta.”

Infected animals can spread the virus to people through bites, scratches, or consuming meat from an infected animal.

Is monkeypox becoming more infectious?

The jump in cases is likely not the result of a more transmissible variant of monkeypox but instead an indication that the virus has been spreading in communities well before public health officials started identifying the outbreaks, testing, and contact tracing.

Alcendor notes that, unlike SARS-CoV-2, monkeypox is a DNA virus, which “is less likely than an RNA virus to have a high mutation rate.” So while a new, more transmissible variant isn’t out of the realm of possibility, it’s much less likely than it would be with a virus like the one that causes Covid-19.

There has been some confusion about whether or not the monkeypox virus, like Covid-19, can be transmitted through aerosols, in part because of confusing CDC guidance about masks and an old, viral study that made the rounds on social media in June.

“There was one study a number of years ago that showed it could have the potential to be aerosolized in a lab setting. Really what they do is they artificially make it aerosolized, and then just check, does it survive in the air, and they found that it does,” Roberts says.

But a lab experiment in which the virus has been aerosolized and is monitored in a chamber is very different than a real-world scenario. “My strong suspicion is that aerosols are a very unlikely or minimally impactful mode of transmission,” he adds.

How to avoid contracting monkeypox

The current outbreaks have largely been found in men who have sex with men. Monkeypox isn’t currently thought to be sexually transmitted, Roberts says, however, the lesions have in many cases been contained to areas around the genitals and mouth, suggesting that the skin-to-skin contact inherent in sexual encounters is responsible for transmission.

To prevent contracting monkeypox, the CDC advises avoiding the following:

- Close, skin-to-skin contact with people who have a rash that looks like monkeypox.

- Sharing utensils or cups with a person with monkeypox.

- Handling or touching the bedding, towels, or clothing of a person with monkeypox.

- “In Central and West Africa, avoid contact with animals that can spread monkeypox virus, usually rodents and primates. Also, avoid sick or dead animals, as well as bedding or other materials they have touched.”

Washing your hands often with soap and water or using an alcohol-based hand sanitizer can also help prevent monkeypox transmission.

What are the symptoms of monkeypox?

The most notable symptoms of monkeypox are lesions, which often look like a rash or blisters. Typically, those lesions are preceded by a few days of flu-like symptoms such as fever, swollen lymph nodes, headache, and muscle aches.

Because the smallpox virus is closely related to monkeypox, the smallpox vaccine can be used to prevent and treat the virus — if we have enough of it.

Alcendor notes that the 2022 outbreaks appear to be traced back to the West African clade (or type) of the virus. That’s good news, as the West African clade is associated with less severe symptoms and outcomes than the Central African clade.

However, with less severe symptoms, it can be harder to recognize that you’ve contracted the virus. Not only are some people not experiencing those flu-like symptoms before lesions appear, but the lesions are also less severe.

“That means some people will clinically present with a single lesion around the mouth or multiple small lesions around the genitals. And if you go and look for monkeypox images on Google, they send you something that’s much more hardcore,” Alcendor says.

Thus, it’s important to get any strange rash or lesion checked out by a doctor, especially if you’ve recently been in close contact with someone who contracted monkeypox.

According to the CDC, illness from monkeypox lasts between two and four weeks.

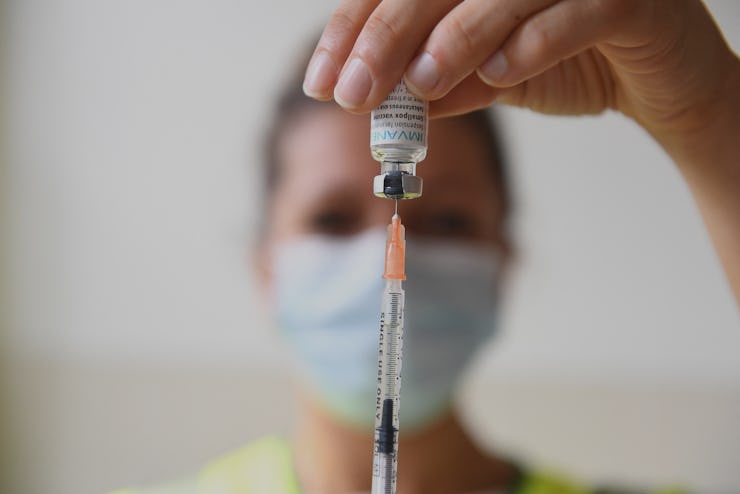

Are there effective treatments or vaccines for monkeypox?

There are no antivirals specifically for monkeypox, nor a monkeypox-specific vaccine. However, because the virus is so closely related to smallpox, smallpox vaccines and antiviral drugs can be used to prevent and treat monkeypox.

Currently, Roberts explains, health departments that are using smallpox vaccines to treat or prevent monkeypox are getting them from the Strategic National Stockpile — the country’s repository of medical supplies — so it’s not necessarily widely available in every state.

“In Connecticut, we cannot get the vaccine; it has to be approved by the Department of Public Health for those who are exposed to known positive cases because there have only been 22 cases here,” he says. “ New York City is the opposite — they’ve now expanded their vaccine access to those who are at high risk, such as men who have sex with men.”

If cases continue to balloon, Roberts expects we’ll see more states go in that direction — if manufacturers can increase the supply.

Who is most at risk for a severe case of monkeypox?

Historically, experts say, children experience the worst outcomes from monkeypox.

Because the 2022 cases outside endemic countries have largely been found in adults, Roberts says we need more data before determining how bad the outcomes outbreaks in kids could be.

“There are a few studies of children with monkeypox, but they're all in somewhat more resource-poor settings like West Africa. As far as I know, the two children in the United States who contracted it are doing OK,” he says. “But I think it makes sense until we have data to suggest otherwise to treat children as a vulnerable group that we should be more concerned about.”

Alcendor definitely has concerns. “Children are set to go back to school soon, some charter schools already have,” he says. “We know children are big huggers and kissers and horseplay and all that. And they don’t always have the best hygiene. So the idea of an outbreak in schools is very worrying to me.”

While unusual outbreaks of a virus are always a cause for concern, panicking is never the answer. Be vigilant about hygiene and get any unusual skin abnormalities checked out as soon as possible, especially if you’ve been in contact with someone who tested positive for the virus.

Both monkeypox and Covid-19 should serve as reminders that global health is public health: pathogens never stay in one country or even on one continent. Investigating and mitigating dangerous pathogens in any country make everyone healthier in the long run.

This article was originally published on