Differences in men and women's brains may reveal better ways to treat depression

A study of severe depression revealed a critical difference between men and women.

Women are two times more likely to suffer from major depressive disorder than men, but until recently, most preclinical studies into the underlying biology of depression only included men.

A new study tries to close the gap: In the new paper, scientists uncover biological mechanisms that can, in part, explain the gender differences in depression — and may even pinpoint a new potential biological signature of depression in women. The research could help improve diagnosis and treatments for both men and women.

In the journal Nature Communications, researchers from Laval University in Quebec, Canada demonstrate how prolonged stress changes mood-related brain regions in female mice — these changes are mirrored in postmortem brain samples taken from women diagnosed with major depressive disorder.

Earlier research done by the same study team found chronic social stress damages the blood-brain barrier in male mice and prompts depression-like behaviors. To the scientists, this suggested a direct link between how vulnerable one is to stress and neurovascular health. The blood-brain barrier plays two main roles:

- It is a physical fence which protects the brain and keeps toxins, pathogens, and harmful inflammatory molecules in the bloodstream out of the brain

- It allows water, nutrients, and vitamins to cross into the brain and feed neurons

“We hypothesize that blood-brain barrier dysfunction in depression could disrupt the brain’s homeostasis, allowing harmful molecules to reach it, altering neuronal function and behavior, particularly in regions involved in emotion and mood regulation,” explains first author and Ph.D. candidate Laurence Dion-Albert and lead author and assistant professor Caroline Menard.

How does depression differ in men and women?

When they tested their theories in mice and women, they noticed something striking: In male mice, the changes observed were linked to the loss of a protein called claudin-5 and this loss could be seen in a part of the brain called the nucleus accumbens, an integral part of the reward and emotional systems. But when the team repeated the experiment in female mice and the brains of women who had depression at the time of their death, they found the brain barrier changes caused by claudin-5 were in the prefrontal cortex — a different part of the brain. This part of the brain is associated with “anxiety, sadness, and self-esteem,” say Dion-Albert and Menard.

These experiments also reveal what may be a vascular biomarker of chronic stress — an inflammatory molecule called soluble E-selectin. This was found in high concentrations in the blood of the female mice and in the blood samples of women with depression. It was not found in the blood samples of men with depression.

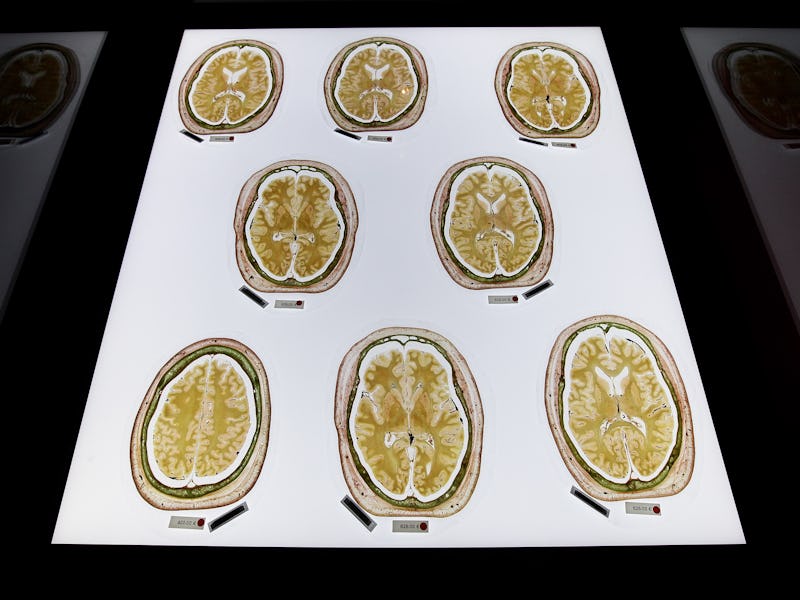

The prefrontal cortex is highlighted in green.

Discovering a depression biomarker is a game-changer in mental health research because scientists are racing to develop better treatments for depression. Current antidepressant treatments affect neurons and neurotransmitter ability, explains Dion-Albert and Menard. But 30 to 50 percent of patients respond poorly to these drugs, “suggesting the involvement of other biological systems in the pathology of depression, including blood-brain barrier breakdown,” they say.

They hope their findings “highlight the importance of investigating non-neuron centered mechanisms” and lead to a generation of more effective therapeutics for treatment-resistant depression.

But first, the potential of soluble E-selectin as a biomarker in women has to be confirmed in larger studies in people. Currently, the team is collaborating with research groups around the world to assess its validity in blood samples belonging to people with depression.

“We are also investigating how preventative strategies, such as physical exercise, can positively contribute to vascular health and prevent blood-brain barrier breakdown despite stress exposure, in a sex-specific manner,” Dion-Albert and Menard say.

While scientists work toward better treatments for depression, these findings move us toward a better understanding of why severe depression affects men and women differently. It’s a complicated, under-researched subject — the study authors note its imperative to have more mental health studies that examine female subjects. It’s known that depression disproportionately affects women: Now we can see how it manifests differently in the brain.

There’s room to grow in our understanding as to why this depression is more prevalent in women overall — and how much of that is to do with environmental influences and fundamental genetic differences. For now, scientists think the complex answer likely links back to hereditary, epigenetic, environmental, and endocrine risk factors. It’s possible, the authors of this study write, that sex and region-specific vulnerability of the blood-brain barrier can be explained by the presence of estrogen receptors — but we need more research to know for certain.