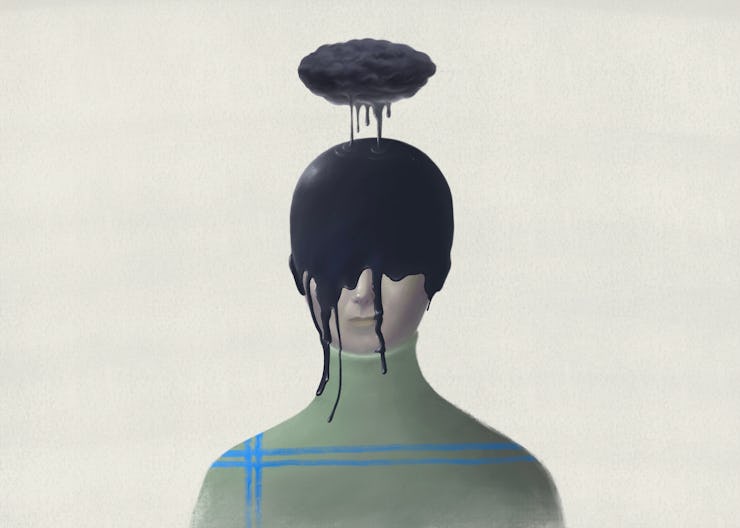

The brains of lonely people reveal why you can feel alone in a crowded room

A newly identified pattern of brain activity could explain why lonely people feel so isolated.

There are more people in the world than ever, but plenty of people still feel very much alone. According to a May 2020 survey, about three in 10 Millennials feel always or often lonely. These results mirror the findings of the same survey given in July 2019.

For those feeling particularly isolated — even before social distancing was a disease-prevention policy — scientists may not be able to offer a salve. But they can offer an explanation of why there’s a seemingly a chasm between yourself and the rest of the world.

Loneliness is a social feeling, but there’s an explanation for it in our brains. It begins in the medial prefrontal cortex, an area of the brain deeply involved in social cognition. According to research published Monday in the journal JNeurosci, it also alters how the brain represents "social maps" — patterns of brain activity that represent relationships.

The study evaluated 43 college students. The people who were closest to the students – like close friends or family – tended to elicit more powerful signals in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). Those signals were also strikingly similar to the patterns of activity shown when people think about themselves. The more distant someone is within the social network – say someone is just an acquaintance – the more different that neural pattern became.

However, for people who tended to have high levels of loneliness, the scientists found that this pattern looks strikingly different. People identified as lonely had lower levels of activation in the mPFC when confronted with cues about any other person, including those close to them. They also tended to have lower levels of overlap between patterns of brain activity linked to their own identities and those triggered by those around them.

Andrea Leigh Courtney is the study’s corresponding author and a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University. She tells Inverse that this pattern of brain activity could explain why lonely people feel so isolated from those around them. This phenomenon is also known as a “self-other gap.”

“We now have some evidence to suggest that this self–other gap might lie in patterns of brain activation associated with thinking about the self and others,” Courtney says.

Brain imaging revealed a single cluster within the medial prefrontal cortex where activity increased depending on how close someone was to the study participant.

The brains of lonely people – To determine the relationship between social relationships in the brain and loneliness, the scientists asked people to make character judgments about people they felt close to, acquaintances, and celebrities (including, but not limited to, Kim Kardashian and Mark Zuckerberg).

These three groups of people represented three levels of a social circle: inner circle, acquaintances, and people we’re familiar with but don’t know.

They also had people rate their levels of loneliness, which depended on how much they empathized with statements like: “I feel disconnected from others” or “my interests and ideas are not shared with those around me.”

Brain scans revealed just how differently the brains of participants who felt the most lonely processed these social circles. Megan Meyer, a study co-author and assistant professor at Dartmouth College, tells Inverse that you can think of those differences in brain activity like constellations.

The way your brain activates when you think about yourself is one constellation, and the way your brain lights up when you think of others is another constellation. In non-lonely people, there’s a lot of overlap between your constellation, and that of a close friend. There’s less overlap between yours and that of an acquaintance, but it’s still there.

“For lonelier individuals, their constellation for thinking about oneself is very separated from their constellation for thinking about others,” says Meyer. "Their constellation for thinking about others is pretty overlapping."

The patterns of brain activity elicited by close friends and acquaintances are more closely related to one another than they are to the one that’s activated when you think about yourself, Meyer explains.

The similarity of medial prefrontal cortex activity was the most similar for close others compared to acquaintances and celebrities. For lonely people though, these patterns were even more disparate.

All the lonely people – Loneliness does seem to follow clear patterns. A 2012 study that examined levels of loneliness in 2,393 UK citizens between 15 and 97 years old found that that people above the age of 65 and below the age of 25 tend to demonstrate the highest levels of loneliness. These study authors suggested that loneliness follows a u-shaped curve, which means that it peaks early in life, and then once again late in life.

Other studies have also found that loneliness follows this u-shaped curve, but argue higher levels of loneliness tend to be linked with demographic and socioeconomic categories, like being a woman, having low socioeconomic status, and living in a nursing home.

Ultimately, the authors of this new study say that the best way to understand loneliness is by understanding how it affects the brain. Loneliness is not necessarily a consequence of your living situation, they explain — it's a state of mind.

“We've known for a while that loneliness is a condition of subjective social disconnection, so we hoped to identify a brain mechanism that might explain this perceived self–other gap,” Courtney says.

This new study shows that loneliness really does show up in brain scans, at least for 43 college students. Even if you’re around others, you can still feel lonely. In fact, loneliness likely has little to do with truly being alone, and more to do with the fact that you feel alone no matter what your circumstances are.

That chasm between yourself and others isn’t a fantasy — it might actually exist in your brain.

Abstract: Social connection is critical to well-being, yet how the brain reflects our attachment to other people remains largely unknown. We combined univariate and multivariate brain imaging analyses to assess whether and how the brain organizes representations of others based on how connected they are to our own identity. During an fMRI scan, female and male human participants (N=43) completed a self- and other-reflection task for 16 targets: the self, five close others, five acquaintances, and five celebrities. In addition, they reported their subjective closeness to each target and their own trait loneliness. We examined neural responses to the self and others in a brain region that has been associated with self-representation (medial prefrontal cortex; MPFC) and across the whole brain. The structure of self-other representation n the MPFC and across the social brain appeared to cluster targets into three social categories: the self, social network members (including close others and acquaintances), and celebrities. Moreover, both univariate activation in MPFC and multivariate self-other similarity in MPFC and across the social brain increased with subjective self-other closeness ratings. Critically, participants who were less socially connected (i.e. lonelier) showed altered self-other mapping in social brain regions. Most notably, in MPFC, loneliness was associated with reduced representational similarity between the self and others. The social brain apparently maintains information about broad social categories as well as closeness to the self. Moreover, these results point to the possibility that feelings of chronic social disconnection may be mirrored by a ‘lonelier’ neural self-representation.