Ketamine and the brain: Why a new discovery may lead to improved antidepressants

It can take several weeks for traditional antidepressants, like SSRIs, to show an effect.

While antidepressants can provide some relief, two major hurdles keep these drugs from helping everyone with major depressive disorder (MDD).

One is that some people experience what’s called treatment-resistant depression. Because approximately 30 percent of people with MDD fail to respond to antidepressants, scientists are working toward tweaking the application of serotonin uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and finding new, more effective therapeutics.

The other issue is it can take several weeks for traditional antidepressants, like SSRIs, to show an effect. This therapeutic delay is especially an issue for individuals at risk for suicide.

This is in part why researchers are so interested in the potential of ketamine. Both a legal anesthetic and popular party drug, a growing body of research suggests it also induces antidepressant effects. Most critically, ketamine is a “rapid” antidepressant.

“Clinically, ketamine acts within an hour or so after administration of a single dose, and in some patients, the effect lasts up to a week or more,” Ege Kavalali, a professor at Vanderbilt University, tells Inverse.

The discovery — Kavalali is a co-author of a recent study that examines exactly why ketamine induces this rapid effect. He explains that since their initial work on the synaptic mechanisms underlying this action, Kavalali and co-author Lisa Monteggia have “been trying to elucidate a common synaptic point of convergence targeted by all rapidly acting antidepressants.”

“Our goal is not only to understand the mechanisms underlying ketamine action as a rapid antidepressant but to develop synaptic assays to predict potential efficacy of novel rapidly acting antidepressants,” Kavalali says.

These packs of ketamine lozenges are given to patients at Field Trip, a psychedelic therapy clinic in Toronto, Canada.

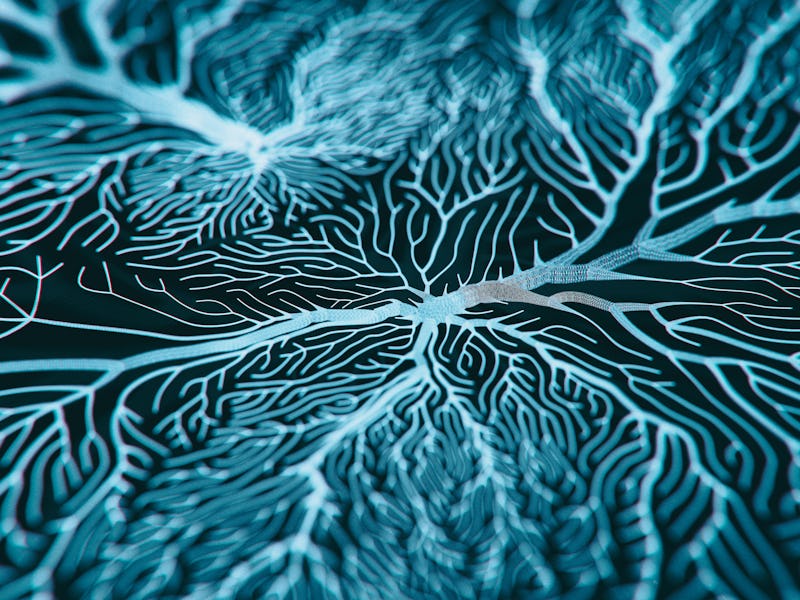

What allows neurons to communicate with each other are synapses — these are junctions between two neurons. Synaptic plasticity, in turn, reflects changes that happen at these synapses. (Long-term synaptic plasticity is needed for storing information in the brain, like memories.)

In the journal Cell Reports, Kavalali and the study team report that the rapid antidepressant action associated with ketamine is because of specific synaptic effects.

This result is the path forward Kavalali and Monteggia were looking for: The hope is that if new therapeutics are developed to target this same pathway, then they could also provide rapid relief.

What comes next for ketamine — This study was preclinical, meaning it looked at hippocampal neuronal cultures in a lab. For ketamine to rapidly work, a protein called eEF2K becomes inhibited. This inhibition is what leads to those synaptic effects, described in the study as “two independent signaling pathways” converging “at a common synaptic endpoint.” It’s this “synaptic homeostatic plasticity” that causes the effect the scientists were looking for.

But while the study links this synaptic effect, technically called “homeostatic synaptic up-scaling,” to a change in behavior, exactly why is still unclear. That’s what the study team wants to continue to examine, as well as ask how these synaptic changes influence neuronal circuits.

The setup at the psychedelic therapy clinic Field Trip in Toronto, Canada. Patients sit in this environment while on their “ketamine trip.”

While this is explored, other scientists continue to probe ketamine’s power as a therapeutic. It’s nearing a tipping point that’s almost mainstream: In 2019, the FDA approved a nasal spray derived from ketamine, paired with an oral antidepressant, as a treatment for depression.

What’s likely to become a more common form of therapy, experts say, is pairing doses of ketamine with cognitive behavioral therapy. But getting the exact dose right is something scientists are still working on, and there are dozens of trials going on right now designed to probe its efficiency.

That’s not to say that, despite these gaps in information, people aren’t already using the drug as a treatment for depression. In the United States and the United Kingdom, private clinics are already offering ketamine as an “off-label” prescription — meaning it can be used to treat a condition outside of its original medicinal intent.