Male and female bodies can respond differently to intermittent fasting

Here's what we know so far.

If you’ve ever eaten dinner at 7 p.m. and then skipped breakfast, you’re an intermittent faster.

Intermittent fasting is a darling of the internet and an eating pattern that restricts the times you eat, not necessarily the foods. It’s compelling to men, women, and everyone in between for its simplicity — but preliminary research suggests its effect might be different depending on your sex.

It’s challenging to study diet interventions like intermittent fasting. For one, it’s expensive to track humans and what they eat for months. Plus, human participants, who might forget or alter reports of what they actually ate, are unreliable.

Even mouse studies, which are much easier to control, overwhelmingly favor studying male mice because of the presumed “variability” in female mice and misconceptions about the role of reproductive systems.

But a handful of studies do offer some preliminary ideas on variation by sex. While some data suggests men and women experience weight loss and body composition changes, other research suggests men and women undergo different changes when it comes to factors like glucose and fatty acid response.

What you need to know first — Very few studies have investigated which sex could benefit more from intermittent fasting, whether it’s eating little or nothing only every other day (alternate day fasting), or restricting eating to just a certain window in the day (time-restricted eating like 16:8). Those that are short-term studies, and show mixed outcomes.

Many people embark on intermittent fasting regimens (alone or combined with other dietary restrictions) to lose weight — or more specifically, to lose fat mass. Some studies have investigated this, but most examine other metabolic markers like blood glucose, insulin regulation, and triglycerides.

We still have very little information, however, on the long-term effects of various kinds of fasts, or differences that might exist for men and women who have obesity as opposed to those who don’t.

Men and women may respond differently to intermittent fasting, but there’s not enough research yet to know for sure.

Intermittent fasting: The similarities across sexes

Kristina Varady, a professor of nutrition at the University of Illinois, Chicago, studies intermittent fasting in relatively large human trials. Her research suggests men and women respond similarly to alternate-day fasting and time-restricted eating.

“Men and women have similar adherence rates, weight loss, and body composition changes with both diets,” Varady tells Inverse. “However, the data are very limited.”

One study Varady co-authored found no real differences between men and women who tried an “alternate day fasting” diet for 12 weeks. They ate 500 calories every other day and could eat what they wanted on the rest. “Bad” cholesterol decreased slightly more in premenopausal women versus post-menopausal women, but there were no significant differences in weight loss, fasting glucose, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides.

Another study she co-authored, which looked into what might predict success with a similar alternate day fasting diet, focused on factors like age, sex, race/ethnicity, and baseline body weight/BMI. It found that people between 50 and 59 years old and white males lost slightly more weight. Though 60 percent of all 121 participants lost 4 to 8 percent of their body weight, sex didn’t seem to make a difference.

Intermittent fasting: The differences between men and women

Other researchers have tackled the question from a different angle: they measured glucose response and “muscle gene expression” in men and women who did alternate day fasting. A glucose response is the body’s ability to break down glucose.

A 2005 study found that after three weeks, women had a slightly worse glucose response than men. The men in the study, however, had worse insulin response — a finding supported by a 2007 paper. There were no changes in muscle genes.

There’s also evidence suggesting that, after extended fasting, triglycerides accumulate in the livers of men — while in women, they accumulate in muscles. Triglycerides are the fatty acids that accumulate in the blood. This paper, published in 2012, also found “women and men had identical fasting responses in whole-body and hepatic glucose and oxidative metabolism.”

And in a 2006 study, men and women who fasted for 24 hours had slightly different experiences in their self-reported hunger: women reported feeling more hungry.

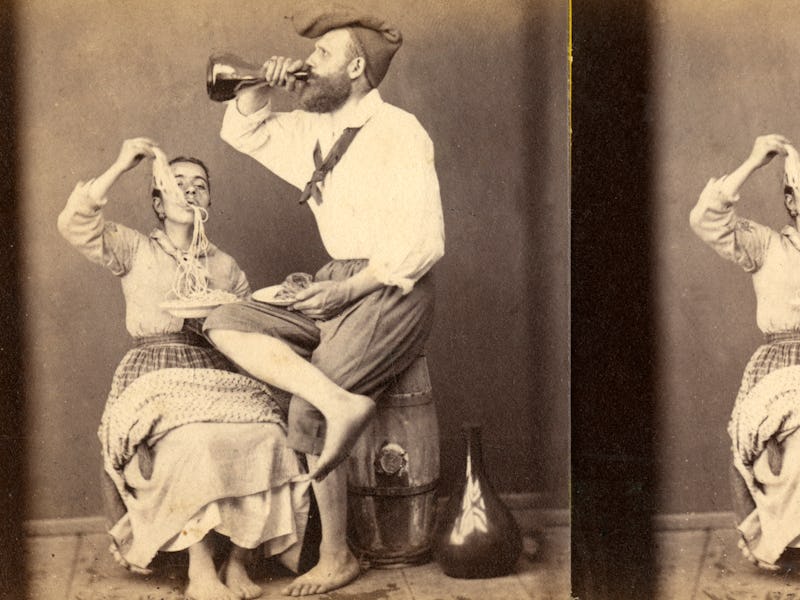

Intermittent fasting normally restricts nighttime eating — we’ve all been there, though.

The connection to keto

Fasting, the practice of not eating or eating very little, is often compared to a ketogenic diet, where one consumes very few carbohydrates.

This is because they appear to produce one similar effect: the body switches its energy source from blood sugar (glucose) to the ketones the body generates from fatty acids. What we know about sex differences in response to ketogenic diets and low-carbohydrate diets might hint at how men and women respond to intermittent fasting.

One particularly expansive 2020 study published in Nature looked at the differences between 609 “healthy” men and women on either low-carbohydrate diets and low-fat diets for an entire year. The men on a low-carb diet lost more fat mass than the men on low-fat diets — but not women. Men also had an easier time actually adhering to their diets. Ultimately, men on low-carb diets lost significantly more weight, lean mass, and fat mass than women on low-carb diets.

A number of animal model studies have found that alternate-day fasting had adverse effects on female mice: In one, female mice on a calorie-restricted, intermittent fasting diet responded much more dramatically than male mice on the same diet. Female mice had “heightened cognition and motor activity, combined with reproductive shutdown,” which the authors speculated “may maximize the probability of their survival during periods of energy scarcity and may be an evolutionary basis for the vulnerability of women to anorexia nervosa.”

The Inverse analysis — Intermittent fasting it’s too new in the grand scheme of nutrition research for there to be a scientific consensus on its long-term safety, let alone a definitive answer on how it could work differently by sex.

As with any diet, eating practice, or eating pattern, it’s always best to consult with a trusted healthcare professional before making changes to what you eat. Although intermittent fasting is used for a number of reasons, weight loss, in particular, should be approached with caution and sensitivity. What’s more, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics does not recommend intermittent fasting. And it’s listed (you guessed it) in their “fad diets” category.

This article was originally published on