Doctors fighting Covid-19 tell Inverse they feel “hung out to dry”

"I know it's going to get worse."

The hospitals where Derek Farley works are not overrun with Covid-19 patients. Yet.

But he is preparing for the days ahead.

Farley, a doctor of osteopathic medicine, believes it is only a matter of time before he will have to trade in medical-grade protective masks for a snorkel that looks like a prop for the '80s TV show MacGyver.

Farley works in two free-standing emergency rooms and two surgical hospitals as an independent contractor. He's based in Little Elm, Texas, a town situated between Fisco and Denton in the northern reaches of the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex.

On Friday, he treated his first Covid-19 patient. His experience is far from treating the exponential growth of patients in cities like New York City, but he anticipates a surge soon.

"We're starting to see it, even in small-town Texas," he says. "I know it's going to get worse."

The stark truth is there are not enough supplies to weather the coming storm, he says.

Already, his hospital has started to ration N95 masks, which help protect doctors from droplets that spread coronavirus. At one hospital where he works, there are only two sets of goggles that can prevent the virus from contacting mucus membranes in the eyes. So Farley went into his garage, embracing his inner Richard Dean Anderson.

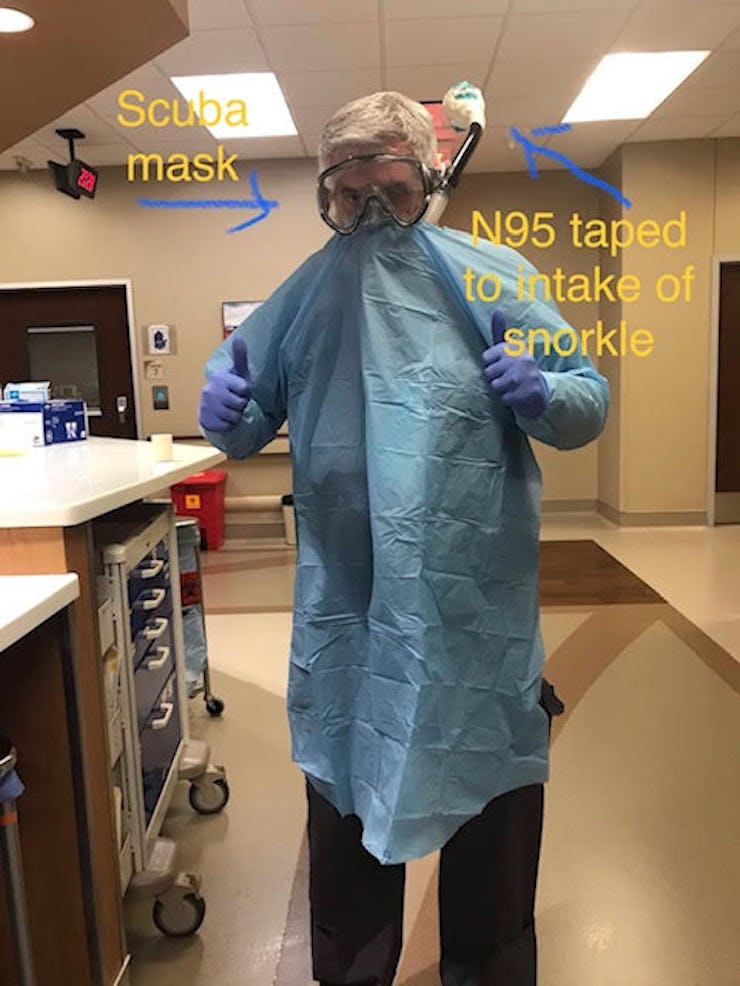

He pulled out a snorkel and mask, and then attached an N95 respirator to the snorkel's spout.

It wasn't perfect, but when he put it on his Facebook feed, he started to get emails from all over the country, asking him how he did it.

"It really feels like we've been hung out to dry."

Despite efforts to flatten the curve and avoid the overwhelm of healthcare systems, medical supplies have been pushed to the limit, which spurred interest in Farley's DIY medical invention.

In a widely circulated New York Times video taken from inside a hospital in Queens, New York, an ER doctor describes that despite official assurances from government officials, the reality inside hospitals is far different. Key tools like ventilators and personal protective equipment (PPE) have dangerously dwindled.

That sentiment is in line with statements from leading medical groups like the American Hospital Association, the American Nurses Association, and the American Medical Association.

In a co-written letter addressed to President Donald Trump, the leaders of those groups write:

"Even with the infusion of supplies from the strategic stockpile and other federal resources, there will not be enough medical supplies, including ventilators, to respond to the projected COVID-19 outbreak."

New York, but everywhere — In places that have yet to experience a caseload like that in NYC, Farley says his ingenuity isn't a cure for the problems facing his hospital, despite the considerable feel-good factor.

Instead, it is a symptom of a far more dangerous disease: Doctors simply need more resources to fight the coronavirus, partially because of hoarding of equipment, but also because of inadequate actions from regulators, Farley says.

Farley and his snorkel mask contraption which is a makeshift measure to protect against exposure to coronavirus droplets.

"The policymakers didn't foresee this or put any readily actionable plan that would help us out. You're asking us to intubate these folks and expose ourselves without the proper equipment. It really feels like we've been hung out to dry," Farley says.

Equipment like N95 respirator masks, a PAPR (a hooded system), or other eye protection are the items in shortest supply.

"If you don't have good facial protection, your likelihood of inhaling aerosolized droplets that are full of virus goes way way up," he says.

A recent survey of more than 8,200 nurses from all 50 states produced by National Nurses United (a nurses' union) found that only 55 percent of nurses had access to N95 masks. Only 27 percent had access to PAPRs, and only 24 could confirm that their employer had the tools on hand to survive a patient surge (worryingly, 38 percent of nurses didn't know the answer to that question).

A spokesperson for Vizient, a healthcare services company that specializes in medical-supply chains tells Inverse that hospitals have increased their purchase rates for medical supplies in response.

Vizient serves more than half of the nation’s healthcare organizations.

"We’ve heard reports that some Vizient hospital members are purchasing 10x their normal demand of critical PPE supplies," says Cathy Denning, who works at Vizient. There is also a critical need with some hospitals for additional ventilators.

"I don't think we're confident that the supply chain is actually working."

Some hospitals that have yet to see a surge in patients are preemptively rationing. In Philadelphia, Megan Lane-Fall is an intensive care doctor who tells Inverse her hospital is trying to avoid a New York-like situation.

"We’re not in surge, we don’t look like New York or Louisiana or Georgia or Florida. We’re not there yet, but we’re trying to conserve so we don’t get there," she says.

One of the major issues hospitals are facing is that the supply chain appears to be disrupted. When doctors ask for masks, they tend to get them, she says. But when they ask for PAPRs, she is never sure what is going to arrive in each shipment.

"There are interruptions in what is actually getting delivered to us. We know that this isn’t unique to us," says Lane-Fall, who is also a professor of Anesthesiology and Critical Care at the University of Pennsylvania.

Doctors fundamentally don't trust the supply chain, she says. That drives the need to come up with contingency plans, conservation strategies, or, makeshift devices like Farley's snorkel.

"I don't think we're confident that the supply chain is actually working, which makes us even more worried and needing to conserve the PPE that we have," she says.

What needs to change? Restoring faith in the supply chain begins with providing a "massive uptick in the production of medical equipment," Lane-Fall says. That includes PPE, as well as ventilators, and other key medical supplies.

3M, a major manufacturer for medical equipment, has already committed to doubling mask production. There are other options on the table, too.

"We need other companies that are not traditionally making this material to make it," Lane-Fall says.

Thankfully, this is starting to happen. Ford and GE Healthcare have committed to manufacturing PAPR devices alongside 3M. Tool manufacturer Harbor Freight committed to donating all masks, gloves, and face shields to hospitals. And Elon Musk has committed to donating "hundreds of ventilators to New York Hospitals," per a tweet from New York City's mayor, Bill de Blasio.

The Defense Production Act, which Trump invoked on Friday, gives the government power to turn privately owned factories into production centers for war supplies (medical supplies in this case). But the DPA isn't a panacea, say experts. It is far from a guarantee that that equipment will reach hospitals across the US, especially those in rural areas like where Farley works.

"The nightmare becomes if we get as busy as New York, and all of Fort Worth and Dallas have saturated their hospitals, and I've got somebody who needs to be on a ventilator for an extended period of time," he says. "Where am I going to send this person?"