A beginner's guide to weight lifting: How to get started and what to expect

The choice is easy and there’s no downside.

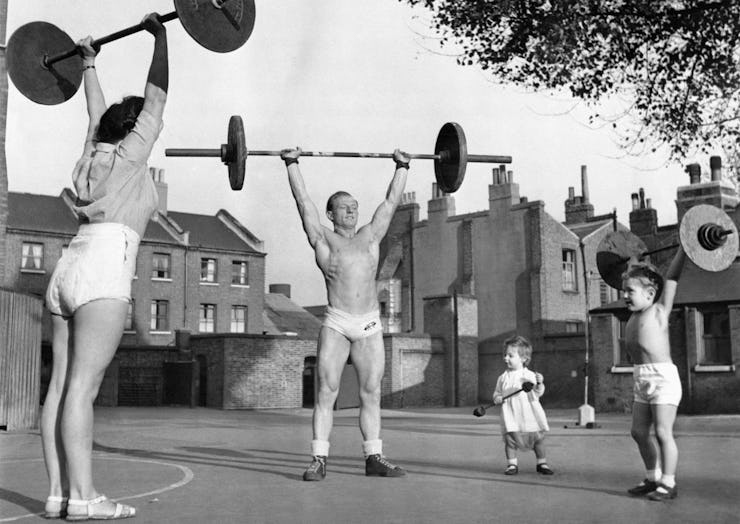

Even with gyms closing, New Year's Eve is coming and people want to get in shape. But starting the steps to take on a new exercise program can be confusing. It feels like there are one hundred ways to get fit, and just as many checklists, strength goals, and pieces of data to sift through before making a decision. Synthesizing everything can feel paralyzing. Which exercises should you do? And how? If you’re thinking about lifting, how do you know it’s for you?

The choice, really, is easy, and there’s no downside. Being active in any way is a good thing. Some exercises might be better than others at achieving certain goals, but all are good. Choosing between lifting, or yoga, or swimming, or running shouldn’t feel overwhelming. It’s like picking dessert at a restaurant! There are no downsides, the decision isn’t permanent, and going one way doesn’t preclude a change of direction down the line. In fact, related athletic experience often helps.

Running can be a mystery, but people choose to lift for different reasons. Some people like the feeling of lifting weights — the pump. Some people simply like hanging out at the gym. Not everyone enters a gym with goals, but many who start lifting for fun adopt them. For example, after a few months of curls, you might want to hit a milestone squat. To get there, you don’t have to start from scratch, but you do need a plan and expectations.

Step one: Bring in a program.

Most lifters reach these goals through programs, which are planned series of regular workouts that go on for months. There might be an infinite number of programs, and picking one gives pause. Some programs build up to a max weight attempt; some test strength, some build it, some test skill. But as far as new lifters are concerned, the similarities between programs outweigh their differences.

Lifters’ goals and what a program can actually deliver meet in the middle. Lifters generally want to get strong or big. Some may have more specific goals: like replicating an actor or actress’s look in a movie, or getting in shape for pick-up sports, or staving off back pain. Most programs can achieve these goals, but none are specifically designed for them.

Programs deliver on goals as a side-effect. Powerlifting programs, by training the sport’s three main lifts, are an excellent way to get strong and a good way to get big — but are designed for expertise in those lifts. Bodybuilding programs, where lifting is a means to the end of molding a body into the shape most ideal for winning a posing competition, will, as a side effect, strengthen a lifter as well.

Quick language note. This column has used the terms weightlifting, powerlifting, bodybuilding, and strength training interchangeably as short-hand for working out with weights, but they are different things. Powerlifting is a competitive sport where the total weight for three lifts is counted; its programs maximize their expression. Bodybuilding is a sport that emphasizes physique — parts of it over others — and its workouts reflect that. Weightlifting is what they do in the Olympics — there's a difference between weight lifting (two words) and weightlifting.

A good, proven program places a lifter on a continuum and builds strength and size, even if it prioritizes one over the other. This should be freeing for lifters. If you Google around and ask questions, you’ll find a program you need. Choice is good up to a point. But it’s like getting a tattoo. You don’t get the one in your head, but the one at the shop. The key is living up to a program that’s good enough for everybody else in the past. Only when lifters temper their expectations for a perfectly-tailored workout plan can they get to work.

But while strength training comprises hundreds of hyper-specific goals, its foundations — for starting a program, sticking with it, and progressing — are simple. And no matter the program, or goal, or lifter’s age, ability, or health level, there’s only one way to succeed. Lifters need to eat right and get lots of sleep and do as much as they can, but no more than that.

Step two: What to expect and what to ignore

But what about the program? Hang on — there’s still a bit of theory left. Because new lifters are more adaptable, they can put on muscle easily through almost any combination of exercises. Younger lifters will see the most adaptation, but new lifters more advanced in age should also progress, from middle-aged folks to seniors. Older lifters are more likely to have been injured and get injured, and so desk jockeys and senior citizens should get movement assessments before they get under the bar. But progress is real, no matter the age, so long as there’s adequate sleep, and nutrition, and effort.

Because new lifters are more adaptable, they can put on muscle easily through almost any combination of exercises.

The anecdotal evidence that every exercise, good or bad, seems to work for beginner lifters is backed up by science. A study published in the Journal of Applied Physiology suggests expenditure is the most important factor in a workout’s success, more than weight moved or a number of reps. Professor Stuart Philips, the study's senior author and a lifter himself, says “consistent practice combined with good nutrition and practicing good form and working to fatigue — no matter what the load — is what makes up the majority of results.” It’s one reason why people who do the wrong lifts the right way still seem to get big.

No matter the program — which I’ll get to soon — workouts should be performed to max. Max, in this case, does not need to mean a heavy weight, but the lifter’s subjective maximum, or close to it. The weight should feel, if not heavy all the time, like it’s there — and at the end of a workout, a lifter should feel spent.

A heavy weight, of course, is different from a harmful one. It’s important to distinguish between pain. Glutes and thighs screaming after a squat session is fine. Sharp pain in your back isn’t. Trainers I’ve spoken to say that sort of “bad pain” should never be felt higher than a two on the 1 to 10 scale. If it is, you should stop.

Step three: How to choose a program

For any program, form is important: movements, no matter the weight, should be fluid, smooth, and fast.

There are, however, exceptions, like testing a one-rep max, or high RPE lifts at the end of a program. Lifters should tape their workouts, and have a coach or peer review their form; supervised lifting seems ideal at the start. It’s no good if a squat is balky or a deadlift has no range of motion. That might mean the weight is too heavy, or that a lifter is too stiff or weak, to earnestly push themselves with barbell work. These types of situations should be run by a coach, and often mean more prep is needed. This means bringing in a powerlifting ramp-up program, or mobility work, or a dumbbell program. While these steps back are disheartening, they’re necessary. Barbell work is a means to an end but is also a skill. It requires proprioception — a sort of spatial awareness that sometimes needs to be developed.

Very roughly speaking, if lifters prioritize diet and sleep, they will get stronger and bigger working on any program. (Macros counting is the path to “solving” the food problem, and adequate nutrition can stave off soreness. Lifters should aim for at least seven hours of sleep a night.) Which takes the pressure off finding a perfect program.

Luckily, there’s a wealth of good ones to choose from. So-called beginner powerlifting programs — like Greyskull — are great and get results. More specialized programs, like GZCL are designed for a variety of lifters and work well for beginners. Strong Curves is designed for women (though there’s no need for women to pick a gendered program). There are dumbbell programs designed for people without access to barbells, are ideal for lifters in quarantine, or those who don’t want to pay for a gym. There are bodyweight programs, bodybuilding ones, programs for Olympic weightlifting, and ones for explosivity. It’s an endless list, and a welcoming one: any, if taken seriously, will deliver results.

Now that the theory is down, here’s an example of how a powerlifting timeline might work. A lifter in December wants to get strong, and picks a program, settling on Jim Wendler’s 5-3-1, which is somewhat out of vogue, but has worked in the past, and will work in the future, and has a variety of options beyond the beginner option.

After reading Wendler’s book a few times, and understanding Wendler’s schedule and goals, a lifter will find their one-rep max — Wendler says when in doubt, go too light — get a kitchen scale, and begin buying decent groceries. Come January, the program starts, and a lifter should follow the workouts, and do the conditioning, aiming for fluid, strong lifts, and a good range of movement. (If that’s too hard, lower the one-rep max, or start a GPP program, or a different beginner program that builds up proprioception, or talk to a coach.) Eat above maintenance, and sleep. It will work.

Any other program — powerlifting or bodybuilding; barbell or dumbbells, trendy or not — will shake out the same. The difference in results between the handfuls of fine, vetted programs is negligible compared to the slide that can happen if a lifter eats poorly or shirks an exercise. Choose almost any protocol off here, and if you work hard, you’ll see results. It’s as much about the effort, and the lifter, as the program.

What’s nice is that since lifters lift for years, from youth into old age, there’s no rush. Sometimes the new year isn’t the right time to start. If, when the calendar turns, you can only work out once a week, and do arms — do that. When it’s easy, do more. There’s no perfect program, or path, just habit and effort, and adjustment. If you want to start lifting in the new year, be prepared to lift beyond it. That long timeline is freeing. It’s through routine that all other things come.

Leg Day Observer is an exploratory look at fitness, the companion to GQ.com’s Snake America vintage column, and a home for all things Leg Day. Due to the complicated nature of the human body, these columns are meant to be taken as introductory prompts for further research and not as directives. Read past editions of Leg Day Observer for more thoughtful approaches to lifting and eating.

This article was originally published on