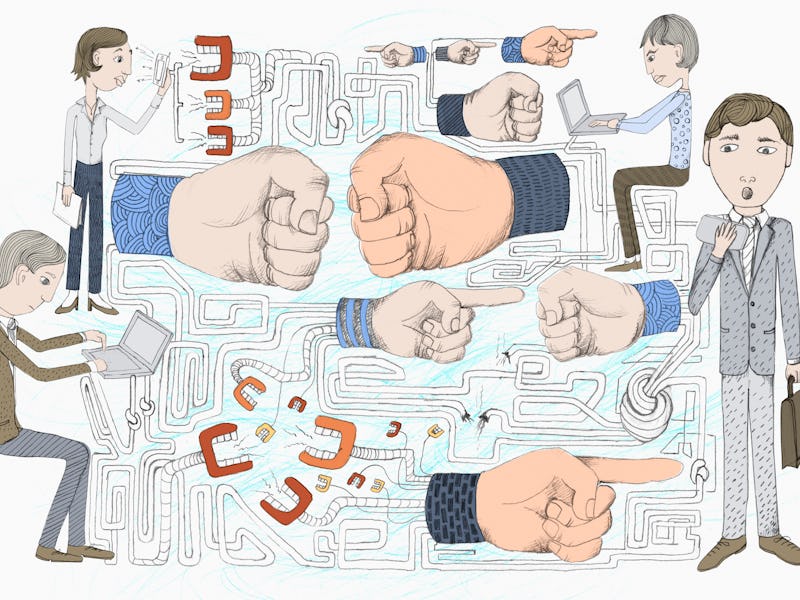

How to deal with a workplace bully

It’s hard to change a coworker's behavior, but there are strategies that can minimize the impact.

As much as people can try, it’s near impossible to check emotions at the office door. That can be fine. Leaders with high emotional intelligence — the ability to harness and effectively interpret emotions — tend to cultivate loyalty and productivity from colleagues.

But what happens when professional life gets a bit too personal — when a coworker snaps on a call or undermines you in a meeting?

It turns out, work conflict — or incivility, as researchers call it — can fuel a psychological phenomenon called rumination. These uncomfortable incidents turn on a painful replay setting in our brains that can last long after people leave the office.

According to a 2019 study published in the Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, workplace incivility also comes with some hidden health costs. In the study, experiencing rude or negative behavior at work, such as being judged or verbally abused, was linked with more symptoms of insomnia, including waking up multiple times during the night.

Study co-author Caitlin Demsky, an organizational psychologist at Oakland University, says this harmful cycle is hard to disrupt.

“Rumination signals an increased mental and emotional activation, which in turn can make it more difficult to 'switch off' and fall asleep easily,” Demsky tells Inverse.

Rumination, and the poor quality of sleep and insomnia it spurs, wear on the body over time. Bad sleep can contribute to obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. It also makes people worse at their jobs.

This week, Strategy explores how to keep work conflict from sending you into a tailspin that can ultimately harm your health. It’s hard to actually change a colleague's behavior, but it’s easy to use strategies that can retroactively minimize the impact of that behavior on you.

I’m Ali Pattillo and this is Strategy, a series packed with actionable tips to help you make the most out of your life, career, and finances.

Office drama— Workplace incivility refers to “behaviors that violate our expectations for civil behavior at work,” Demsky explains. Behaviors like gossiping, ignoring or excluding others, or discounting someone's opinion in an area in which they have relevant expertise all fall under this umbrella.

"Although workplace incivility may often be seen as low-level, ambiguous behavior — for example, who hasn't caught themselves engaging in workplace gossip at one point in their lives? — workplace incivility can have far-reaching effects that follow employees home after the work day is done," Demsky says.

Researchers estimate that between 55 and 98 percent of United States employees report experiencing workplace incivility in the office on a monthly basis. In 2011, researchers found half of employees reported being treated rudely at work at least once a week.

In an ideal world, workplace incivility should be prevented before it happens, not handled after the fact.

But given the extremely high prevalence rate of workplace incivility, it may be difficult to rid the workplace of 100 percent of incivility, Demsky says. More often than not, employees are left picking up the pieces.

“Because workplace incivility signals a violation of workplace norms, these behaviors can leave employees questioning their place within the organization and revisiting the experience after it's occurred,” Demsky says.

People repeatedly go over the interaction at work and when they're off the clock, trying to make sense of where things went wrong. That rumination can prompt sleeplessness, igniting an unhealthy cycle. Growing research suggests sleep quality is also linked to a number of important work outcomes, including higher levels of employee engagement, job satisfaction and task performance, and lower levels of turnover intentions and work-family conflict, Demsky says.

And when people don’t get enough sleep, they’re more likely to commit unethical behavior and abusive supervision.

Recovery + resilience— To stop work incivility from hijacking life in and outside the office, Demsky suggests three research-backed recovery experiences:

1. Psychological detachment from work: This means mentally and physically separating oneself from work during non-work hours. Stop your email alerts and avoid checking or responding to work-related messages outside of work hours. This detachment can promote good sleep and mental health by halting the process of resource drain commonly experienced as a result of workplace stress.

2. Relaxation: Relaxation can be experienced in a number of ways, including reading, listening to music, or taking a walk.

3. Mastery: Mastery experiences are those that are challenging and provide an opportunity for learning or growth, like playing a sport or learning a new language. These are important for promoting well-being and maximizing performance, both at work and at home.

"Engaging in recovery experiences like psychological detachment and relaxation can help maintain one's well-being in the face of persistent workplace incivility, though it will not eliminate the workplace incivility itself," Demsky says.

In her 2019 study, employees who practiced these techniques regularly were able to mitigate the negative effects of work incivility on sleep. They relaxed, recharged, and slept well after work. They were better able to handle rude coworkers.

How to build a civil workplace

1. Take employee complaints seriously and investigate the source. While some offenses may seem like "no big deal," they may actually be damaging employees' mental health. This may require having "difficult conversations" with employees, Demsky says, who may or may not be aware that their behavior is being perceived as uncivil.

2. Take the temperature. Workplace incivility can occur as a result of workplace stress, Demsky explains. Provide social support and resources for employees, which can help reduce this stress, and in turn, prevent workplace incivility.

3. Set an example. Modeling, communicating, and rewarding appropriate civil behavior can also go a long way towards creating a civil workplace environment, Demsky says.

4. Address it directly. If you're dealing with repeated rude behavior, try discussing it with the perpetrator, if that is feasible. In situations where a direct conversation isn't possible, seeking outside support and discussing the problem with a supervisor is recommended, Demsky says.

“Shifting the messaging to ‘toughen up and deal with it’ can be seen as placing the sole responsibility for incivility on victims,” Demsky says. “In reality, organizations and managers have a responsibility to provide a safe workplace and reduce the behavior in the first place.”

This article was originally published on