Gut microbiome study reveals the depths of racial health disparities

Time for a gut check.

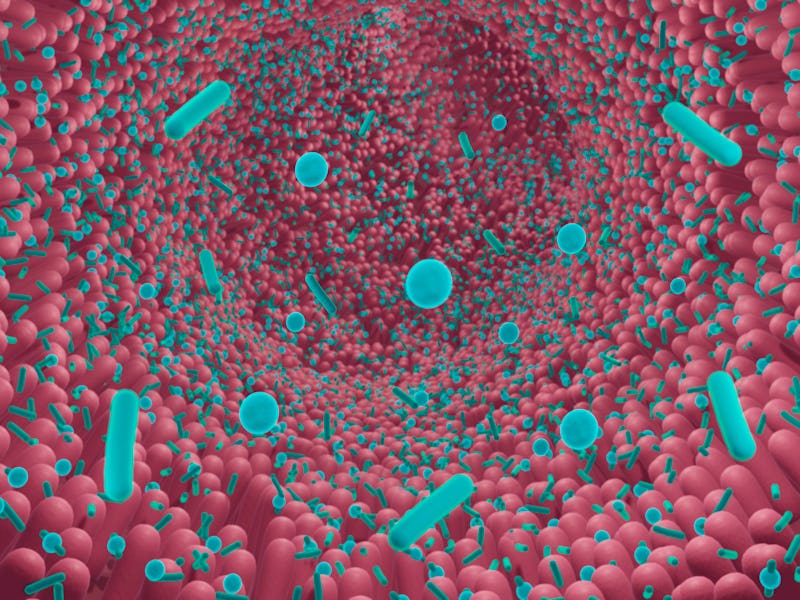

The gut microbiome — the myriad microorganisms, viruses, and fungi living in your G.I. tract — is the new frontier in understanding and safeguarding human health. But a new study suggests it may also reveal new information about health disparities, and how to treat them.

What’s new — In a paper published Wednesday in PLOS ONE, researchers reveal how health disparities between Black and white women in the U.S. manifest themselves in the gut microbiome. The researchers found clear differences in the women’s gut bacteria populations. The finding adds to the evidence that environmental factors help create and perpetuate unequal health outcomes along racial lines.

Over the last 15 years, scientists have sought to map the human microbiome, the totality of the hundreds of thousands of microorganisms living in the digestive tract. Studies show the microbiome is linked to obesity and diabetes, as well as non-metabolic conditions, like cancer and neurodegenerative diseases.

“What’s so fascinating about the microbiome is that it differs a lot within each individual, and that’s determined by their outside environmental factors.” the study’s lead author Candice A. Price tells Inverse.

“This might include things like their diet, their air quality, their psychological stress. The microbiome is kind of like an insight into the biological effect of these environmental factors,” she adds.

Why It Matters — Stark differences in the gut microbiome between two groups of people can indicate stark differences in their environment.

Black women in the U.S. have higher rates of metabolic health problems than white women. According to the Centers for Disease Control, 45.1 percent of Black women are classified as obese, compared to 24.5 percent of non-Hispanic white women, and 12.7 percent are diagnosed with diabetes, compared to 7.5 percent of non-Hispanic white women.

As with any racial health disparity, untangling the reasons behind these health differences requires investigating how inequality and systematic racism intersect and manifest themselves upon the human body.

Black communities in the U.S. typically have less access to healthy foods, live with poorer air quality, and exist under greater social stress, all of which play a role in health Price says.

“All these social determinants of health, as we call them, are really related to these health disparities, but we don't quite understand how,” she says.

The gut microbiome offers a new area for therapeutics and medicine. But in order for those treatments to work effectively for everyone, researchers need to study the gut microbiomes of many different groups.

Air quality, which negatively affects urban areas, like Los Angeles (pictured), is a known factor connected to racial health disparities in the U.S.

How they did it — In the study, which included 94 Black and 74 white women, the researchers found that while the microbiomes of Black participants were similar to each other, and the microbiomes of white participants were akin to each other, the two groups were distinctly different from each other.

That there was a difference is a significant finding on its own, says Price; it shows the extent to which one set of environmental factors affects Black women versus white women.

“The microbiome is kind of like an insight into the biological effect of these environmental factors.”

For example, black women had a greater abundance of actinobacteria, which is a phylum of bacteria associated with inflammation.

“Many studies demonstrate that inflammation is higher in black women as compared to white women,” Price notes.

Begun in 1985, the study recruited 2,379 girls, aged 9 and 10, hoping to track the development of obesity and cardiovascular disease and evaluate risk factors. Half of the girls were Black and half white. The study is ongoing.

For the new study on gut microbiomes, researchers sought volunteers from this population willing to submit stool samples. They found that the body mass and fasting insulin were significantly greater in Black women. Almost half of the Black women were insulin resistant, compared to 30 percent of the white women. These factors alone could account for microbiome differences, so they adjusted the analyses to account for that.

What’s Next — Price does not have any new microbiome studies planned, but she says the possibilities are extensive. The gut microbiome could be measured in an intervention study, trying to show the benefits of a dietary approach. There are also nasal and vaginal microbiomes that could reveal findings on health inequity.

The study also tried to factor in insulin sensitivity and resistance. Insulin sensitivity refers to how well the body responds to insulin. High insulin sensitivity is a sign of good metabolic health while poor insulin sensitivity, known as insulin resistance, can be a precursor to diabetes. Among women with high insulin sensitivity, Black women had twice or four times the amount of some types of bacteria, but the significance of this — other than demonstrating again that the two groups face different health environments — is not yet known.

What these differences mean for metabolic health — and why they exist — will require more research to tease out. The scientific investigation into the microbiome is relatively new and the gut still holds many secrets.

Abstract: The prevalence of overweight and obesity is greatest amongst Black women in the U.S., contributing to disproportionately higher type 2 diabetes prevalence compared to White women. Insulin resistance, independent of body mass index, tends to be greater in Black compared to White women, yet the mechanisms to explain these differences are not completely understood. The gut microbiome is implicated in the pathophysiology of obesity, insulin resistance and cardiometabolic disease. Only two studies have examined race differences in Black and White women, however none characterizing the gut microbiome based on insulin sensitivity by race and sex. Our objective was to determine if gut microbiome profiles differ between Black and White women and if so, determine if these race differences persisted when accounting for insulin sensitivity status. In a pilot cross-sectional analysis, we measured the relative abundance of bacteria in fecal samples collected from a subset of 168 Black (n = 94) and White (n = 74) women of the National Growth and Health Study (NGHS). We conducted analyses by self-identified race and by race plus insulin sensitivity status (e.g. insulin sensitive versus insulin resistant as determined by HOMA-IR). A greater proportion of Black women were classified as IR (50%) compared to White women (30%). Alpha diversity did not differ by race nor by race and insulin sensitivity status. Beta diversity at the family level was significantly different by race (p = 0.033) and by the combination of race plus insulin sensitivity (p = 0.038). Black women, regardless of insulin sensitivity, had a greater relative abundance of the phylum Actinobacteria (p = 0.003), compared to White women. There was an interaction between race and insulin sensitivity for Verrucomicrobia (p = 0.008), where among those with insulin resistance, Black women had four fold higher abundance than White women. At the family level, we observed significant interactions between race and insulin sensitivity for Lachnospiraceae (p = 0.007) and Clostridiales Family XIII (p = 0.01). Our findings suggest that the gut microbiome, particularly lower beta diversity and greater Actinobacteria, one of the most abundant species, may play an important role in driving cardiometabolic health disparities of Black women, indicating an influence of social and environmental factors on the gut microbiome.