In 2020, five studies demystified essential human experiences

This year neuroscience tackled stress, empathy, loneliness, consciousness, and death.

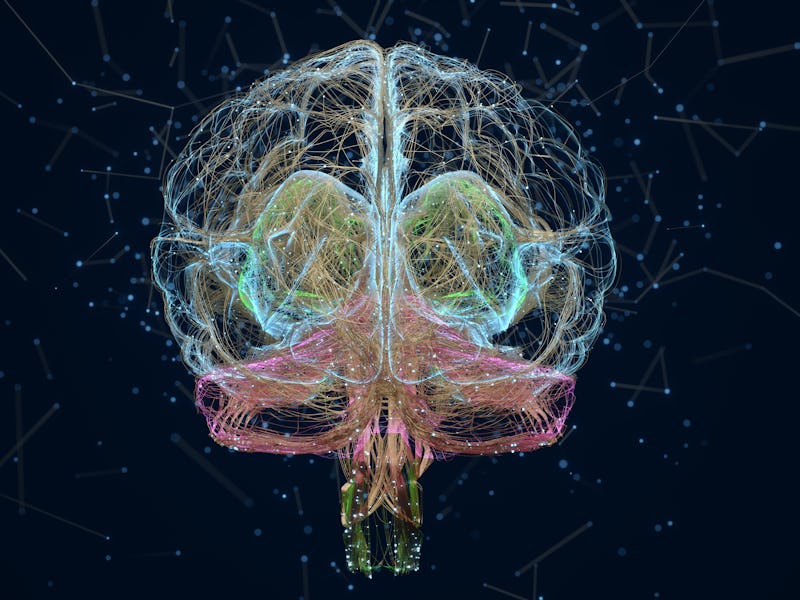

Scientists are making progress in mapping the world inside our brains.

New findings published in 2020 on the inner workings of our extremely complicated brains gave us critical insight into how and why we feel, how our actions leave lasting impacts on our bodies, and what forces drive our experience of the world.

It was a busy year for brain science. Further studies, all published despite the pandemic, suggest how the brain responds to stress, what we hear as we die, where consciousness may begin, and revealed the toll of loneliness.

Here are five findings Inverse reported on that blew our minds:

1. The link between exercise and stress

In August, scientists clarified a mountain of research suggesting exercise can help manage stress. In their mouse-based study, they found that a neuropeptide called galanin may be partially behind the effect.

The mice in the study were given free access to a running wheel and over the course of three weeks, the mice increased their running distance to about 10 to 16 kilometers per day. Compared to controls, the mice who exercised were more resilient to a stressful event (a foot shock).

They also had higher levels of galanin in a cluster of neurons near the brainstem called the locus coeruleus, which is involved in stress responses.

Regular exercise may increase resilience to stress thanks, in part to the action of one neuropeptide: galanin.

When the team genetically engineered sedentary mice to express similar levels of galanin to the runner mice, those mice also proved to be more resilient to the foot shocks.

The takeaway for humans, the study’s authors told Inverse, is that regular exercise helps us cope with stress when it inevitably surfaces.

Read the researcher’s full takeaways here.

2. The search for consciousness leaps forward

A February study suggests that the “engine for consciousness” may actually be a tiny area of the brain called the central lateral thalamus.

In an experiment described in a paper published in Neuron, scientists put macaque monkeys under anesthesia and then zapped their brains with electrodes at a frequency of 50 hertz.

When the team happened to zap the central lateral thalamus, the sleeping monkeys sat up, as if fully conscious, and their brains showed patterns of activity typically seen during consciousness.

“The animal went from being deeply anesthetized to opening his eyes, looking around the room, and even reaching out for objects within only a few seconds of the stimulation turning on,” co-author Michelle Redinbaugh, a researcher at the University of Wisconsin Madison, told Inverse.

Once the stimulation ended, the monkeys fell back asleep.

Consciousness is a complex phenomenon that likely comes down to more than one area of the brain, but this study suggests that we one day might find distinguishable neural pathways that underpin our whole experience of life.

Read more about what this study means for the future here.

3. Heavy drinking can put the brakes on empathy

Empathy for others, or the ability to feel another’s pain can be as painful as it is important, especially in the midst of a global catastrophe. But heavy drinking, which is one way people deal with pandemic stress, can make it harder to feel another’s pain, according to a study released in September.

Scientists at the University of Sussex took fMRI scans from 71 participants, half of whom were categorized as binge drinkers because they drank the equivalent of about three quarters of a bottle of wine (or 2.5 pints of beer) in one sitting in the past 30 days.

Binge drinking may make it more difficult to feel empathy.

While scientists scanned everyone’s brains (all subjects were sober) the subjects saw images of a limb being injured, and were asked to imagine that the limb belonged to them or someone else. The binge drinkers found it harder to adopt another person’s perspective in the experiment.

The binge drinkers also saw activation in a visual area of the brain involved in recognizing body parts when they were imagining the pain was someone else’s (rather than their own).

Read more about the connection between binge drinking, and empathy here.

4. The last thing the brain hears before death

Even once a loved one is no longer conscious, they may hear the final words spoken to them at their bedside. That’s according to a study released in June, showing that our final words don’t fall on deaf ears.

This finding comes from a sample of 17 healthy control patients, and 13 patients in palliative care: eight responsive patients, and five non-responsive patients.

The scientists played a series of five-note songs at each person’s bedside. The patients who could respond were asked to count which songs included tonal changes, and which didn’t, while scientists measured electrical activity in their brains.

Those who couldn’t respond, simply listened.

Even the five unresponsive patients showed a key pattern of brain activity that was also present in the responsive patients: a quick dip in activity following the tone changes.

While that dip may not be a sign of consciousness or even understanding (the scientists are unsure on that front), the study authors told Inverse that this is a sign that a loved one may still actually hear things from this world as they pass away.

“I would say it is possible — but certainly not proven — that at least some patients, some of the time, can comprehend what loved ones are saying to them, or even what is being said around them when they are unresponsive,” Lawrence Ward, the study’s senior author and a professor at the University of British Columbia, told Inverse.

Read more about how the brain “hears” its last words here.

5. Loneliness changes the brain

In a pandemic year defined by social isolation, scientists found that loneliness may physically reshape the brain.

Yellow areas of the brain had higher grey matter volume in lonely people, green areas showed lower grey matter volume. But overall, lonely people had more grey matter volume in the areas of the default mode network.

In a study on 38,701 brain scans pulled from the UK biobank, a team of researchers at McGill University found that loneliness was linked to three major changes to a circuit called the default mode network, which lights up when we dwell on the past, plan for the future, or daydream.

Those changes included:

- An increase in grey matter volume in the areas of the brain within the default mode network

- More structural integrity in the fornix, a bundle of nerve fibers that carries signals from the hippocampus to the default mode network

- Greater connectivity in that network overall

Taken together, study author Nathan Spreng told Inverse these changes could be the brain’s adaptation to the loss of a social environment. The brain “compensates” by fortifying the circuit that helps create our inner worlds.

“Lonely people tend to imagine the social world to a greater degree, as well as reminisce about social experiences more," Spreng explained. "We think that in the absence of social stimulation in the world, the brain is compensating by up-regulating these functions of the default network.”

However, he also indicated that these changes might be reversible.

Read how this research relates to the pandemic (and its aftermath) here.

This article was originally published on