How fasting changes your gut microbiome

The timing of eating matters.

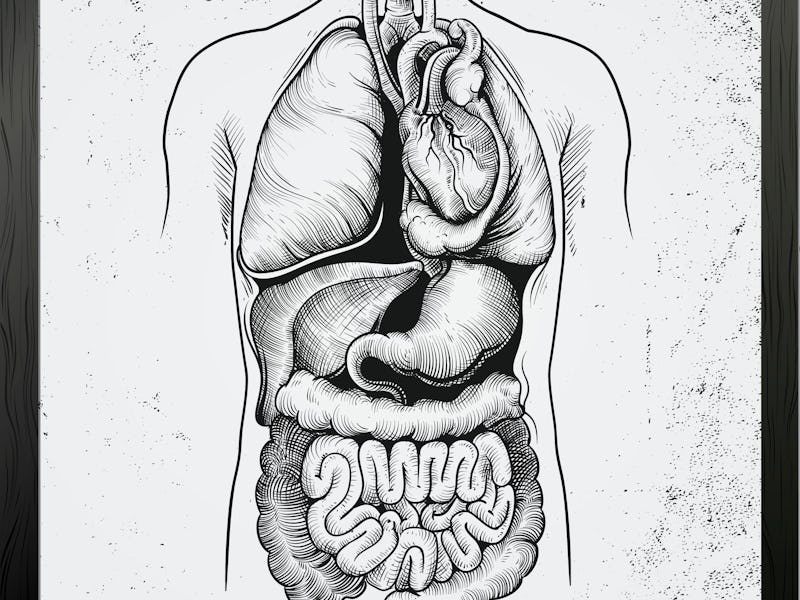

Little living things deep in our bowels hold a mysterious grasp on the balance within our bodies. One change to our food regimen — what we eat, how much of it, and when — and the biological harmony can be thrown off.

This we know. What don’t know is exactly how the tiny microbes that make up the gut microbiome harness their power. This knowledge is necessary for truly understanding what fasting does to the gut microbiome.

But in the meantime, animal studies on intermittent fasting’s effects on the gut microbiome do suggest the eating pattern could eventually be used for good — potentially as a treatment for diabetes, a way to boost immunity, and a way to transform “bad fat” to “good fat.”

What you should know first — While these studies are promising, there’s a caveat: They’re mostly from mice. These ideas aren’t validated by human studies, also known as clinical trials.

“If you look at it closely, there's clearly a deficiency in many areas of this microbiome field, a deficiency of well-controlled, randomized controlled studies in humans,” Dr. Emeran Mayer tells Inverse.

Mayer co-authored a 2021 review published in the journal Nutrients on the relationship between intermittent fasting and gut health as it relates to weight loss. He’s a professor at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and runs the UCLA Brain Gut Microbiome Center.

This discrepancy is because mouse and other animal studies lay the groundwork for studies in humans: they are shorter, less resource-intensive, and serve as a sort of filtering mechanism to rule out some theories and advance those most likely to translate to human bodies. The field is still emerging, so there have been fewer of these high-quality human trials.

And while there’s strong evidence that certain kinds of fasts can help with preventing heart disease, diabetes, high cholesterol, regulating blood glucose, and helping blood pressure, it’s not clear exactly how — or to what extent — the microbiome is involved.

“If [intermittent fasting] helps your microbiome and sleep and appetite, makes you less hungry — none of that stuff has been shown just yet, so I say the jury's still out on that,” Krista Varady tells Inverse. Varady is a professor of nutrition at the University of Illinois, Chicago, who has studied intermittent fasting in humans for the last 15 years.

Few robust human studies so far have investigated changes in the gut microbiome from fasting and their effects. Everyone’s microbiome is different, Mayer says, meaning everyone can react differently to fasting.

The research published so far points toward preliminary links between the gut microbiome and cardiovascular markers of health, diabetes, and metabolic regulation.

Microbes aren’t limited to our intestines - and fasting can affect the way they’re distributed across the digestive system.

Fasting and the gut microbiome

To truly understand whether or not fasting causes a shift in gut flora, scientists have to establish something else: that a change in our gut actually happens when we fast. Research here is preliminary, but so far studies point to a delicate balance, or homeostasis, in our gut composition that can change in response to what and when we eat.

This balance might interact with other parts of our body — signals to our brain, circadian rhythms, exercise regimens, genes — in ways that are not yet fully understood.

In one study, researchers found mice who fasted for period periods of 16 or 20 hours saw increases in Akkermansia — a genus of bacteria known to be “beneficial” — and decreases in another genus, Alistipes, which play different roles in the body but is linked to regulation of certain diseases and inflammation. After the fasting period, this effect on the microbes ceased.

In another study, people who practiced time-restricted feeding on a 16:8 pattern (16 hours of fasting, 8 of feeding) experienced no significant difference in gut microbiome composition.

Sofia Forslund, who studied the effects of a longer fast in another study on human participants, previously told Inverse fasting is perhaps “a controlled challenge or controlled the insult to the system that allows it to adapt and regain homeostasis — and that involves both the microbiome and the host.” The mechanics of just how, however, are unclear.

A 2021 review on fasting and the microbiome as it relates to weight management noted that changes in the gut microbiome are also somewhat resistant to temporary dietary changes in general. You’d have to stick with a dietary shift for a long time — and likely, a long fast — to see a lasting effect on your guts’ population of bacteria, and theoretically, any health benefit that could come from that effect.

Microbiome changes and cardiovascular health

Slightly more compelling evidence for the benefits of fasting and the microbiome point toward its effects on blood pressure. High blood pressure can lead to a host of other concerns, including an increased risk of stroke and heart attack.

In a study published in February, researchers tried out intermittent fasting on stroke-prone rats with high blood pressure. Compared to similar rats who could eat whenever they wanted and those that were fed every other day, rats who fasted showed reduced blood pressure. The researchers found microbiomes were involved in the change by transplanting both kinds of microbiota into “germ-free rats.” They subsequently observed that the rats who received the fasted-rat microbes had lower blood pressure.

In a 2021 trial in humans, scientists examined how fasting for five days affected participants beginning a Mediterranean diet. They found that gut microbiota underwent significant changes, and their blood pressure went down even three months after the diet change. Participants even decreased their hypertension medication. The study team thinks these changes were influenced by the fast, and not just the diet they began.

Microbiome changes with fasting and diabetes

Animal studies have shown significant improvements in diabetes-related problems that were linked to their microbiome — but what works on mice might not work in humans. For example, in one study, mice on an intermittent fasting diet saw changes in their microbiome that were linked to a reduction in the cognitive impairment related to diabetes.

In another, researchers found that intermittent fasting (every other day) restructured the gut composition in mice enough to prevent a common complication of diabetes, retinopathy, or damage to the vision. What’s more, the mice lived longer.

Microbiome changes and metabolic health

The relationship between fasting, microbes in the body, and metabolism is a complex one that goes beyond just the composition of microbiota in feces — one of the more common ways to study the gut in humans.

Mayer says that the movement of the human digestive system, as well as where the microbes are located, also make a difference. For example, microbes get further away from the gut lining during fasting, Mayers says. In animals, he said, “that has been associated with better metabolic health, the distribution of this microbial geography in the GI tract.”

One study that fed mice every other day found that the changes in their microbiome led to more healthy “brown fat” and lowered obesity, which is associated with improvements in metabolic syndrome.

On the other hand, a small study in human patients with obesity showed that while time-restricted eating did lead to a small loss of body weight (different from fat mass), there were no significant changes to their gut microbiome composition from the intervention.

Ultimately, Mayer says, “as a treatment for metabolic syndrome, exercise, and this time-restricted eating are the things that I recommend to my patients at the moment, even before the definitive human studies all come out — because everybody can do that.”

This article was originally published on