Antibody-resistant Covid-19: How it works

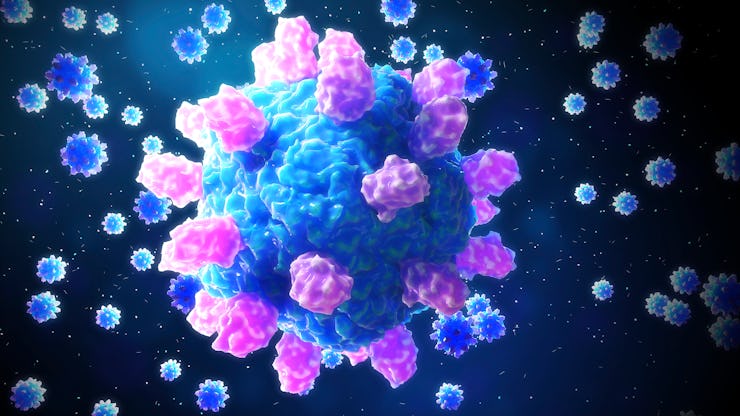

Here’s how antibodies stop spike proteins from unlocking your cells.

When a new strain of Covid-19 appears, an immediate question for more than 50 percent of the U.S. population is: Will my vaccine protect me against this new variant?

We are really asking are two questions when this occurs:

- Will I get breakthrough Covid-19?

- If I do become infected, how likely am I to have a severe or even fatal case?

The answers come down to how our immune system cooperates with vaccines. We typically think of antibodies as the star of the vaccine-immune system show, and for good reason: They’re critically important. But the immune system produces other cells to fight foreign pathogens.

Understanding how all of these interact together in response to a vaccine is vital to separating hyperbole from fact when it comes to phrases like “antibody” or “vaccine resistance.”

What “antibody resistance” means

Medical experts use “antibody resistance” to describe what happens when a variant evades some of the antibodies your body produces, either after vaccination, or past infection of the same virus.

“When we’re saying either ‘antibody’ or ‘vaccine-resistant,’ we just mean that your antibodies don’t neutralize all of the virus the way you would hope if it was working perfectly,” William Schaffner, an infectious disease specialist at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center, tells Inverse.

“You’re killing the cells that are already infected, and you’re protecting the cells that are not infected.”

In the context of vaccines, antibody resistance can mean:

- A vaccinated person might be more likely to become infected with the variant than the original virus.

- A vaccinated person might be more likely to become infected and experience symptoms.

- A vaccinated person might be more likely to become infected and experience severe disease or death.

These scenarios lay out a critical comparison: Exposure to the variant versus exposure to the original virus.

Vaccinated people are still far less likely to experience any of those things — especially the worst outcomes — than unvaccinated people. That’s why in places like Virginia, unvaccinated people are 12.3 times more likely to end up in hospital with Covid-19 than fully vaccinated people.

To understand the science behind this reality, you need to know what happens to our bodies after getting a vaccine.

Getting a Covid-19 vaccine is now more critical than perhaps any other time.

How coronavirus vaccines work

When you’re infected with a virus, your body’s immune system knows to attack it because of proteins on the virus called antigens. Immune cells called antibodies are proteins that are specifically designed to bind to these antigens. When that happens, it signals to the rest of the immune system, including T-cells, to find and destroy the foreign pathogen.

On the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the antigen is called the spike protein — it’s the “key” that the virus uses to unlock and enter cells. Vaccines give your body a cheat sheet to make the antibodies bind to the specific virus antigen.

If you contract the virus, there’s no guarantee your immune system will be able to fight it. SARS-CoV-2 is especially tricky because people tend not to have symptoms for a few days after infection — giving the virus time to replicate over and over. This can overwhelm the immune system and lead to severe illness and complications like long Covid.

See also: Inside a Covid-19 support group, where a long-haul future is faced head-on

Meanwhile, the antibodies produced by a Covid-19 vaccine are significantly more robust than those incurred via “natural” immunity.

Donald J. Alcendor, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology at Meharry Medical College, tells Inverse that robust antibody response is important: “When antibodies are in sufficient quantity, they can effectively block entry of the virus into a cell.”

The unsung hero of vaccine immunity — Although they get all the glory, antibodies aren’t the only thing stimulated by a vaccine. While antibodies identify foreign pathogens and attach to their antigens, other cells are at work.

If you think about your immune system as a team of fighters, some are very specialized in what they do,” Alcendor says.

Those are the antibodies — the Navy SEALs of the body. They know exactly what to look for and how to block the virus from getting into your cells.

But there will be cells that are already infected, Alcendor says, and we need fighters for those cells. That’s where T-cells come in — the cavalry.

“Cytotoxic T-cells are designed to seek out and to kill infected cells,” he says.

So the immune response does two things. “You’re killing the cells that are already infected, and you’re protecting the cells that are not infected from becoming infected,” Alcendor says.

How “antibody resistance” works

As viruses mutate, those mutations can include all or part of the antigen. With some coronavirus variants like the Lambda variant, we know there are several mutations to its antigen — the spike protein it uses to get into human cells.

Antibodies are a security guard told to watch out for one specific burglar — the variant, except now it is wearing a hat, glasses, and fake mustache. The disguise will not fool most security guards — but sometimes, the variant may still slip past. If the assault is strong enough, it can cause infection and symptoms.

The chances of that happening increase in two scenarios:

- People who produce weak immune responses to vaccines

- People who are older or immunocompromised are going to produce less robust immune responses.

As Alcendor says, “for a person who is 75 years old, their immune response is also 75 years old.”

In this older body, the security guard might be a little less sharp than he used to be and more likely to be fooled by the disguise. So when they talk about breakthrough infections, scientists are most concerned about older or immunocompromised people.

We don’t know exactly how long the Covid-19 vaccines last, but antibody strength decreases over time. That’s why some vaccines require boosters, like MMR or tetanus.

Antibodies aren’t the only security team in your body. You also have T cells trying to kill any infected cells, albeit in a less focused way.

Schaffner speculates that this may explain why Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna advocate for boosters based on their in-house data. Most people in the U.S. who are fully vaccinated with an mRNA vaccine will be given the chance to get a booster shot eight months after they received the second dose of the vaccine, according to the CDC.

“There’s a distinction between the antibody levels you’re seeing in a lab and what’s actually happening in the field,” Schaffner says.

New variants of the coronavirus may have mutations in the spike protein — the key the virus uses to unlock the body’s cells.

Booster shots and vaccine resistance

For the most part, lab tests only look at antibody titers. To determine how well T-cells and antibodies are working together as a team, Schaffner says, “We look to the field.”

“The field” is the vaccinated population. So few vaccinated people are ending up in the hospital with Covid so far, and that’s a good sign that our T-cells are still doing a great job of backing up our antibodies.

See also: Covid-19 booster shot: Schedule, side-effects, concerns, and usefulness

“So far, the vaccines are protecting against serious disease. That’s what they were designed to do. And we’re about nine months into vaccinations and the vaccines are hanging in there,” Schaffner says.

The immune system is complex, and SARS-CoV-2 is a wily adversary. The efficacy of vaccines in protection from infection and severe disease does drop when up against an antibody-resistant variant. That’s why people who are not in the medical or life sciences field often refer to them as “vaccine-resistant” variants.

It is also why the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recently set a date for vaccine booster shots for the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines starting mid-September for those at the top of the line — many months after individuals received their initial dose in the early part of 2021.

But if we leave you with anything, let it be this: An antibody-resistant variant does not mean your vaccine does not work.