Covid-19 could cause a different disease in previously healthy people

Recent studies from England and other countries have suggested that adults with both types 1 and 2 diabetes have an increased risk of death if they catch Covid-19, especially if they have poor glucose control. The weight of evidence is building up to support this theory. And when the dust settles, a more critical analysis of the data will probably confirm this increased risk.

But in early June, several well-respected academics from around the world wrote a letter to the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) suggesting that Covid-19 is not just a risk for people with diabetes – it may actually cause diabetes.

There are two main types of diabetes. Type 1, caused by the body’s own immune system attacking the islet cells in the pancreas that produce insulin, a so-called autoimmune disease. Eventually, there are no islets left and hence no insulin can be made to control blood glucose levels. We don’t know what starts this autoimmunity, but viral infections have been suggested as a possible trigger.

Type 2 diabetes happens when the islet cells have to produce vast amounts of insulin because the main target organs (liver, muscle, fat) do not respond as well as they should to insulin’s message. Finally, the islet cells become exhausted and die.

We have known for many years that viral infections may be linked to the first time a patient has diabetes symptoms. (Type 1 diabetes presents in a seasonal fashion, a fact often seen with viral infections.) And viral infections may also trigger the destruction of the insulin-producing islet cell “factories” in the pancreas, setting up a chronic autoimmune response.

There are recorded cases of acute diabetes developing during mumps and enterovirus infections. And there is significant evidence linking one particular enterovirus, Coxsackie-B1, with classical autoimmune type 1 diabetes. In addition, The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study from the US and Europe documented an increased risk of developing signs of islet cell autoimmunity after respiratory infections caught in the winter months.

There’s something about coronaviruses

What about Covid-19? There has been a case report from China of a young man of previous good health presenting with new-onset, severe diabetes, termed keto-acidosis, after contracting Covid-19.

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, east Asia experienced the Sars outbreak (2002-04), which was also caused by a coronavirus. There were documented cases of acute onset diabetes in people with Sars pneumonia, which was not seen in those with pneumonia of other causes. In most cases, diabetes resolved after three years, but it persisted in 10% of patients.

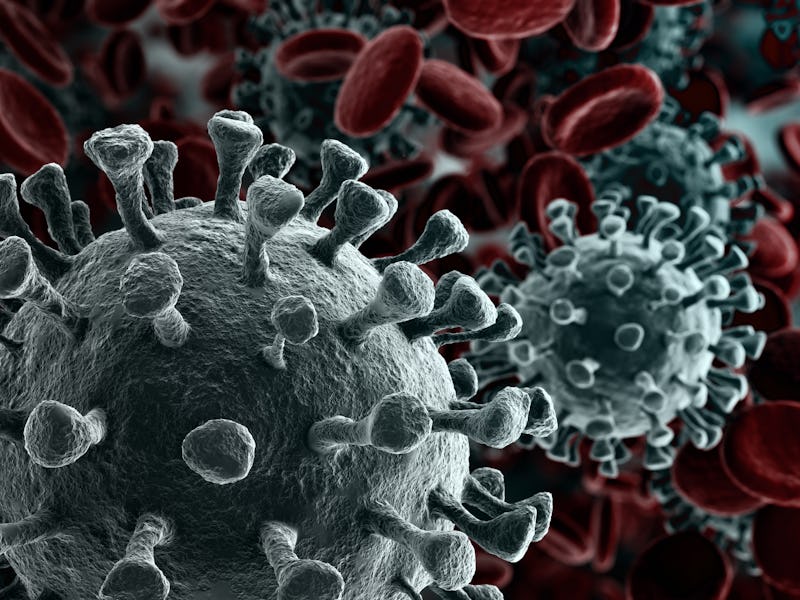

The coronaviruses responsible for the current and previous outbreaks share a similar way of getting into cells. The now-familiar protein spikes on the surface of the virus attach to ACE2 receptors are abundant in lung, kidney and islet cells in the pancreas. It is proposed that once in islets, Covid-19 disrupts normal cell function leading to abnormalities in the pathways that maintain blood glucose through insulin secretion. It is also possible that cell invasion leads to acute inflammation that kills islet cells.

Spike proteins (S) are in red. Orpheus FX/Shutterstock

So does Covid-19 cause diabetes? The answer is, we don’t know, and the NEJM letter makes it clear that a lot of this is still conjecture. Covid-19 may trigger type 1 or type 2 diabetes. This might even be a new form of diabetes.

Unlike the wealth of data presented on the risk of death with known diabetes, severe obesity, high blood pressure, and ethnicity, there is little data on Covid-19 and newly diagnosed diabetes. To address this, the authors of the NEJM letter have developed a register to record all Covid-related diabetes cases.

A register is essential to gather enough data to start unraveling the mystery of any direct link between Covid-19 and diabetes. And if such a link is found, it will be equally important to determine how Covid-19 causes the damage to best identify treatments, given that Covid-19 may be around for quite some time yet.

This article was originally published on The Conversation by Julian Hamilton-Shield the University of Bristol. Read the original article here.

This article was originally published on