America is stuck in the first Covid-19 wave because 2 crucial events never happened

The first wave of coronavirus never ended. Here's how scientists know.

Americans have heard warnings of a second wave of Covid-19 since March when it became clear that the virus would shape our lives for the foreseeable future. Now, as the United States witnesses coronavirus cases rise, experts are warning that this isn't the second wave people have been waiting for.

The US never got out of the first wave, because two important developments never happened nationwide.

There's actually no epidemiological definition of "wave" Chris Bauch, a professor of applied mathematics at The University of Waterloo, tells Inverse. The phrase "wave" is simply a way of describing a trend in cases. Still, waves tend to be defined by three distinct characteristics.

"When epidemiologists use the term 'wave,' they usually mean a situation where cases rise, peak, and then fall significantly," says Bauch.

On Friday the US saw 40,173 new Covid-19 cases nationwide — the highest in a single day since the pandemic began.

That might make it seem like that "second wave" is about to swallow us whole. But the first wave has to end before the second can begin and that never actually happened explains Loren Lipworth, a professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University.

"I think it's important to know that this is just a continuation of the first wave," Lipworth tells Inverse. "It's not a second wave."

The US is still riding that first wave out because the two crucial developments that signal the end of a wave haven't come to pass:

- Cases have to drop significantly – not simply flatten out.

- Cases need to stay down for extended periods of time.

What does a significant drop in cases look like? – Ideally, we need to see coronavirus cases in the United States taper off far more than they ever actually did — even before we saw this new increase.

"If you look at some of the curves of new daily cases, they've only declined in the US, say, by about a third," Lipworth explains. "We had this really high peak in March, and even at this most recent point across the US, we're not back to the low point at all."

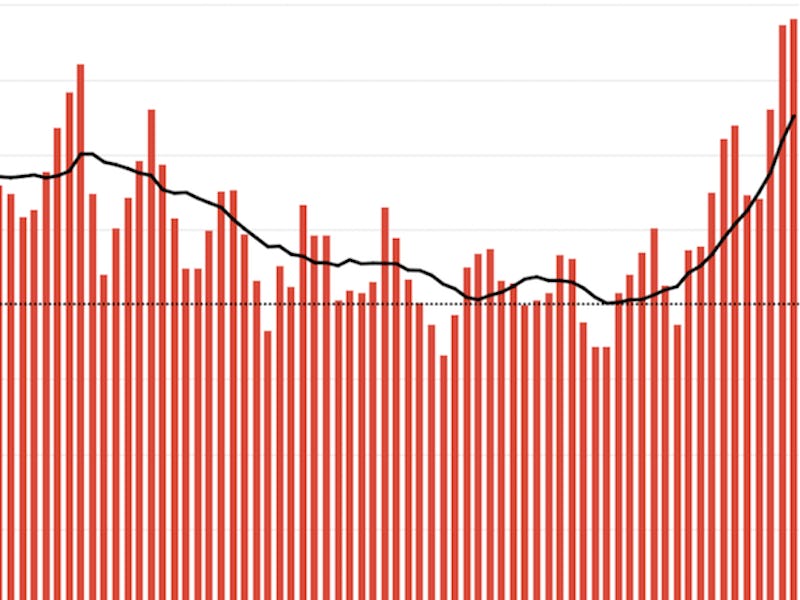

The nationwide count of daily positive coronavirus cases from March through June 25.

A flatter curve doesn't mean the end of a wave – the number of new positive cases must plummet

How low cases have to go will vary by state, and differ even more when you're looking across an entire country. But to get a sense of what the shape of a plummeting curve should look like, take a look at New York, Connecticut, and New Jersey, Lipworth says.

New York's coronavirus cases have steeply dropped off. In past two weeks (seen in green, far right) cases have continued to trend down.

"If we look at a curve across the US, our curve is not down the way it is in New York and New Jersey," she says.

That said, even if you look at New York's curve, it's still not certain that the first wave has officially ended – despite a drastic downturn. Those cases must stay down before the end of wave one can be declared, and Lipworth says that it's too soon to tell if they're going to keep trending downwards.

We also can't say how many days, weeks, or months must elapse before we know for sure that the wave has ended. But if we continue to watch the progress in New York, Connecticut, and New Jersey, we may get a better idea of how we can both start to reopen and keep cases low.

Not a second wave, but a new surge – In the rest of the country, we need to focus on getting the cases to drop off in the first place. Mistaking the new rise in cases for the second wave of coronavirus obscures a crucial point: nationwide, we failed to truly contain Covid-19.

If you look at the wave of coronavirus cases regionally, you see a similar rise, spike, and decline in the Northeast region. This is not seen in the South and West, where cases rose rapidly — the emergence of the wave — but never significantly dropped.

Regional differences in new coronavirus cases.

These spikes partially have to do with timing, says Lipworth. The coronavirus was never going to hit the whole country at exactly the same time, with the same intensity. But the prolonging of the first wave, she adds, comes down to human behavior.

For instance, experts know that face masks help control the spread of coronavirus. A study released in early June suggests that if 50 percent of Americans actually wore them, then the number of people one person with coronavirus might infect would drop below one (the amount needed to flatten the curve). If 100 percent of people wore them (and we practiced intermittent lockdowns) we might prevent a surge in cases for 18 months.

"The more we help out now, the lower the transmission rate will be and the lower the positivity rate will be in our current population," Lipworth adds. "Hopefully that will lead to the regression of the current wave the way we've seen in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut."

Ending our struggle with the first wave needs to happen sooner rather than later, says Lipworth. The better we control it now the better off we might be later, when that real second wave does arrive.

This article was originally published on