What does Covid-19 do to the brain? Neuroscientists split fact from fiction

"The sheer variety of symptoms that people are experiencing is mind-boggling."

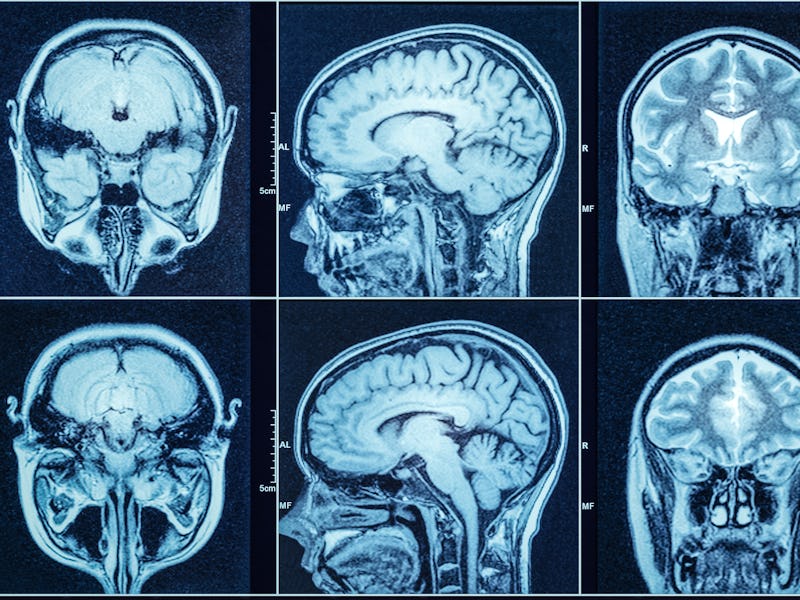

The coronavirus can cause strange, disorienting effects on the brain, from the moment of infection to months after one's last positive test.

"The sheer variety of symptoms that people are experiencing is mind-boggling," Andrew Levine, a neuropsychologist and clinical professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, tells Inverse. "So the question is: How can this be?"

Levine has chased the answer to that question for months, striving to pin down the prevalence and symptomatology of what he calls "neuro-Covid."

While initially considered a primarily respiratory illness, burgeoning case reports and scientific studies make one thing clear: Covid-19 can affect the brain in mysterious and devastating ways.

Covid-19 and the brain: Who is at risk

When people become sick with Covid-19, most experience the hallmark symptoms: fever, fatigue, shortness of breath, or dry cough. Others can experience less common symptoms that link back to the brain: smell and taste loss, headaches, memory loss, dizziness, and confusion.

In severe cases, people suffer from encephalopathy or global brain dysfunction, brain inflammation, post-traumatic stress disorder, seizures, stroke, or even death.

The specifics of how likely a person sick with coronavirus is to develop neurological symptoms range per study, but robust analysis of 4,491patients published in the journal Neurology in October found that 13.5 percent developed a neurological disorder in a median of 2 days from Covid-19 symptom onset. This equates to about one in seven people infected with coronavirus developing brain issues.

Meanwhile, a study published in April in Jama Neurology found that 36.4 percent of 214 hospitalized patients had neurological symptoms; a study published in October in the Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology found 82.3 percent of 419 hospitalized patients experienced the same.

Crucially, the neurological effects of coronavirus are something most people infected with the disease will not experience. Instead, it is a concern for those who have to be hospitalized post-infection. The patients most likely to show brain-related symptoms are those with severe Covid-19, Levine says.

"The vast majority of people that become infected with SARS-CoV-2 are not going to experience any sort of neurological symptoms," Levine says.

Covid-19 and the brain: The symptoms

Eric Liotta is a neurologist at Northwestern who has treated Covid-19 patients like these first hand. Liotta is involved with the Neuro Covid-19 Clinic at Northwestern Memorial Hospital.

"Covid-19 isn't just a pulmonary disease," Liotta tells Inverse. "The whole body can suffer as a result of complications."

Liotta is a co-author of the study published in the Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology. His team analyzed the neurologic manifestations in a group of 509 Covid-19 positive patients admitted to the hospital in Chicago.

The team found that 42 percent of patients had neurologic manifestations at the onset of Covid-19, 63 percent had brain symptoms when patients were hospitalized, and 82 percent had neurological complications at any time during their illness.

The most common neurological complications were:

- Muscle aches (45 percent)

- Headaches (38 percent)

- Encephalopathy or global brain dysfunction (32 percent)

- Dizziness (30 percent)

- Altered sense of taste (16 percent)

- Anosmia or lack of smell (11 percent).

Most of these symptoms are relatively mild and would inconvenience but probably not majorly limit functional ability, Liotta explains.

Meanwhile, the side effect that keeps him up at night is encephalopathy, which can change behavior, mood, and cognitive ability. It's a broad term for any brain disease that alters brain function or structure.

"Encephalopathy is probably the most important of the neurologic manifestations because it impacts mortality and outcomes, and it was very common," Liotta says.

In contrast, strokes, movement disorders, motor and sensory deficits, ataxia (loss of full control of body movements), and seizures were uncommon (0.2 to 1.4 percent of patients).

"People can certainly have a very poor outcome if they have a big stroke as a chance event from Covid," Liotta says. "But it was so much less common, that its impact on the community we suspect is likely to be less than this global brain dysfunction, which, unfortunately, isn't that well-understood."

Liotta's study jibes with a study published in October in the journal Neurology. Those authors analyzed 4,491 hospitalized Covid-19 patients and found that 13.5 percent of patients received a neurologic diagnosis, most commonly encephalopathy, stroke, seizure, or brain injury due to lack of oxygen or blood supply.

These disorders put patients at a 38 percent increased risk of dying in the hospital, and a 28 percent reduced likelihood of being discharged to go home.

How long do symptoms last?

Although there are currently over 200 case reports and studies exploring how Covid-19 impacts the brain, health experts have far more questions than answers.

"I know, from personal experience, patients who've been in the ICU and encephalopathic and go back to work and their usual activities in the span of weeks to months," Liotta says.

"But there is definitely a substantial group of patients who are still dealing with some cognitive problems months to even a year out."

To pin down the exact prevalence of Covid-19 brain-related problems, researchers need to undertake large-scale, longitudinal studies that track a wide range of patients — in and outside the hospital— over time.

When asked about "neuro-Covid," Levine said, "I wish I had more concrete answers for you."

"I feel like we've just been hit by a tidal wave and we're all just kind of struggling to stay afloat. As scientists and clinicians, we're like, 'Wow, we really don't know what's going on,'" Levine says.

"We read papers every day, and there are different ideas, but at the moment, there are no solid answers."

How does Sars-CoV-2 attack the brain?

While scientists haven't pinned down exactly how Covid-19 harms the brain, they do have a few theories.

Evidence suggests coronavirus can be neuroinvasive, directly penetrating brain tissue. Researchers have detected its viral RNA in the cerebrospinal fluid and brain tissue of a small fraction of infected patients. However, this direct viral invasion appears to be exceedingly rare.

Many health experts, including Levine, speculate that some neurological complications may stem from the body's response to the virus, not the virus itself. This response could be very varied depending on people's genetic makeup, and their history of past infections or medical conditions, Levine adds.

That's because, in fighting Covid-19, the immune system can spiral out of control, creating an outsized inflammatory reaction called a cytokine storm. These storms can overburden the body, cause organ failure, put brain function in jeopardy, contribute to Guillain-Barre syndrome (where the immune system attacks your nerves), and even lead to death.

It's also possible, Liotta says, that some of the coronavirus' negative neural effects are linked to patients' treatment in the hospital.

While health care providers work to minimize harm and save lives in the hospital, their interventions can sometimes do lasting neurological and psychological damage in the process. That's because treatment can involve incubating or putting patients on ventilators, include strong sedatives, and lead to severely disrupted sleep. Patients report the lack of control and difficulty breathing can "feel like drowning," Levine says.

The hospital experience can cause post-traumatic stress disorder and lead to globalized inflammation and brain dysfunction, both Levine and Liotta note.

"Because of the trauma that people go through just from an ICU stay, or undergoing mechanical ventilation and experiencing delirium in the ICU or the hospital — those things themselves can lead to psychological trauma and neurocognitive deficits," Levine says.

Searching for answers — For now, the underlying mechanisms driving Covid-19's impacts on the brain are explained by theories, not robust proof. Meanwhile, when it comes to treating "neuro-Covid", options are currently limited and case-specific.

"Unfortunately, there's not like a pill or a medication that somebody could take to make this problem better," Liotta says, explaining the challenge of treating encephalopathy.

There are just so many potential causes for this, Levine says, and there aren't yet any definitive answers.

"Is it the virus itself that's remaining in the brain?" Levine asks.

"Is it your immune system at a hyper-vigilant state? Is there this chronic state of inflammation going on in the brain or systemically? Is it psychological? Is it just anxiety and you're not getting enough sleep, and then you start worrying about the brain fog, and then that causes more anxiety and even more difficulty sleeping?"

To really understand what's going on, Liotta and Levine stress the need for large, systematic studies. Until those results come in, understanding and treating Covid-19 patients' brain dysfunction will be a guessing game.

This article was originally published on