Clifford V. Johnson has the coolest job in physics. Here's how he got there.

A scientist with an IMDb page explains how to shape your early career.

The first text to appear on Clifford V. Johnson's personal website is the same verse that Bilbo Baggins sings as he leaves The Shire and sets out toward Rivendell. It's not an odd choice for a physicist who would go on to advise for movies like Avengers: Endgame.

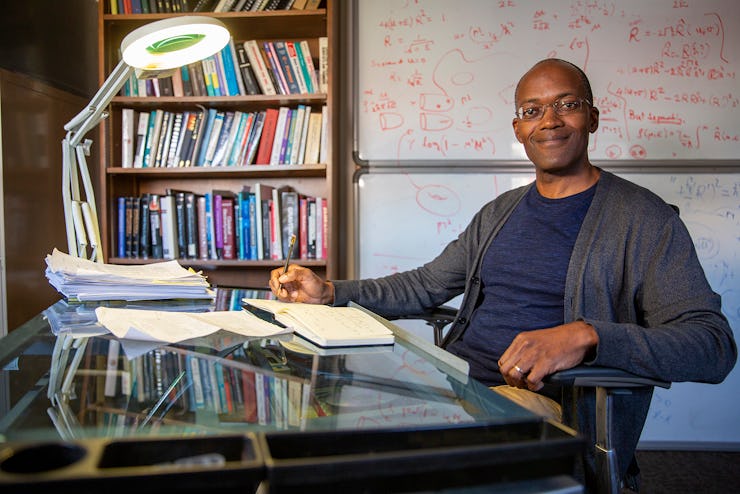

Johnson is a professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Southern California, where his work centers around describing the origins of the Universe. He's been awarded the National Science Foundation's CAREER Award – one of the organization's most prestigious awards for early-career faculty. He's also a recipient of the Institute of Physics' James Clerk Maxwell Medal and Prize, which is awarded for outstanding early career contributions to theoretical physics.

He's also the author of The Dialogues, the 2017 graphic novel about the science of the universe for non-experts. As Johnson told the Los Angeles Times, the novel is meant to be a modern-day Socratic dialogue — a question-and-answer conversation format that helps clarify logic and ideas. Ultimately, those conversations are a crash course in how to talk about science with the clarity of an expert but the tenor of a regular person. And talking about science has become just as much a defining pillar of Johnson's career as doing physics itself.

Not many theoretical physicists have IMDb pages, but Johnson is one of them. Thanks to Johnson, many of our most wild-ride sci-fi fantasies (Avengers: Endgame, Infinity War, Ms. Marvel, Star Trek: Discovery – the list goes on) have a real-life flavor. As IndieWire reported, it was thanks to Johnson that we know Thor's hammer was forged in the “heart of a dying star.” He also helped theorize potential time travel scenarios that became the central plot of Avengers: Endgame.

Like the Hobbit whose song is plastered to the top of his webpage, Johnson's career has followed a long and winding journey from London to the Caribbean, back to London, then to New Jersey, and finally to Los Angeles. Unlike Bilbo, Johnson has always known where he was headed.

Inverse spoke to Johnson on how he's battled preconceived notions about race and physics, the kind of advice you should be “happy to reject,” and why you shouldn't go ice skating before big exams.

In the Inverse original series ROOKIE YEAR, leaders in STEM, business, and the arts give us a crash course in early adulthood, breaking down the triumphs, stumbles, and lessons learned from their first year in the working world.

Clifford V. Johnson, a physicist at the University of Southern California.

When did you realize you were pursuing a career you loved? How did you come to that realization?

I was just sort of sure that I wanted to be a scientist and a physicist. My goal then was just to figure out how to do that, and how to get past all the obstacles. The normal ones everyone faces and all the others to do with, you know, how I look and who I am.

The main task was trying not to be knocked off track by all the things that can knock you off track. It's not usual that people with my ethnic background pursue this career as often as it would be, ideally. Putting it lightly, there were obstructions there.

My first job was when I was a postdoc. That was at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, which is one of those sort of Meccas for physics.

Do you remember your first day there? How did you feel when you walked in? How did you start to feel situated?

Especially because I was it was my first job at one of the top places in physics, there's always this feeling – it's a cliche – but there is imposter syndrome. You're just a little bit terrified that you maybe shouldn't be there. And, of course, if you're from an unusual demographic in that field, there's this extra feeling. In fact, there are attitudes around you that are also telling you: “You don't belong.”

A panel from Johnson's graphic novel 'The Dialogues'.

You have to fight against that, and it can be tough. I remember that feeling of “this is exciting,” [and] “do I really belong here?” Then, “I'm going to prove that I do belong here.”

You just do the best you can and focus on the main thing, which is just enjoying doing what you're doing and not worrying about what other people think.

In the montage of that first year on the job, what song would play in the background?

It's a song by Queen and it's called "Don't Stop Me Now." It goes back to a moment in my youth where everything was transitioning.

I was born in London; I lived there for a while. Then, my parents, who are from the Caribbean, took us all to the Caribbean for some years. Coming back 10 years later, I was coming back to this world that I vaguely remembered. I was coming back to this world to persevere. I was going back to the big city; I was going to do science. I was going to do all these amazing things.

On the plane, they had just a loop of music playing on these little plastic tubes that you stuck into your ears. The song that I kept getting excited for when it would come ‘round next was “Don't Stop Me Now.” It really embodied the moment of: “Ok, now it begins. Just get out of my way; I'm going to do this.”

Do you think it's important to have a mentor? If so, how did you get one?

When I was a graduate student, I had a graduate advisor. That's really, really huge and crucial. But I think you're probably asking about it at the job stage.

Mentors take different forms. That could be just someone who does the job that you do but has been doing it a bit longer and can give you a warning about the pitfalls or just show you how to do what you do better.

“Take your time changing lanes, don't swerve.”

I think you pick [career advice] up just collectively. It's good to have a community of people. No one's necessarily playing the role of advisor or mentor, but collectively everyone is kind of just contributing to that environment of passing on folklore about how to get by. It's stories about how “that person did this and they got hired” or “that person did this and they didn't get hired.”

Folklore in that sense is storytelling, gossip, all of those things. There's a huge component of that, and it's extremely valuable for helping you make your own path. I think some of that is mentorship, too.

Can you think of a moment in your early career where you had to innovate?

One of the things that I figured out I should do very early on is keep innovating – teaching myself new skills. And that means working in completely different areas in my field. I would essentially reinvent myself every now and again in terms of the kinds of physics problem that I was looking at.

That served two purposes. One was deliberate: I find it all interesting. It also means you get the opportunity to make people aware that you're there. You're kind of making a nuisance of yourself.

There are things, like, at a certain time of year when it's that round of applying for new jobs (everyone in my field does it around the same time), I would try to go out there and give talks in as many places as you can.

A lot of the innovation was about trying not to stand still – to keep moving and finding ways of making myself known.

Is that the sentiment behind some of the science communication work you do?

That's completely different. That isn't about me getting a job. That was about my thinking that science belongs to everybody. I do it because I think it's important to bring science into the general culture.

A trailer for Johnson's graphic novel, The Dialogues.

I think that the perception of who a scientist is: who the different kinds of scientists are, what they do and what it's like, is not so good. I think there's a huge barrier, especially when I started blogging back in the early 2000s.

I think it has changed positively a little bit, but there's still a long way to go.

What's an early career mistake you made and what did you learn from it?

I remember giving a spectacularly bad and misjudged talk. I was giving a departmental colloquium [a talk to a whole department] I think at the University of Maryland.

I had this great sort of metaphor for the kind of physics that I was giving the talk about. I completely overused the metaphor and completely lost the science inside the effort to try and push that metaphor. I just remembered sinking like a lead balloon in terms of how it went over to that audience.

In terms of career mistakes, I think that was probably one of not knowing your audience well enough when planning your presentation or big show.

So it wasn't super dramatic. I think giving a colloquium and misjudging your audience is, like, a really basic mistake that hopefully you do not make later on. But nevertheless, I do remember feeling bad about it for a long time.

How do you know it’s time to ask for your first raise, and do you have any advice for doing that?

I don’t really have a good answer for that one. I’ve never done that!

At junior levels, academia tends to have fairly standard scales and increments that people tend to adhere to. By the time you get to be very senior, you might negotiate, but it is usually at a change of job. There are usually standard annual raises based on performance, etc.

So asking for a raise is not, as far as I know, so common, and I’ve never actually done it in my life. Perhaps I should!

What advice would you give to someone who is realizing they're on a career path they don't want to be on?

Before changing lanes, first, have a long period of reflection as to why you think you no longer want to be in this area. It might not be to do with the career; it might be to do with recent events or something like that. Make sure you're not just impulsively giving up on something because you had a bad review or you gave a really terrible talk.

That might mean you take some time to figure out what your passions are really for. If you can, find something that aligns with your passion, but it doesn't have to be exactly the same thing.

If that feeling remains, be careful. Jobs are hard to come by. Find ways of planning your next move carefully. Being in a secure job gives you the baseline of security you need to then gradually begin to transition. Take your time changing lanes, don't swerve.

That's the way I would do it. But I'm a naturally cautious person. I was the kid who didn't go ice skating with all his friends because the exams were coming up and I didn't want to have anything happen that could mess up that important time for my career.

What's the best piece of professional advice you've ever received?

The safe thing for me to do would have been to take off back to the UK when I had finished my work at that first postdoc in Princeton. A major decision point was: Do I go back to the UK or do I try and make it here for longer? I took a leap of faith and stayed outside my comfort zone. I decided that I was going to stay out on the limb a bit longer.

It may well have been that someone suggested to me: “Hey, you know, get out of your comfort zone a little bit.”

Try and get out of your comfort zone. Otherwise, you won't grow. That is that is a piece of advice I do give to people. And if someone told me that, well, thank you.

What’s the worst piece of professional advice you’ve received?

I've been told many times that I'm probably not cut out for this, I should go do something else. I should emphasize that no person serving as a mentor of mine made such a suggestion. This came from others.

That piece of advice was something that I was always happy to reject. Actually, sometimes I was glad when people told me that because it made me go, I'm going to show you. And I did, and some of those people are no longer in the field.

And I am still here.

The interview above has been edited for clarity and brevity.