What are the physical signs of anxiety? Why your body’s cues may throw you off

How we feel about what is going on with our bodies is not always correct.

If you’ve ever taken a long breath while feeling anxious, then you’ve deployed one of the best coping strategies for managing your unease.

Breathing techniques, like box breathing and diaphragmatic breathing, are known to benefit mental health. The effect breath work has on one’s sense of well-being is to do with the relationship between the body and the brain. The body tends to interpret mental stress as if it is physical stress. For example, anxiety can trigger physical symptoms as it arises, like shortness of breath or sweaty palms. Over the longer term, generalized anxiety disorder is associated with symptoms like insomnia and stomach problems.

In turn, breathing helps regulate our mental state. Rapid breathing, like panting, can amplify anxiety while breathing slowly helps precipitate an anti-stress response.

Critically, how we feel about what is going on with our bodies is not always correct. Research suggests clinically anxious people are especially likely to misinterpret bodily signals when it comes to breathing. They may, for example, not notice changes in their breathing until they are short of breath. Once there, they might feel even more anxious.

Individual differences in how we perceive and interpret bodily signals may account for differences in behavior. You can train yourself to pay attention to these signals through actions like mindfulness, yoga, and — of course — breathing exercises. But learning why this mismatch occurs is also a critical step toward improving mental health overall.

Interoception: What the science says

Perceiving a bodily state typically associated with anxiety — such as shortness of breath — can result in feeling anxious, even if there is no anxiety trigger.

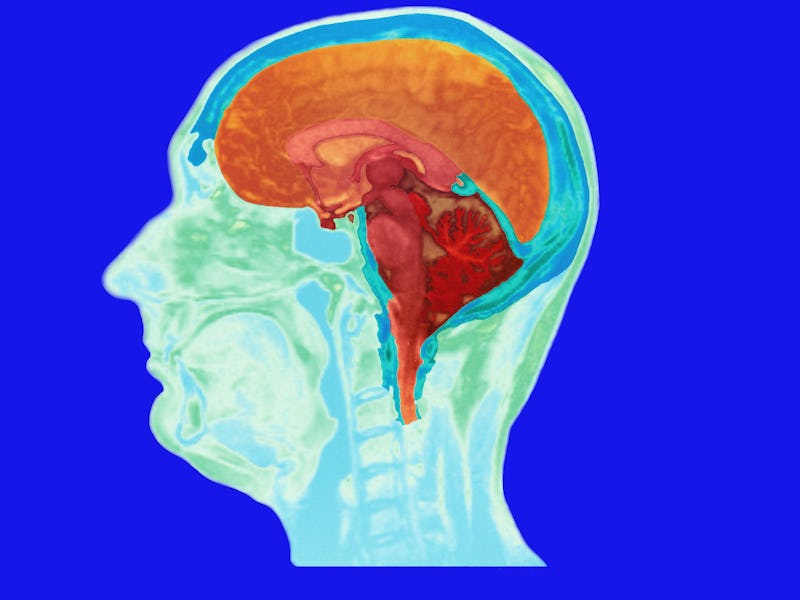

Exteroception is an academic word for how we sense and interpret our external environment — the stuff around us. We use sight, sound, taste, touch, and smell as clues. Interoception, by contrast, refers to our internal awareness. We use internal signals, like a heartbeat or an ache, to perceive and assess what is going on inside our bodies.

But here’s the catch: Our interoception doesn’t always capture our physical state. Several studies suggest some people with depression are less able to feel and evaluate their bodily signals. The same is true for groups of people with anxiety — there is evidence anxious people might incorrectly interpret these sensations and what they mean. This miscommunication between the brain and body may be a critical component of anxiety.

Olivia Harrison is a senior lecturer and the Rutherford Discovery Fellow at the University of Otago. She recently co-authored a paper examining interoception, breathing, and the link to anxiety. The analysis was published in the journal Neuron.

Harrison and her colleagues observed that perceiving a bodily state typically associated with anxiety — such as shortness of breath — can result in feeling anxious, even if there is no anxiety trigger. Furthermore, this study team found this “prediction error” is associated with specific patterns of brain activity in a region called the anterior insula, which is thought to be involved in assessing subjective feelings.

“They don’t tend to trust or feel safe in their bodies as much.”

Harrison tells me that it’s fair to say interoception can sometimes mislead us.

“We might have an ‘over-perception,’ where we feel threatened by what is going on in our body even though we might be safe,” she says. “Or we might have an ‘under-perception,’ where we don’t notice changes in our body early on until they appear to come out of the blue and maybe give us a fright.”

Individuals with greater anxiety levels are more likely to associate their body signals with negative emotions, the study finds.

“They don’t tend to trust or feel safe in their bodies as much,” Harrison explains.

Harrison theorizes that mismatches in interoception may stem from several causes, which, in turn, may differ across individuals and conditions.

Harrison and her team are currently conducting studies evaluating interventions like medication and exercise to treat anxiety and how these might affect interoception.

Shortness of breath and anxiety

Rather than thinking of anxiety and breathlessness as an A-to-B situation — where one event leads to another — it can more helpful to think of the process as a cycle. Feeling breathless, breathing quickly, feeling anxious, and having worrying thoughts all generate a negative feedback loop.

When you feel like you’re in danger, but you’re actually safe, you might feel anxious regardless. The experience can cause the brain to signal to the autonomic nervous system, divided into the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. The latter is associated with resting and disgesting, while the former is our so-called fight-or-flight response. It prepares the body for emergencies and sends it on high alert when we feel stress and anxiety.

This reaction often manifests in physical changes, like increased heart rate, changes in blood flow, and altered pace and depth of breathing. The positive side to this is that your muscle tissue is flooded with extra oxygen, which helps the body get ready to take action — or run away. But it also can cause a feeling of breathlessness and tightness in your chest.

This feeling is good if a bear is chasing after you. It’s less helpful if the bear isn’t there.

This article was originally published on