Look! Astronomers Have Never Seen A Pair Of Supermassive Black Holes So Close Together

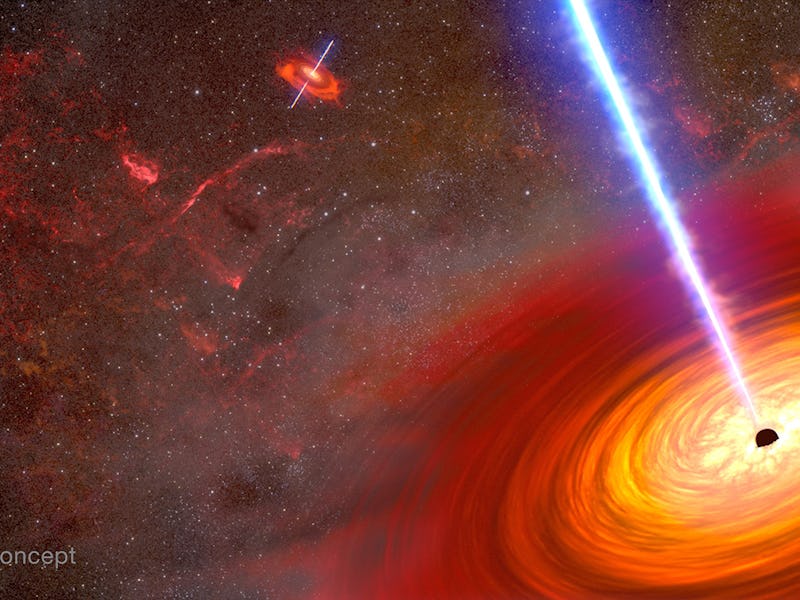

Telescopes captured two supermassive black holes falling toward each other.

Astronomers recently captured two supermassive black holes in a hundred-million-year death spiral toward an epic collision.

The two black holes are near the center of a galaxy shaped by the aftermath of a recent merger between two smaller galaxies, and their fate offers a preview of what might happen to Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the heart of our own galaxy, in a few million years. Harvard University astrophysicist Anna Falcão and her colleagues published their work in The Astrophysical Journal.

This Hubble Space Telescope image shows the galaxy MCG-03-34-64, with the pair of glowing supermassive black holes at its center.

Cosmic Leviathans on a Collision Course

Astronomers recently peered deep into the heart of a galaxy 800 million light years away with the Hubble Space Telescope, the Chandra X-ray Observatory (which orbits roughly 70,000 miles above Earth, 200 times farther away than Hubble), and the Very Large Array (yes, that’s it’s real name), a radio telescope on the ground in New Mexico. They found a pair of objects, both blazing brightly with visible light and X-rays while blasting powerful radio waves out into space.

“We put these pieces together and concluded that we were likely looking at two closely-spaced supermassive black holes,” says Falcão in a recent statement.

The pair of supermassive black holes glow so brightly because they’re actively “feeding” on the gas around them. As gas falls, faster and faster, toward the ravenous heart of a black hole, gas molecules collide and release energy: bright light, x-rays, and radio waves. That rushing swirl of material is what the Event Horizon Telescope imaged (and can now image in color), and it’s what revealed this pair of leviathans to Falcão and her colleagues.

At some point in the past, two galaxies collided and merged — the same fate that awaits our Milky Way galaxy and nearby (too nearby for comfort) Andromeda Galaxy in about 4.5 billion years, but don’t worry; the Sun will have swallowed us all by then, anyway. The result is a galaxy called MCG-03-34-64, a name which really rolls off the tongue like sheer poetry. When galaxies merge, the supermassive black holes at their centers usually also merge — eventually. (Sometimes one of them gets booted out into space, because these collisions are violent and involve forces on a scale that’s hard for human minds to conceive). But for millions or sometimes billions of years, they can be trapped in a slowly-decaying orbit around a shared center of gravity. Falcão and her colleagues estimate that these two black holes will finally fall into each other in around 100 million years, and when they do, they’ll send shock waves through the very fabric of spacetime.

Astrophysicists have never recorded the gravitational waves from such a gargantuan collision. The biggest gravitational wave observatories on Earth, like the Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO), span about 2.5 miles — about the right distance to catch the relatively short ripples from collisions between stellar-mass black holes (the remains of stars less than 100 times the mass of our Sun) or neutron stars. A merger between two objects like the black hole at the heart of our galaxy, which carries more than 4.3 million times the mass of our Sun, would produce waves too large for LIGO to detect.

To detect gravitational waves that big, with wavelengths that long, astronomers plan to build a version of LIGO, called the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), to sit in space and whose detectors will be spread millions of miles apart in orbit. If everything goes according to plan, LISA should launch sometime in the next decade. And who knows what instruments astronomers will have available when the supermassive black holes in MCG-03-34-64 finally collide in 100 million years.