NASA wants to know how loud a sonic boom can be without scaring the hell out of you

The newest X-plane will help them find out

xOn October 14, 1947, Chuck Yeager's X-1 was the first human-piloted aircraft to break the sound barrier in level flight. That was just 44 years after the Wright Brothers first took flight in Kitty Hawk, which is an astonishingly short period of time.

It's been almost 74 years since Yeager's flight, and though plenty of aircraft can fly faster than the speed of sound today, vanishingly few people have experienced it. Aside from military pilots and folks who were lucky enough to be a passenger on the Concorde — which itself retired almost 18 years ago — there's no opportunity for anyone to fly that fast.

But thanks to a brand new X-Plane (the government term for an experimental plane), that may be changing.

The X-59 Quiet SuperSonic Technology research aircraft is a single-seater with a unique design that'll reduce the boom down to a thump. In fact, NASA is even calling it a "Low-Boom Flight Demonstration Mission." But this plane isn't pushing the ragged edge of air travel like Yeager's X-1. Instead, it’s more about what's happening on the ground than what's going on at 55,000-feet.

About supersonic flight

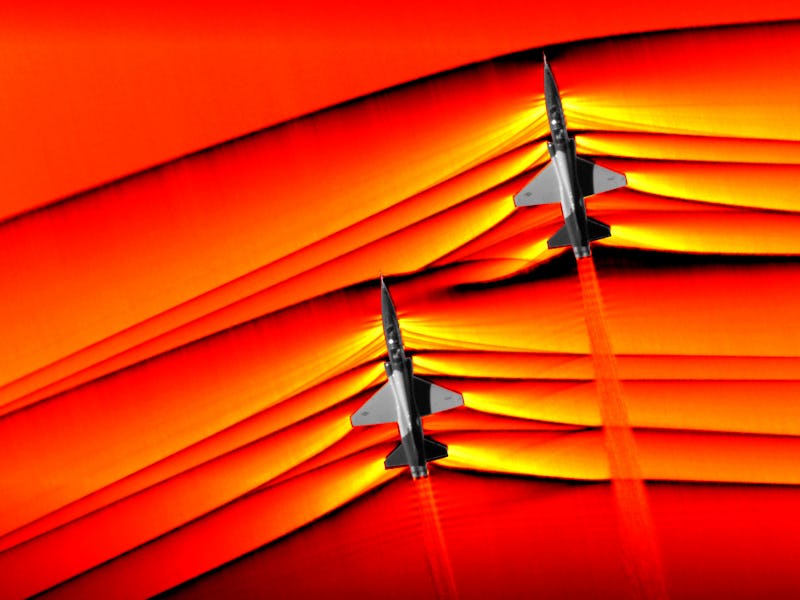

The problem with supersonic flight is that a plane traveling faster than sound creates a shockwave that can cause disturbing effects on the ground, even if the plane is flying along at 45,000 feet or higher. The supersonic boom can wake people up, crack windows, and generally scare the hell out of everyone.

Bob van der Linden has one of the coolest job titles around: Curator of Air Transportation and Special Purpose Aircraft in the Aeronautics Department of the Smithsonian. He reiterates that the big problem with breaking the sound barrier is ... well, the sonic boom.

"If you can reduce the boom to the point where nobody cares, you've just doubled or tripled your possible routes around the world," explained van der Linden in an interview with Inverse. "You can fly transcontinental across the US, Asia, Europe, or anywhere. Right now you're totally prohibited from it."

In 2010, a pair of Oregon Air National Guard F-15s ripped up from Portland up towards Seattle to intercept a plane that had flown into the protective cordon surrounding Air Force One. The twin sonic booms caused by the planes caused Seattle-area 911 centers to be swamped with calls about the odd phenomenon.

Even still, the planes arrived too late to intercept the seaplane, which had landed on a lake by the time they arrived (and the pilot was met by some probably-less-than-friendly Secret Service agents). But it illustrates why supersonic flight is basically banned across all populated areas around the world.

The Air France Concorde F-BVFA, making its last flight, arrives from Paris at Washington Dulles International Airport.

The Concorde, perhaps the most famous faster-than-sound jet around, was de facto restricted to New York-to-London and New York-to-Paris flights. Those were the only city pairs to even come close to filling the plane's exorbitantly expensive seats, but also for more practical purposes: all those cities are located close to their country’s coasts, with only ocean in between.

Concorde could take off from JFK or Heathrow or de Gaulle and be over water in a matter of minutes, and proceed to get cracking above 1,000 mph soon after. But what if we could get rid of that sonic boom, or at least muffle it enough so it wouldn't scare the stuffing out of everyone in the general vicinity?

The cockpit of Concorde.

There are a whole host of companies developing jets that smooth the surrounding air in such a way that the faster-than-sound shockwave is mostly dissipated around the aircraft, causing a gentle and altogether more pleasing "whump" on the ground rather than a massive "whack" that sounds like lightning struck two feet behind you.

But the aerospace tech to make a quieter supersonic is only half the problem. The other half is regulatory, and that's what NASA's latest X-Plane is aiming to figure out.

"If you can reduce it to a little boom-boom," says van der Linden, "nobody will care. It'll just be more routine background noise in a city. No windows will be broken and no one will complain to the local authorities or their Congressmen."

A rendering of the X-59 taking off.

How does the X-59 quiet sonic booms?

While NASA and the aviation industry seem to have figured out how to reduce the sonic boom, they have yet to determine by how much they need to reduce it to keep folks on the ground from being freaked out. That's what the X-59 is all about.

It's focused on "community testing", which is a nice way of saying they're going to fly the X-59 around breaking the sound barrier and seeing how much it annoys people. Gautam Shah is the X-59 Community Testing Subproject Manager at NASA.

"The community tests give us the opportunity to gauge public response to a lower level of sound," Shah tells Inverse. "Now that we have low boom aircraft, we can make low sonic thumps. But until we have that aircraft, we have no way to know the range of potential acceptability."

The X-59 flight simulator.

In other words, we don't know how loud — or actually, how quiet — the sonic thump needs to be in order to not be annoying. NASA plans to survey community members in four to six metropolitan areas around the country, as well as placing as many as 150 microphones across a 50-mile wide swath of each city to confirm their noise level predictions.

"We'll survey the members of the community to get their response," Shah says. "Did you notice it? How much did it influence you or affect you? And we can try to gauge it. If you lower that sound, at what point is it no longer noticeable or at least acceptable?"

The X-59 has been designed for a perceived level of loudness of around 75 decibels, which is around the level of a vacuum cleaner — but it's what's called an impulsive sound, or a short and potentially more startling noise akin to a car door slamming. People are used to the drone of a jet airplane flying overhead, but it starts quiet and then builds up rather than being sudden and surprising like a thunderclap.

So the X-59 project is going to gather data on public perception of loudness and to determine if there's a noise standard that can be applied for supersonic flight over land.

A rendering of the X-59 in flight.

When is the X-59 first flight?

The mission is for the X-59 to do two supersonic passes per flight. They'll only be five-minute stints above Mach 1 — probably around Mach 1.4, NASA says — but at those speeds, the plane will cover 50 miles easily. Then it'll slow down and loiter for 20 minutes and then make another pass. The plan is to do two to three flights a day for a month or two in each area.

"It's an aircraft built to do one thing," Lori Ozoroski, commercial supersonic technology project manager at NASA, tells Inverse. "That's to be able to generate the sonic boom thump that we need to generate in order to gather the data for changing the regulations to allow supersonic flight over land. It’s all about the sonic boom."

"It's all about the sonic boom."

But don't expect to be seeing the X-59 to be cruising overhead any time soon; this is a slow, deliberate process. The NASA team, along with industry partners including the famed Lockheed Martin Skunk Works that is building the craft, hopes to make the first flight in June 2022 after ground testing later this year.

The first community testing likely won't occur until 2024, starting at the NASA Armstrong facility at Edwards Air Force Base in California. Testing in other areas will then run through 2026.

"They're trying to solve something that's been a problem for 75 years. If this works, it may make the return of supersonic transport possible," says van der Linden. "Right now, it's just not."

If you liked this, you’ll love my weekly car review newsletter PRNDL. Click here to subscribe for free on Substack. I’ll even answer your new car questions!

This article was originally published on