Experts say deepfakes could swing the 2020 election

Don't trust your senses.

It’s 2:00 pm on Monday, November 2nd, the day before the 2020 election. A video of the Democratic candidate saying something unforgivable goes viral on social media. Donald Trump shares the video and harshly condemns his opponent. Cable news outlets feel compelled to discuss the video due to its controversial nature. The next day, while votes are already being cast across the nation, news agencies are able to confirm that the video was a deepfake, but it’s too late. Donald Trump is reelected.

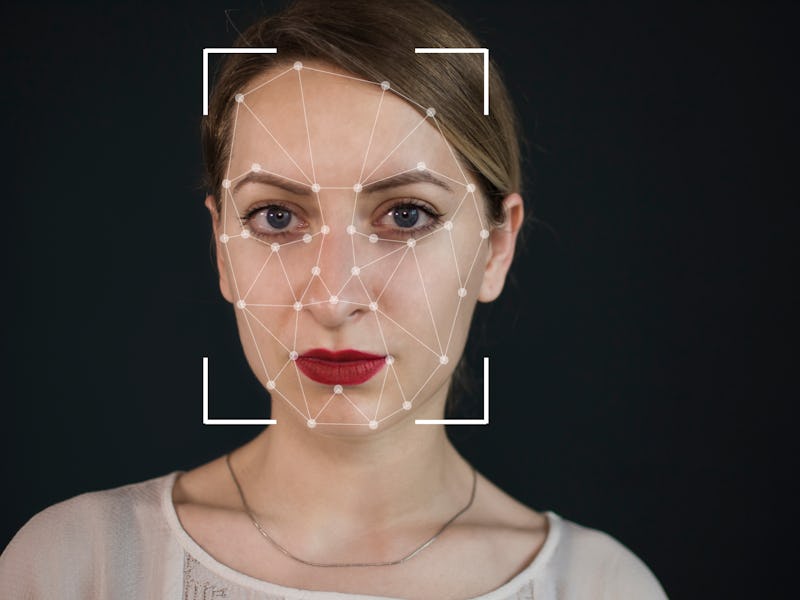

I’m not going to tell you this is something that will happen, but this scenario — a deepfake disaster — is within the realm of possibility. Deepfakes are fraudulent videos created using artificial intelligence and machine learning, which can be used to make a notable figure say and do pretty much whatever you want. There are also deepfakes that have been made that are solely audio. They are created by training A.I. to mimic someone’s voice and facial expressions by having it analyze samples of existing audio and video that feature that person.

This technology has been developing for years, and it was widely discussed when Jordan Peele released a deepfake of former President Obama last year to warn us of what could be done with this technology. As things stand, it’s not easy or cheap to produce a convincing deepfake, but this technology is becoming increasingly accessible. In the not-too-distant future, most people with technical expertise will be able to produce quality deepfakes.

Previously, Inverse has discussed deepfakes with the founders of an A.I. startup called Dessa that had just released a deepfake of Joe Rogan. Ragavan Thurairatnam, co-founder and chief of machine learning at Dessa, told us he’s confident deepfakes will have an impact on the 2020 election.

“There’s a very high likelihood that deepfake technology — video or voice — will be used as we get closer to the U.S. election—to actually compromise the election,” Thurairatnam said.

Thurairatnam isn’t alone in feeling this way. John Villasenor, a professor at UCLA who focuses on artificial intelligence and cybersecurity, told CNBC in October that deepfakes will become a “powerful tool” for influencing elections. Rep. Yvette D. Clarke (D-NY) wrote an opinion piece for Quartz in July that claimed deepfakes “will influence the 2020 election.”

Presidential elections are known for what is called the “October surprise.” That’s when harmful information about a candidate is deliberately released right before the election to swing the election in their opponent’s favor. Researchers are currently developing methods, often utilizing A.I. and machine learning, for detecting deepfakes, but the technology for creating convincing deepfakes is advancing simultaneously. This means it could take quite some time to verify if a video is a deepfake during the 2020 election, and if there isn’t much time left before people start voting, the news that the video was a fake might come too late.

Brooke Binkowski, the former managing editor of Snopes who is now the managing editor of the fact-checking website Truth or Fiction, is an expert on disinformation. She tells Inverse deepfakes will “almost certainly” be used to influence elections looking forward. Binkowski says the media has not done a great job at stopping the spread of disinformation over the past four years, and it’s likely some news outlets would show a deepfake before verifying if the video is real or not just because it’s getting a lot of attention.

“Reporters have got to learn to start covering obvious lies and obvious fakes critically, instead of the ‘both sides’ bullshit that’s infected the journalistic world,” Binkowski says. She says “truth and reality” are not up for debate, but reporters often act like they are in an attempt to appear unbiased.

“It’s corrosive and has worked so far — let’s make sure it stops working,” Binkowski says.

Even crudely edited videos and satirical videos have been spread far and wide recently before it was eventually confirmed that they were fraudulent.

Last year, a doctored video of CNN reporter Jim Acosta allegedly being aggressive with a White House aide that seems to have originated with the far-right conspiracy website Infowars was used by the White House to defend the Trump administration revoking his security credentials. Binkowski says people argued over if the video was legitimate for days. More recently, a satirical video produced by people from the Upright Citizens Brigade comedy group featured fake supporters of the presidential candidate Michael Bloomberg doing a ridiculous dance to Maroon 5’s “Moves Like Jagger.” The hashtag #MovesLikeBloomberg went viral, and the video received millions of views after being shared by political figures and even New York Times White House correspondent Maggie Haberman. The veracity of that video was still being debated two days after it went viral. A video of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi that was essentially just slowed to make her appear drunk was also heavily debated this year after it went viral. The list goes on.

If we are this easily tricked when counterfeit media should be quite easy to spot, are we truly prepared for a time when it’s going to become significantly more difficult to identify a fake? We can develop tools to detect deepfakes, but that doesn’t mean deepfakes won’t have a major impact at certain times when the people creating these videos are one step ahead of the people developing technology to detect them.

Tim Hwang, a well-known A.I. expert, tells Inverse that right now those who wish to tear down a candidate using fraudulent videos will still mostly be using cheaper, easier methods for altering existing videos. He said it still takes a pretty sophisticated operation to produce a believable deepfake.

“To the extent that we do see something like that, it really will be the act of some state actor or something like that—someone with the resources to invest in this sort of thing,” Hwang says. “The techniques are still kind of difficult for less sophisticated actors to be able to use effectively.”

That said, a deepfake might not need to be very good to be convincing. Hwang notes that, oftentimes, the videos that are most convincing and spread the farthest are the ones that aren’t high in quality.

“What actually seems to be more convincing to people is a shaky cellphone video or something that looks like it was kind of surreptitiously taken,” Hwang says. “I think deepfakes will become a factor but maybe not in the way we envision, which is these crystal clear videos depicting people that really change the conversation.”

Michael Horowitz, a professor of political science at the University of Pennsylvania, tells Inverse that he also thinks this kind of video will come from a “nation-state,” if it appears. Horowitz doesn’t think a deepfake will swing the 2020 election, but he says one problem we often face in the media is that even when you verify something was fake, people see the fake information more than the reports that it was fake.

“This could be a story where the error gets cited more than the correction. That, I guess, would be the concern,” Horowitz says. “At the end of the day, if you’re worried about this, what you’re really worried about is people. It’s about accepting information at face value due to confirmation bias and not using critical thinking.”

So what can be done? How do we avoid this problem? There’s no silver bullet, but everyone we spoke with agreed that we need to keep developing technology that can detect these deepfakes, that people need to be educated on what a deepfake is and that society needs to reconsider how it approaches video evidence.

“This is a powerful role that journalists have to play. There is a need for people who are specialized in sussing this stuff out,” Hwang says. “Sometimes it will take special expertise to figure out.”

Journalists need to be vigilant in looking for deepfakes and helping inform the public when a video is a deepfake, and the people developing technology to detect deepfakes need to be just as vigilant because bad actors will always be working to evade detection. As a society, we also need to simply improve our media literacy and think more critically when we evaluate new information.

We all saw how ill-prepared we were to combat disinformation campaigns during the 2016 election. We haven’t gotten much better at it, and technology is advancing that will create even more disinformation. Looking at his track record, there’s little doubt Trump would enthusiastically share a deepfake that could harm his opponent. The threat is real, and it’s fast approaching. If we don’t prepare for the worst-case scenario, then we’re inviting it.