Bird-like drones could be the flappy future of flight

A new drone design based on birds will allow for versatility unseen in current models.

Once an aerial equivalent of the Wild West, the world of drones has by and large become settled in both their design and varied uses: four small rotors forming at the center, taking the shape of a quadcopter. But an international team’s new drone could challenge the quadcopter’s dominance: the ornithopter.

The new design, which is detailed in a study published Wednesday the journal Science Robotics, gets its name from the Greek ornitho, which means birds.

That’s because this drone flaps its wings.

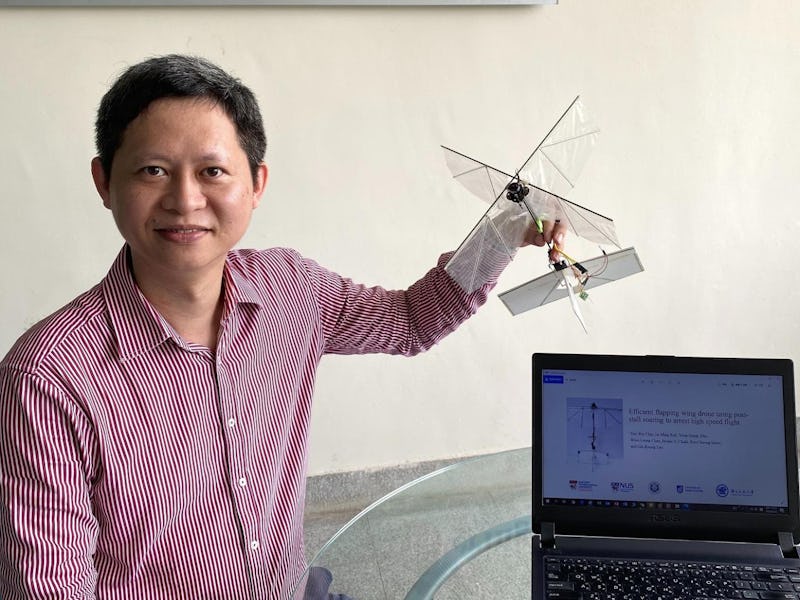

The new drone, same as the old drone — There have been other ornithopters before. The earliest efforts in human flight, from Abbas Ibn Firnas in the 9th century to Leonardo da Vinci in the 14th, began attempting to replicate birds. This new drone, which weighs in at 0.92 ounces (26 grams) — as light as two tablespoons of flour — follows in their tradition, and offers abilities that a traditional quadcopter can’t, says National University of Singapore research scientist and lead author Dr. Yao-Wei Chin.

"Unlike common quadcopters that are quite intrusive and not very agile, biologically-inspired drones could be used very successfully in a range of environments," Dr. Chin says in a press statement.

"Quadrotors are a little bit mundane now"

Javaan Chahl, University of South Australia aerospace engineering professor, goes one step further in an email to Inverse, saying that “quadrotors are a little bit mundane now,” a reference to the rotors spinning on each leg of a quadcopter.

"Anything very close to people is possible with these drones because their wings can be designed to be harmless."

New design, new uses — “The low speed of the wings compared to rotors makes them safer and the downwash is slower meaning it will cause less damage and disruption. There are many applications in surveillance, but we enjoy thinking outside of that area. Pollination of plants in greenhouses where insects are difficult to maintain is one idea we have,” he says.

“Anything very close to people is possible with these drones because their wings can be designed to be harmless. We could also use these types of drones for inspection close to delicate machinery, painted surfaces, glass and so on. One idea is for inspection of aircraft and chasing birds away from airports. This type of drone could one day be an autonomous companion and assistant to a person since it can be quieter, safer and requires charging less often.”

Chahl also says there’s potential in their new design for one of the quadcopter’s most popular uses: toys to fool around with at a park or the beach. While the technology still has to be developed further, “the combination of airplane and helicopter behavior of these drones would make them a much more versatile and interesting toy,” he speculates.

It wasn’t just any bird that inspired the team, Chal says. They were particularly inspired by the common swift, which the Audubon Society calls an “aerialist” for its tremendous flying ability. “We were inspired by its speed and agility, especially the way it can transition from fast forward flight to almost stationary in the blink of an eye as it lands in its nest,” he tells Inverse.

A close up of the new drone design, with each element broken down by weight. The entire drone weighs the equivalent of two tablespoons of flour.

This is real life — Animals are major sources of inspiration for robots, from dogs to cuttlefish. Chin, Chahl, and the rest of their team hope that their flapping drone can stand out due to its biological accuracy. "Many of the flapping wing drone projects in the world are inspired by birds and insects, but we are trying very hard to get even closer to the biology in future. There are many design principles of biological flight that seem to be very important, but that have never been in a robot,” Chahl tells Inverse.

They still have a long way to go to truly match the speed and power of a swift, Dr. Chin confirms in the press statement.

"Although ornithopters are the closest to biological flight with their flapping wing propulsion, birds and insects have multiple sets of muscles which enable them to fly incredibly fast, fold their wings, twist, open feather slots and save energy. Their wing agility allows them to turn their body in mid-air while still flapping at different speeds and angles.

At most, I would say we are replicating 10 percent of biological flight.”

The Inverse Analysis — There's a long way to go until these drones can master the abilities of the swift—10 percent is a long way from the full abilities of these birds. Yet it's also further than zero percent, and this prototype offers a number of exciting possibilities. The noise of drones is one of the most common complaints about the robots, and any drone that can reduce that noise would be welcome in the consumer market. If ornithopters could get strong enough to carry cameras, they could give quadcopters a serious run for their money.

Abstract: The identification and solution of a major efficiency loss in small flapping wing drones lead to more agile aerobatic maneuvers.

This article was originally published on