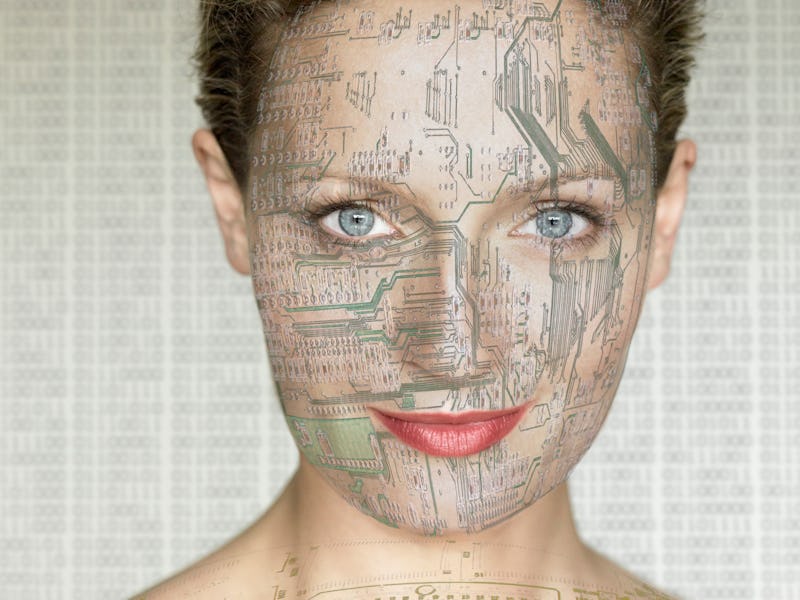

Scientists want to give you a bionic skin to save your life

A team of engineers has developed a super flexible, chip-free sensor that could revolutionize the medical industry — and even amp up our gaming experience.

From anti-infidelity rings to masks that change color with your emotions, wearable technology seems to have creeped into nearly every aspect of daily life. These rapidly developing sensors can serve as valuable tools for athletes, futuristic fashionistas, and even military personnel due to the massive amounts of helpful data they can amass.

But most wearable devices use circuit chips to record such information, making them relatively bulky and energy-intensive. What’s more, chips are in short supply, so these devices tend to be expensive. But new research may point to a cheaper, lighter solution.

A team of engineers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has developed a pliable electronic “skin” capable of collecting data on a wide range of health indicators, including heart rate, stress hormones, and the sodium ion concentrations in sweat. The sensor is super flexible and about as thick as a piece of scotch tape. Best of all, it can monitor all those metrics chip-free. The proof-of-concept paper was recently published in the journal Science.

“Chip-free sensors could have advantages in the aspects of low power consumption, high flexibility, and stretchability for better skin conformity,” Wei Gao, an applied engineer at the California Institute of Technology who was not involved in the new research, tells Inverse.

But how can a device monitor our vitals without any wires or chips? The secret lies in the material’s special properties.

This new wearable electronic “skin” is designed to send health indicators like glucose concentrations, blood pressure, heart rate, and activity levels to a smartphone. Unlike current wearables, it doesn’t require Bluetooth chips, so it could be much lighter and far more accurate.

What’s new — The MIT team's e-skin is made from gallium nitride, a material that generates its own electricity in response to mechanical stimulation, including moving one’s muscles. Once active, it collects data by selectively allowing sodium ions and other molecules from the wearer’s sweat to spread across its surface. Then, it sends that information to a nearby computer, no wires needed.

While a wearable’s computing usually goes down inside chip-based sensors, this new device leaves it to external computers. This makes the device much lighter and more energy efficient, says Jun Min Suh, a mechanical engineer at MIT who co-authored the new study.

Because e-skin sensors cover more surface area than chip-based ones and adhere directly to the user’s skin like a smart band-aid, the researchers also think it will be more accurate than most wearables. “Our device thickness is like, twenty or thirty micrometers,” said Suh, “It’s really very thin.”

That thinness has the added advantage of making the sensor more comfortable — and, because it lacks a chip processor, it never needs to be charged, meaning that the folks who use it are likely to wear it longer than today’s devices.

Studies have found that popular consumer-oriented wearables like the Apple Watch don’t deliver highly accurate data, but more precise devices are now in the works.

Here’s the background — Scientists first developed wearable sensors in the 1980s, but they didn’t really take off until the mid-2010s with the debut of popular fitness trackers like Fitbit and Apple Watch. But these waterproof plastic devices aren’t designed to analyze sweat; instead, they track metrics like heart rate, blood pressure, step count, and sleep. These gadgets aren’t considered highly accurate, and their usefulness varies based on specific metrics.

Plus, chip-based devices face a major hurdle: the global chip shortage. Since 2020, a perfect storm of factors, including the Covid-19 pandemic, supply chain instability, and flooding around the world, has led to a deficit of silicon chips around the world. While the automotive and computer industries have suffered the most, the wearable market hasn’t exactly escaped unscathed.

That’s why much of the research into chip-less sensors aims to circumvent future chip shortages — by reducing demand for them in the first place.

Why it matters — If they’re ultimately successful, paper-thin wearable devices like e-skin have huge potential in the medical world. For example, they can be tuned to monitor glucose levels in patients with diabetes or hypoglycemia, alerting them before they even experience symptoms of a blood sugar spike. Or, by keeping tabs on sodium levels in sweat, they can warn wearers of dangerous dehydration during hot summer months (a global issue that’s only expected to worsen due to climate change).

Many health-oriented wearables use circuit chips to record information, making them relatively bulky and energy-intensive. But this new technology could circumvent the need for chips and result in more flexible, lighter devices.

Beyond practical applications, the technology could even heighten your gaming experience. Suh and his co-authors hope that their e-skin could make its way into virtual reality games by monitoring levels of a stress hormone called cortisol, to which the game could be programmed to respond by increasing or decreasing difficulty. “This is a highly impressive work,” Gao says.

What’s next — E-skin isn’t quite ready for prime time. For one, the MIT team would like to improve the device’s range so that it can transmit data even when the wearer has roamed far from their computer.

“At the moment, the wireless communication is relatively short,” said Suh. “We want to expand our communication length to make it more practical.” They also hope to expand their biomarker library to recognize a larger array of molecules, including neurotransmitters.

Until then, we’ll have to be content with our imprecise smartwatches.