Microplastics Can Cross the Blood-Brain Barrier, A New Study Suggests — Here’s Why That Matters

Plastic levels in the brain were much higher than in organs surveyed.

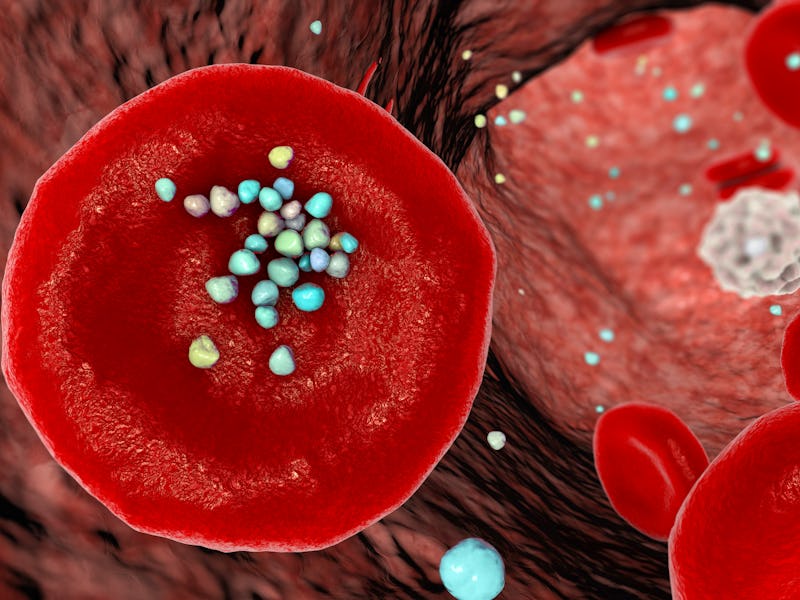

It feels like every few months, microplastics are cropping up someplace else they don’t belong: testicles, placentas, carotid artery plaque, lungs. These infinitesimally small plastic particles, which are smaller than 5 millimeters across, have most recently been detected in brains, according to a new study.

A preprint study — which is a scientific study that has not yet been reviewed by other scientists for publication in a journal — was posted online in May by the National Institutes of Health looking at the amount of microplastics in human brain samples from autopsies. The study found that brains had higher concentrations of microplastics than other organs, and that these autopsy samples also had higher concentrations of microplastics than autopsy samples from a 2016 study. Though this paper is still under review to ensure the methods and findings are trustworthy, the key results of the study exemplify yet another vital organ affected by microplastics.

For the study, the authors examined livers, kidneys, and brains from autopsied cadavers. They found that concentrations of microplastics in the brain samples they examined “ranged from 7 to 30 times the concentrations seen in livers or kidneys.” They also found that brain samples collected and analyzed in 2024 contained significantly higher concentrations of microplastic, with over 3,000 micrograms per gram of human tissue in 2016 and over 4,800 micrograms per gram in 2024. Some samples ranged as high as more than 8,800 micrograms of plastic per gram of brain tissue.

We don’t know yet what effects, if any, microplastics could have on the brain, but this study does confirm that these bits of plastic can cross the blood-brain barrier, which is the protective membrane that helps regulate what molecules enter the brain from circulating blood.

“Based on our observations, we think the brain is pulling in the very smallest nanostructures, like 100 to 200 nanometers in length, whereas some of the larger particles that are a micrometer to five micrometers go into the liver and kidneys,” lead author of the study Matthew Campen, a toxicologist and professor of pharmaceutical sciences at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, told CNN.

While it seems like microplastics are omnipresent in today’s society, figuring out how to affect our health is key.