Another Person With HIV Was Cured — Here's How The Treatment Works

A bone marrow transplant isn't an option for everyone with HIV.

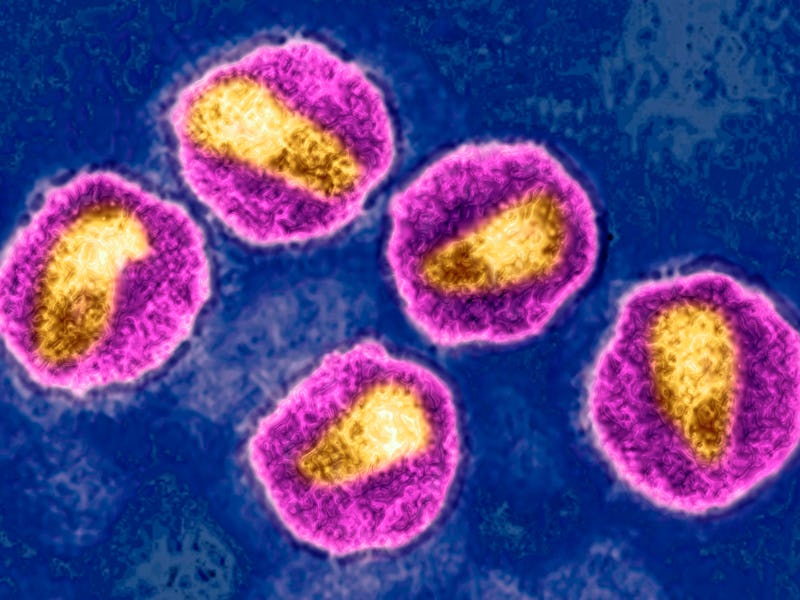

Since it first captured headlines in the 1980s, the human immunodeficiency virus, better known as HIV, has been a tough nut to crack. It’s not for a lack of trying, however. Science has come a long way in parsing out the virus’ operating manual and developing drugs, called antiretrovirals, that suppress or prevent it from replicating. But because of some nasty tricks up its sleeve, fully eradicating HIV has been damn near impossible.

That was until around 2008 when Timothy Ray Brown, an American living in Berlin, Germany, became the first person cured of HIV after receiving a bone marrow transplant he underwent to treat leukemia.

Brown’s success spurred numerous efforts to duplicate what his doctors did, but, so far, there have been only a handful of successful cases. The latest patient to be cured is a 53-year-old man, dubbed the “Düsseldorf patient”, who received a bone marrow transplant, much like Brown, to treat his leukemia. This individual underwent the procedure back in 2013 and remained on antiretroviral therapy until 2019, when he was declared as showing no functional signs of HIV, according to a study published Monday in the journal Nature Medicine.

This sort of cutting-edge treatment piggybacking off of current cancer therapies could “inform future strategies for achieving long-term remission of HIV-1,” the researchers of the new study write. However, there are some caveats to consider, such as risks associated with bone marrow transplants and that it’s not a likely treatment for all HIV patients, which number 38 million worldwide in 2021. Here’s what you need to know.

What does HIV do to our immune systems?

The primary target of HIV is the immune system. Once it enters the body through contact with certain bodily fluids of an infected person (usually blood, semen, vaginal fluids, and breast milk), it latches onto and enters a white blood cell called a T helper cell that plays a critical role in the immune system’s ability to clear an infection.

Inside the T helper cell, HIV releases its genetic material, integrating it into the cell’s genome using its in-house DNA Xerox machine. Safely ensconced in its host, the virus pretty much stays put and uses the cell to make more viruses, which go on to infect and eventually destroy other T helper cells.

This overboard parasitic relationship severely weakens and damages the immune system, leaving an individual vulnerable to all sorts of infections and even cancer. Over time, when left untreated, an HIV infection leads to a condition called acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (or AIDS).

The virus lying in wait inside its cellular sanctuaries and hobbling immune defenses are some of the reasons why HIV is so hard to treat (and why we don’t have a vaccine yet). Another reason is HIV is very prone to mutation. A consequence of this rapid mutation is that the virus can develop drug resistance, which is why antiretrovirals are given in combinations that target different stages of viral replication.

How does the bone marrow transplant work?

Essentially, a bone marrow transplant is a stem cell transplant. HIV-susceptible stem cells, which are the body’s raw cellular materials and give rise to immune cells, are swapped out for donor stem cells that are resistant to the virus because of a special mutation. Called CCR-delta 32, this mutation was initially discovered in 1996 by virologists in a man named Steve Crohn, who appeared to be largely immune to HIV.

CCR-delta 32 is a gene that encodes a protein on a T helper cell, which allows the dastardly virus to enter. In Crohn’s case, he was missing small bits of DNA that make the protein amenable to HIV. It was later discovered that around one percent of people of European descent carry two copies of this particular mutation and four to 15 percent with just one copy.

Both Timothy Ray Brown, Adam Castillejo (who received a stem cell transplant in 2016 and is considered the second person to be cured), a 66-year-old individual in California, and the Düsseldorf patient all received their bone marrow from donors with the CCR-delta 32 mutation.

All of these individuals, who initially underwent the procedure to treat leukemia, remained on their antiretroviral therapy for some number of years. They were deemed “cured” after blood tests found no traces of the virus or virus-infected immune cells in their bodies.

Can this cure everyone with HIV?

Again, all of the people currently treated with this method had leukemia and underwent a bone marrow transplant in an attempt to cure their cancer. And, unfortunately, this treatment is unlikely to be used for HIV patients who don’t have cancer. Bone marrow transplants are a risky procedure — like most organ transplants, you need to find a good genetic match, and even after surgical risks, there’s the risk of the new tissue being rejected (developing a condition called graft-versus-host disease) and other infections.

However, swapping out stem cells doesn’t necessarily have to be through the bone marrow. In 2022, a middle-aged woman of mixed race with leukemia became the first person to be cured of HIV by receiving a cord blood transplant in 2017. (Cord blood is the blood left over from the umbilical cord and placenta after the baby is born.) Stem cells from this transplant also contained the coveted CCR-delta 32 mutation.

It’s believed cord blood may have an advantage over bone marrow since it doesn’t require a close match, Yvonne Bryson, the chief of pediatric infectious diseases at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, who led the research told Inverse back in 2022.

The researchers of the Nature Medicine study acknowledge that, at the present, using bone marrow transplants is “neither a low-risk nor an easily scalable procedure,” but it’s at least another tool in our ongoing fight against HIV.

This article was originally published on