Operating Room "Spies" Reveal How Surgeons Wield Power, Rank, and Gender

"You. Me. Parking lot!"

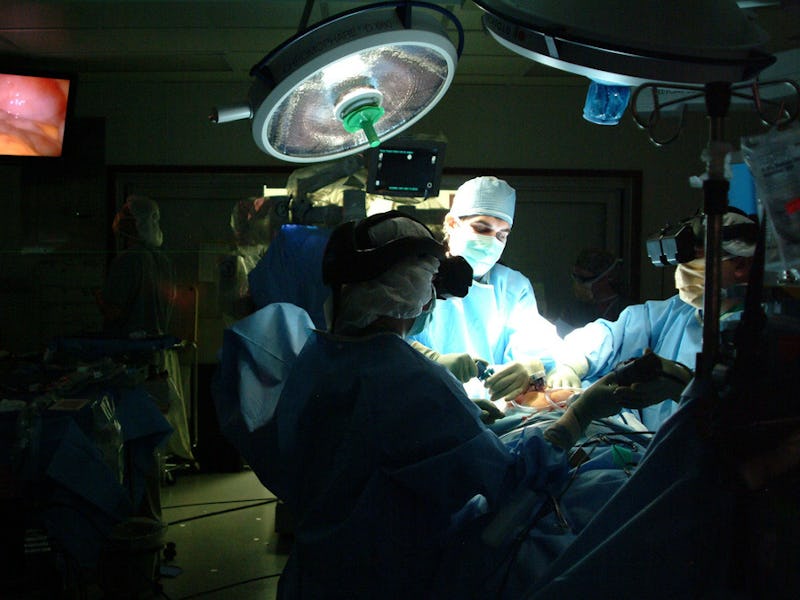

On Monday, psychologists at Emory University published a paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that should make Shonda Rhimes worry about her job security. As flies on the walls of 200 operating rooms over two years, they made some alarming discoveries about the dark side of power and hierarchy among surgeons, as well as some wonderful observations about how men and women work together.

The study was meant to investigate the types of social interactions that cause conflict in operating rooms. After all, fighting surgeons can’t be great for patient safety, so figuring out how to reduce conflict between them is an important part of healthcare. To do so, the team decided to determine how conflict arose in the first place.

“We decided we were going to look at the root: In an operating room, where all of the conflict kind of started,” first author and Emory University medical anthropologist Laura Jones, Ph.D., tells Inverse. Armed with recordings of all the interactions that went on during 200 operating procedures and a tool used by primatologists to study interactions between animals, Jones and her team got to work.

If the following real-life interaction, observed during the course of this study and summarized here, is any indication, it looks like the conflicts in operating rooms can get pretty serious indeed.

The attending surgeon and the anesthesiologist are huddled together watching a smartphone video. Simultaneously, the fellow is performing an operation and remarks, “Be careful, he might stick you [with a needle].” General chaos ensues, culminating with the fellow shouting “You. Me. Parking lot!” before he is calmed down by the attending surgeon.

Another example from the study describes how a surgical team briefly thought they had misplaced a needle. They searched the operating room for over 20 minutes before blaming the incident on a scrub technician who wasn’t even in the room at the time:

The attending surgeon shouted for answers, and the circulating nurse blamed an absent scrub tech… X-rays were ordered to make sure that the needle was not in the patient’s chest… Once a radiologist confirmed that she could not see a needle, the procedure resumed. The atmosphere in the room remained negative for the duration of the case, which ended an hour late.

Over the 6,348 spontaneous social interactions and “nontechnical communications” that the team logged, they found that only 2.8 percent rose to the level of “conflict.” It wasn’t just lost needles and near-fights in parking lots, however. The analysis, encouragingly, showed a great deal of cooperative behavior, with cooperative sequences observed 59 percent of the time.

Nurses, Jones says, often gave compliments to members of the surgical team that she notes helped improve performance and morale.

Determining patterns in social interactions was done using a method borrowed from primatologists called an “ethogram,” a type of shorthand that encodes behavior using letters and numbers to figure out “who does what to whom,” according to Jones. For example, if a nurse compliments an anesthesia provider, it would be coded as n (for nurse), f1 (for friendly; a hug or “very friendly behavior” might even be an f2 or f3), and a for anesthesia provider. Badmouthing the absent scrub tech might be considered an m1, or “mudslinging.” Putting time stamps on each one of these strings of codes made it possible to analyze them for patterns.

Some examples of codes the researchers used to construct their "ethograms."

Further analysis showed that four out of five conflict behaviors started with individuals who were several “ranks apart” in the hierarchy of the operating room (for instance, between an attending surgeon and a “scrub person”), notes Jones. She also points out that conflict behavior depends a lot on the gender breakdown of the group: Conflict was twice as likely to happen if a male attending surgeon was surrounded by other men compared to mostly women, and vice versa.

Taken together, these findings outline a good place to start for any healthcare institution looking to improve relationships between staff to better patient care. “Mixed-sex teams get along better,” Jones says. “There’s less competition for mates or status amongst people of the same gender. It was nice to get some data on that that’s not anecdotal,” she concludes.