This surprising new game wants to fix the worst thing about Risk

Inspired by Caribbean history and Hamilton, Liberation-Haiti is pioneering a different type of tabletop game.

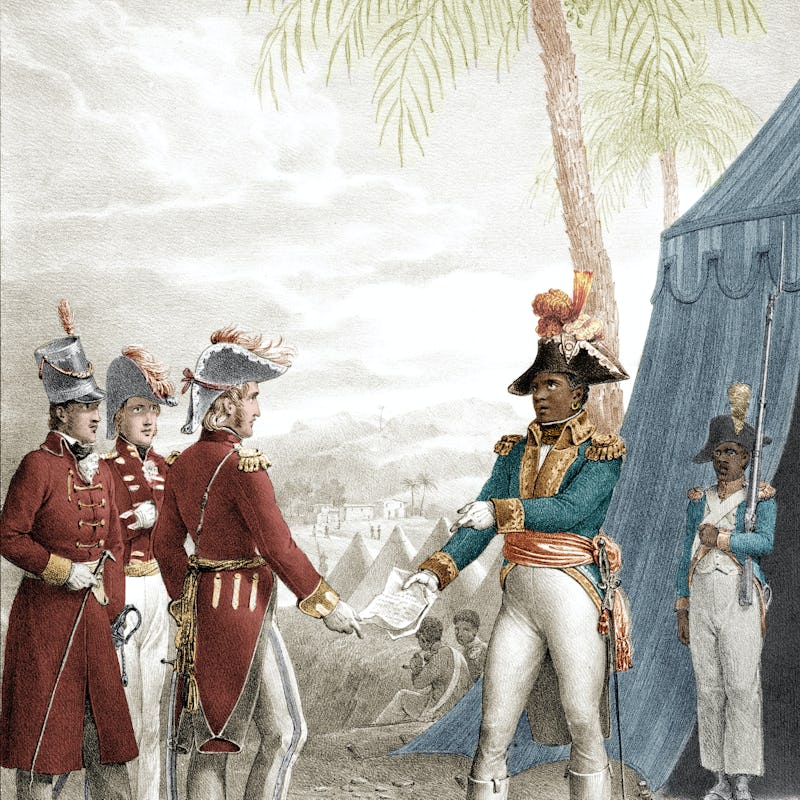

In 1803, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, a Black man from the Caribbean who was born into slavery, defeated one of the most powerful world leaders ever known: Napoleon Bonaparte.

Outmaneouvering the great general, Dessalines forced Napoleon’s army out of the French colony of Saint-Domingue and established himself as the de facto ruler of a new, free state of Haiti.

Some 200 years later, game creator Damon Stone is facing an almost equally formidable challenge. His goal? Translate Dessalines’s incredible victory over the French into Liberation-Haiti, the anti-colonialist answer to dominant board games like Risk and Settlers of Catan.

“I didn’t want anybody to have to play any aspect of the French.”

Stone isn’t the first person to challenge the built-in politics of most board games, but with years of experience and an industry award, he might just succeed. It also doesn’t hurt that the story of Haiti translates perfectly to the world of battle strategy games.

“The meaning of the Haitian Revolution is people fighting for a better way of life, sometimes disagreeing, but in the end succeeding at being the first country in the Western Hemisphere to leave slavery behind,” Stone tells Inverse.

But whether Liberation-Haiti is the start of a gaming revolution or itself a footnote in tabletop history depends on whether Stone can convince players and game-makers to play it at all.

“I didn’t want anybody to be colonists or slave owners and actively fight against abolition.”

Set between 1791 (when the first attacks on plantations began) and 1794 (when the French declared the abolition of slavery in Haiti), Liberation-Haiti is a faction-driven deck-builder and military game for 1 to 4 players. (In deck-building games, collecting the cards required for play is a core element of the gameplay itself.)

The first three factions — enslaved people, free people of color, and mixed-race Haitians all fighting against the French colonial government — correspond to different provinces of Haiti. The fourth player, the Maroons, represents escaped slaves living in remote mountainous areas across the map. Importantly, no one plays as the slave owners

“I didn’t want anybody to have to play any aspect of the French,” Stone says. “I didn’t want anybody to be colonists or slave owners and actively fight against abolition.”

“What American audiences really like to do is put Haiti in a box.”

That story of Haiti’s revolution lent itself so naturally to the mechanics of a cooperative board game that Stone was surprised no one had done it before.

“Once I decided this would be a cooperative game, it became very simple to turn out,” he says. “That makes it more depressing for me that there are so very few of them.”

Stone notes that, for much of the world, Haiti’s existence tends only to be acknowledged “when there is a disaster or national tragedy that may or may not impact a country that is not Haiti.”

Stone sees Liberation-Haiti as an opportunity to set the record straight on both the realities of slavery and Haiti itself, which he says only gets acknowledged by the rest of the world “when there is a disaster or national tragedy.”

“Flattening Haiti”

Concept art for the completed setup of Liberation-Haiti.

It’s indisputable that Haiti gets little attention in news and media in the United States, or that when it does, it’s frequently blamed or demonized as “dystopian” or “a basket case.” Robert Taber, assistant professor of history at Fayetteville State University and author of the upcoming The Haitian Revolution and the Making of the Modern World, tells Inverse that the country rarely gets the attention it deserves.

“What American audiences really like to do is put Haiti in a box,” Taber says, acknowledging a tendency even among historians for “flattening Haiti this way, making it a very simple, two-dimensional story.”

That flattening applies to the Haitian Revolution, which is still poorly understood in the United States. Back in 2010, televangelist Pat Robertson told viewers that, in the 18th century, Haitians had made a literal pact with the devil in order to win their independence from France. Today, schools barely mention the revolution outside of specialized courses in Caribbean history or colonial studies. Even in the 18th and 19th centuries, American and European media tended to diminish the significance of the revolution by reducing it to nothing more than a violent uprising.

In 1793, Haiti became the first country to permanently ban slavery.

That undermining of the Haitian struggle has long shaped the popular view of Haiti in the U.S., and those assumptions kicked into a higher gear in the mid-1910s when the U.S occupied Haiti.

“For the most part, the U.S. Marines are either coming from the Jim Crow South or the segregated North, and they came back with these stories and lurid tales of what they perceive as being Haitian Vodou, and zombies, and magical apparitions,” Taber says.

That image has persisted, and the Haiti half of Hispaniola has been persistently exoticized and depicted as fundamentally other: poor, superstitious, unfamiliar, and dysfunctional. Even among those sympathetic to Haiti, it’s rarely portrayed as complex.

Board games and colonialism

“I wanted you to have to take the cards that you had built and then use them to fight the revolution.”

As for the depiction of the Caribbean in board games, well, it’s frequently neither sensitive nor accurate. The popular tabletop game Puerto Rico — the number one ranked game on BoardGameGeek for much of the George W. Bush administration — is an especially egregious example. Players compete to colonize the island of Puerto Rico for the Spanish Empire. To build infrastructure and ensure profitable plantations, they rely on “colonists” represented by little brown tokens. This kind of depiction downplays that slavery was fundamental to the creation of European empires, especially in the Caribbean, and erases the violence of that history.

Some games do reject this trend. Spirit Island asks players to assume the role of a guardian spirit to drive out colonizers. Relatively few, however, push us to step into the past with a critical mindset.

Puerto Rico and its colonialist assumptions exemplify at least one generation of hobby board game design and tastes. So how did Stone, an Atlanta-based dance instructor and game designer who spent six years working at leading board game publisher Fantasy Flight come to make a game about the Haitian revolution? The answer is The Zenobia Award, a new contest offering underrepresented groups designing games about historical subjects a cash prize, mentorship opportunities, and assistance getting a game published.

After ranking as one eight finalists out of 150 entries, Stone is currently talking to publishers about releasing the game, but he never thought he’d make a game about history, revolutionary or otherwise. “That’s not my niche,” Stone says.

Making Liberation: Haiti

Concept art for Liberation-Haiti.

Stone grew up on Dungeons & Dragons and his preference has always been “American-style, thematic, immersive games,” especially expandable card games. Then, something changed.

“I was watching Hamilton for the third, fifth time, and the idea that people were learning about this particular period of American history because it was made in a very accessible format was just something I was fascinated by,” he says.

“I thought it would be fascinating to display the only successful slave uprising that resulted in the abolition of slavery for its people as well as the formation of a country in which the revolutionaries were still in charge.”

“I was watching Hamilton for the third, fifth time.”

As part of the Zenobia Award process, Stone worked with historians to capture the feeling and flavor of history. What he came up with is a card-driven wargame whose gameplay is split into two distinct halves. The first is a deck-building game where players amass cards they will use as resources once the fighting begins. From there, though, Liberation-Haiti diverges from the deck-builder formula.

“I wanted you to have to take the cards that you had built and then use them to fight the revolution,” Stone says, “deploying units and assigning different personages and equipment, moving around the map, fighting off enemy forces, and laying siege.”

The full complexity of history can’t fit into the rules of a game that plays quickly, so some elements like factional rivalries had to be cut. Others, like alliances of convenience with Spanish and British troops, had to be simplified.

“They obviously didn’t really care about the abolition of slavery,” Stone says, “but what they were pro was France getting its comeuppance.”

Concept art for Liberation-Haiti.

Stone focused on capturing what experts call the “historicity,” or the feeling of historical accuracy of the struggle. Players even meet Haitian leaders, ranging from military commanders like André Rigaud to figures from the emerging Voodoun religion and military genius Toussaint Louverture, whose card offers a welcome boost to a faction’s morale.

Making Liberation-Haiti fully cooperative also demanded some historical abstraction. The reality of the war found infighting between revolutionaries.

“There was no one clean moment where this happened and all the people of color rose up and fought for abolition,” he says. “It’s a bloody, confusing war where everybody sides with everybody else, except for the slaveholders.”